Galernaya St., 58-60, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190121

It is known that in the second half of the 18th century, the estate on this site was owned by the cabinet secretary A.V. Khrapovitsky. The nearby Khrapovitsky Bridge over the Moika River was named after him.

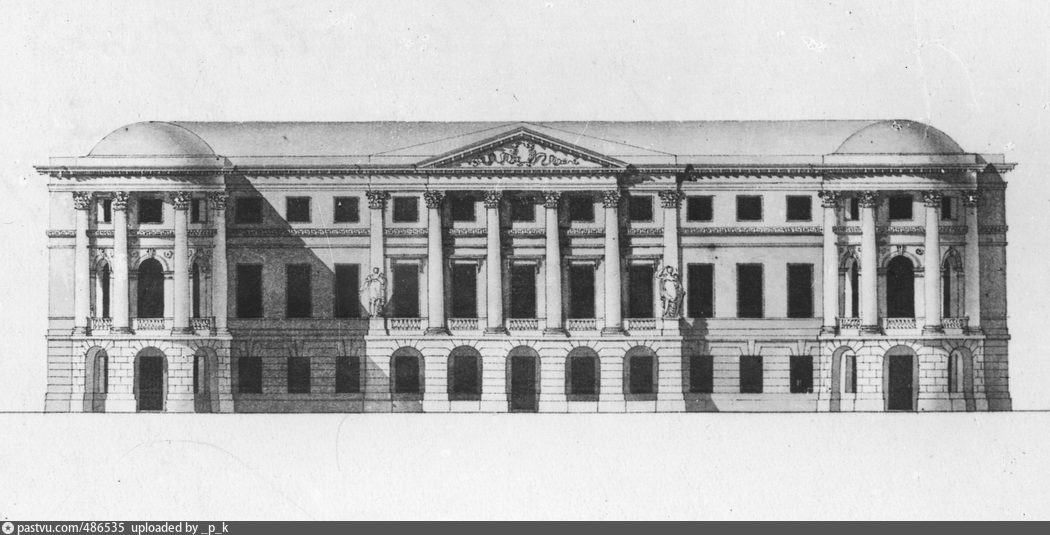

On the plan by Pierre Antoine Saint-Hilaire (1765–1773), the palace, wooden embankments of both canals, the bridge, and the garden were already marked. At that time, the garden was formal with small saplings, enclosed by a wooden fence. In 1790, the building was purchased by the well-known senator Pyotr Vasilyevich Myatlev, for whom it was rebuilt by the Italian architect Luigi Rusca. Luigi Rusca remodeled the old structure and erected a large house at the corner of the two canals, with the main facade facing Galernaya Street and the second facade facing the garden, towards the Moika and Admiralty Canal. The palace is located in one of the oldest districts of the city, which was already considered quite prestigious by the end of the 18th century.

In 1790, the building was purchased by the well-known senator Pyotr Vasilyevich Myatlev, for whom it was rebuilt by the Italian architect Luigi Rusca. This was the first independent work of the architect, a major representative of neoclassicism, who later became a court architect. The appearance of the palace has not undergone significant changes since then. In 1796, another building (No. 60) joined the complex on Galernaya Street — the former house of architect Savva Chevakinsky.

The love story of Catherine the Great and Grigory Orlov is widely known, as is the fact that Catherine bore a son by Orlov. The baby was born secretly in the Winter Palace. Somehow, Catherine managed to conceal her pregnancy. Incredible but true — her husband, Emperor Peter III, remained unaware, or perhaps he knew but did not care. The boy was entrusted to Catherine’s wardrobe master Vasily Shkurin, who raised him as his own son (he had his own sons as well).

The progenitor of the family was Alexey Grigorievich Bobrinsky (1762–1813).

After the completion of the palace construction in 1797, P.V. Myatlev immediately sold the building. There is evidence that the palace was acquired by the Empress’s favorite Platon Zubov. Empress Maria Feodorovna then purchased the palace from him. However, it is possible that the Empress bought the palace directly from Myatlev, who never intended to live there and carried out the construction work at the request of the imperial family. Maria Feodorovna, immediately after the purchase, gifted the palace to Count A.G. Bobrinsky in gratitude for his gratuitous transfer of his previous house on the Moika (house 50) to the Foundling Home for its expansion.

The love story of Catherine the Great and Grigory Orlov is widely known, as is the fact that Catherine bore a son by Orlov. The baby was born secretly in the Winter Palace. Somehow, Catherine managed to conceal her pregnancy. Incredible but true — her husband, Emperor Peter III, remained unaware, or perhaps he knew but did not care. The boy was entrusted to Catherine’s wardrobe master Vasily Shkurin, who raised him as his own son (he had his own sons as well). Alexey Grigorievich Bobrinsky was recognized by Paul I, who called him “brother,” elevated him to count, appointed him major general, honorary guardian, and manager of the St. Petersburg Foundling Home.

In the 19th century, the palace was one of the most famous centers of social and cultural life in St. Petersburg. The salon of the Bobrinsky countesses attracted diplomats and writers; it was visited by Emperors Alexander I and Nicholas I, and “the whole capital” danced at the balls. Anna Vladimirovna Bobrinskaya, the count’s wife, née Baroness Ungern-Sternberg, expanded the palace, decorated its interiors in the latest fashion, and founded a salon frequently attended by Emperor Nicholas I and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. The salon of the younger Countess Bobrinskaya was gladly visited by Vyazemsky and Zhukovsky (in 1819 he was infatuated with her and dedicated several of his works to her), the Vielgorsky brothers, and Chancellor Gorchakov. Pushkin regularly visited the palace. In Pushkin’s diary for 1833–35, it is mentioned that he attended lunches at the Bobrinskys’ (specifically on December 6, 1833, and February 28, 1834), and on January 17, 1834 (January 1, 1834, by the old style, when he was granted the rank of chamberlain), he attended a ball at the palace and left the following note:

“Ball at Count Bobrinsky’s, one of the most brilliant. The sovereign did not speak to me about my chamberlainship, and I did not thank him. Speaking about my ‘Pugachev,’ he said to me: ‘It’s a pity I did not know you were writing about him; I would have introduced you to his sister, who died three weeks ago in the Erlingshof Fortress’ (since 1774!). True, she lived freely in the suburbs, but far from her Don stanitsa, on a foreign, cold side. The Empress asked me where I traveled in the summer. Learning that it was Orenburg, she inquired about Perovsky with great kindness.”

“Natasha’s presentation at court was a huge success — everyone is talking about her. At the ball at the Bobrinskys’, the Emperor danced with her, and at dinner he sat next to her.”

The salon of the countess also received the poet’s adversaries: Count Nesselrode, Baron Hecker, Georges d’Anthès.

Count Alexey Alekseevich was one of the founders of the joint-stock company for the construction of the Tsarskoye Selo Railway. In 1835, to attract additional funds to the company’s capital and to convince skeptics of the railway’s technical feasibility, he built a section of railway in the palace garden, on which a cart loaded with 500 poods of stones moved.

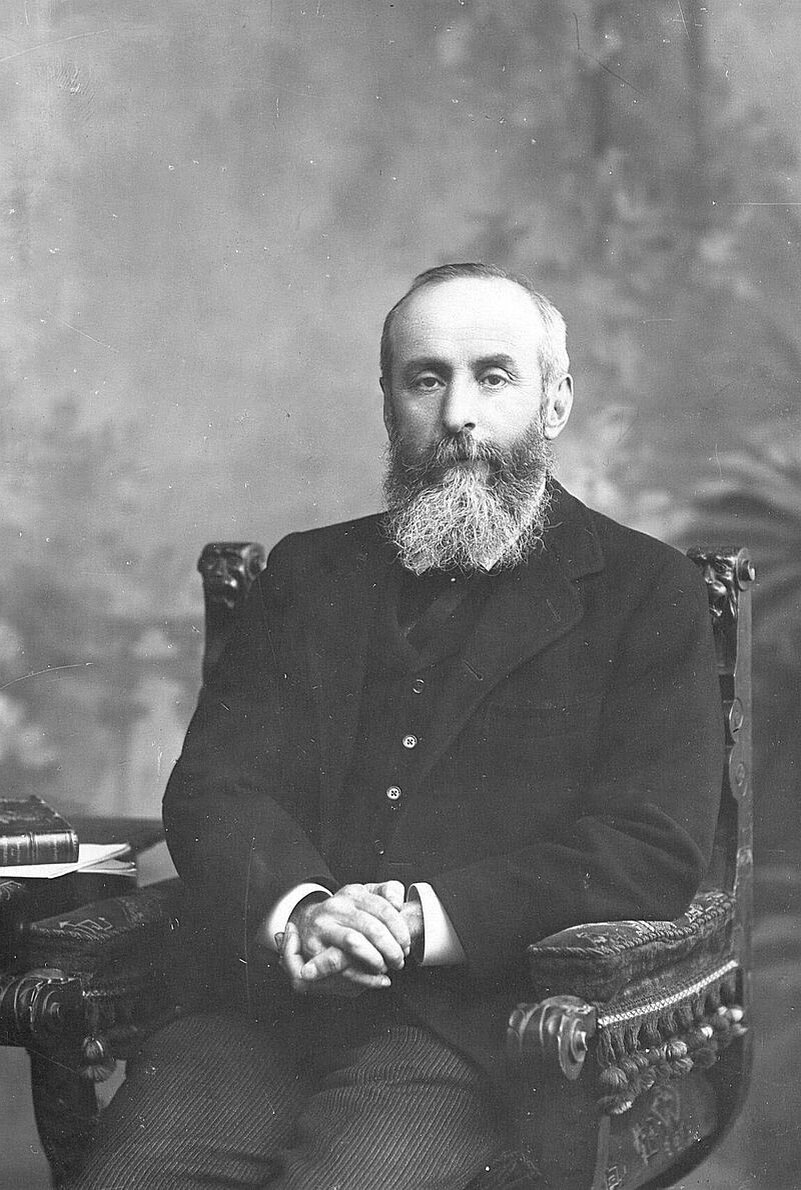

The last owner of the estate from the Bobrinsky family was Count Alexey Alexandrovich Bobrinsky, a historian, archaeologist, senator, leader of the nobility of the St. Petersburg Duma, vice-president of the Academy of Arts, and from 1896 chairman of the Archaeological Commission.

During World War I, he donated his palace free of charge for use as a Red Cross hospital. Then, in 1917, it was used as barracks for women’s and Latvian battalions. At that time, Bobrinsky no longer had funds to maintain the palace — all his bank accounts were frozen. Attempts to obtain funds for the hospital’s maintenance were unsuccessful.

At that time, the palaces of St. Petersburg began to attract the attention of thieves and robbers... The country was in disorder and chaos, leading to food shortages. Rumors spread that the former owners, who had already fled to Europe, had hidden treasures in the palaces. Also, the wine cellars attracted crowds...

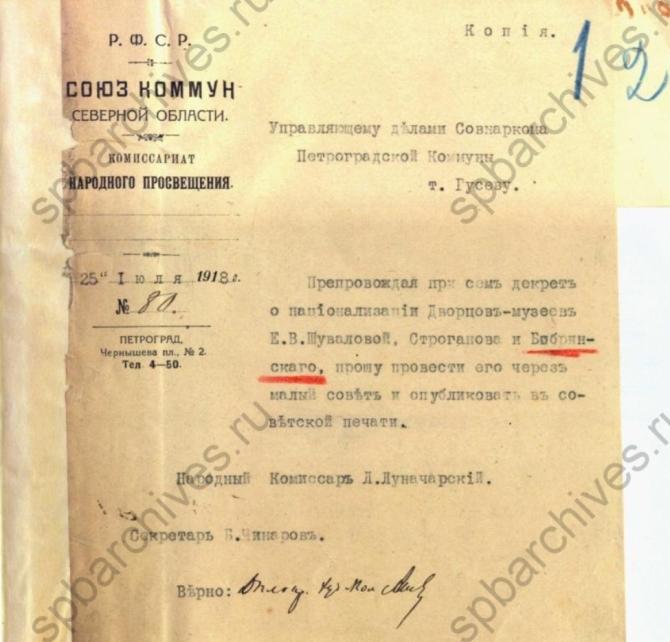

The Bobrinsky Palace was saved from looting by a decree that nationalized it along with the Stroganov and Shuvalov palaces.

After this happened, the owner Alexey Bobrinsky left for southern Russia, then Kyiv, from there to Constantinople, and further to France, where he died. Alexey Alexandrovich left Russia in haste, practically fleeing. It is assumed that he hid the jewels in a secret place somewhere near his palace. The continuation of the story is that in 1930, the Leningrad GPU received a letter from a certain Bobrinsky in France, who offered the Soviet government a deal. The essence was that he indicated the location of the treasure with Catherine the Great’s jewels! Bobrinsky demanded half the value of the treasure.

In the 1920s, the building housed the Historical and Everyday Life Department of the Russian Museum. In 1925, an exhibition “Merchant Portraits of the 18th–20th Centuries” was organized here, with a partial “recreation” of historical-typological interiors, including a fanciful “Merchant’s Parlor of the 1840s–50s.”

Subsequently, the collection of paintings gathered by the Bobrinskys, furniture items (including the set from the Red Drawing Room) were transferred to the State Hermitage. The palace library of more than 13,000 volumes was distributed among museums and libraries. The rich decoration of the palace was partially looted and partially transferred to various museums across the country. For example, some items from Bobrinsky’s art collection ended up in the Nalchik Regional Museum. Also, since 1929, the building housed the Central Geographical Museum, created by V.P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky. The museum organized thematic exhibitions seen by tens of thousands of people. In early 1933, a USSR Gosplan document even declared the museum “shock.” All Leningrad schoolchildren and many foreign visitors passed through the museum. In 1931, the museum was compressed, giving 1,500 square meters to the “Giprovod” organization. Due to “Giprovod’s” mismanagement, a fire broke out in the building in summer 1931, damaging the museum’s local history department. Then the “Giprovod” premises were given to new tenants. Only in 1935, after a new law on museum protection was passed in 1934, was the entire building returned to the museum. But with Semenov-Tyan-Shansky’s resignation due to health, the museum began to decline. When the museum was eventually transferred to Leningrad University, the museum space was first occupied by the university’s correspondence department, then by a vocational school. In early 1941, the Leningrad City Council and Leningrad State University rectorate issued a decree to close the museum.

In 1952, the palace housed the Geography Faculty of Leningrad State University, and from the 1960s — the Research Institute of Complex Social Research (NIIKSI) and the Psychology Faculty of Leningrad State University. No comprehensive restoration of the palace was carried out during the Soviet era; the premises (including the palace halls) gradually fell into disrepair.

From the memoirs of a student (1968–1973) of the Psychology Faculty of Leningrad State University, L.V. Bochishcheva:

“I also really liked this old house — the central staircase with a huge mirror on the side, the beautiful old chandeliers, and the wooden spiral servant staircases, which we used to climb from the second to the third floor, under the roof, where there were small rooms that apparently once housed servants. In our time, they were used for seminars and foreign language classes, and beyond were laboratory rooms. But it must be said about the terrible condition of the building: in the third year, during a lecture in the chamber hall, a large piece of stucco fell with a crash onto the Vietnamese students sitting by that wall. Fortunately, they reacted quickly — jumped back, ducked, and were only dusted. They were not very scared because they were at war and were used to such surprises.”

From the memoirs of sociologist E.E. Smirnova:

“The interaction between NIIKSI and the Psychology Faculty was a special chapter in the institute’s life. Both organizations were located in the Bobrinsky Palace on Krasnaya Street (now again Galernaya) in the 1970s. This mansion deserves at least a brief description. At that time, only a few rooms retained traces of former splendor. The small oval director’s office faced the garden with tall trees through its high windows, and in spring, blooming chestnuts were visible. It still had bookcases. The ceiling was painted with small stars. Many department heads admitted that during boring meetings they tried to count them. The noble proportions and coziness of this office impressed almost everyone. The legal laboratory was located in the Red Drawing Room (our local name). It retained dark red silk on the walls, mirrors, and gilding. Two other laboratories — sociological and Lisovsky’s laboratory — preserved only a little stucco. Almost all other rooms had a simple working appearance, with walls painted in oil paint. At that time, several rooms still had unique bronze chandeliers. The building had a U-shaped layout. The faculty occupied one wing, NIIKSI was in the central part, and the other wing was given to a clinic. The wings had rooms on the first floor with windows at sidewalk level, making work difficult due to periodic rat invasions. Our laboratory had to endure this for several years, so we were familiar with these problems.”

On December 13, 2001, the Federal Commission for State Property Management transferred the Bobrinsky Palace to the jurisdiction of St. Petersburg State University. Since 2002, the palace premises have been used for classes by the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Since 2003, urgent repair and restoration work began, as several rooms were at risk of wall collapse. The reconstruction project provided for preserving the facades, roof configuration, vaulted ceilings of the first floor, as well as restoring the surviving decorative finishes of the main rooms, metal and brick fences. The main building’s ceremonial rooms were adapted for library reading rooms, a conference center, and several large lecture halls. Restoration lasted about eight years. The grand reopening of the Bobrinsky Palace after restoration took place on August 31, 2011.

Also, since 2016, tours (by prior arrangement) have been periodically held in the palace as part of the “Open City” project.

Sources:

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_of_the_Bobrinskys

https://adresaspb.com/category/structures/building/arkhitektor-rafael-dayanov-dvorets-bobrinskikh/

Millionnaya St., 9, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

1st Elagin Bridge, 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197183

Millionnaya St., 5/1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Palace Embankment, 26, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

English Embankment, 54, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

2 Maksim Gorky Street, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198515

Universitetskaya Embankment, 15, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

Fontanka River Embankment, 25, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

4 Inzhenernaya St., Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Building A, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Isaakievskaya Square, 6, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190107

Nevsky Ave., 39, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

Fontanka River Embankment, 34, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191014

Nevsky Ave., 5m, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Moika River Embankment, 122, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190121

Palace Embankment, 18, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Embankment of the Malaya Nevka River, 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197045

Moskovsky Ave., 9b, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190068

26 Sadovaya St., Building A, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

Shpalernaya St., 47, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191015