Oktyabrskaya Embankment, 72, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 193079

The history of constructions on the site of the park dates back to the period of Swedish rule. A village was located on the site of the estate, surrounded by several brick factories that operated for a very long time—until the beginning of the 20th century. The bricks from these factories were used to build the Swedish town of Nien, which preceded St. Petersburg. Besides working at the brick factories, the local residents engaged in fishing. After the victory in the Great Northern War, the village received the Russian name Gleznevo.

Peter's decree of 1716 sent fishermen from the Oka River to permanently settle in the village; they supplied fish to the tsar’s table. The village’s name was changed to Rybatskoye (Fishermen’s). Later, when some fishermen moved to the left bank because it was more convenient to reach the markets in the city center due to the lack of bridges, the village became known as Maloye Rybatskoye (Little Fishermen’s), and the relocated fishermen formed a settlement that later developed into the Rybatskoye district. Fishing opportunities remain to this day, and during the smelt run, a temporary fishing pier is installed on the embankment directly opposite the estate on the Neva River. On the 1817 map, the village of Maloye Rybatskoye is still visible on the site of the estate. In 2022, the toponymic commission of Saint Petersburg restored the name of the microdistrict around Sosnovka to its historical name "Maloye Rybatskoye," as one of the oldest districts of the city.

Prince Gavriil Gagarin was the client of the park in its current concept of landscaped ponds and a garden on the embankment.

Plan of Prince Gagarin’s estate in 1824. The layout of Chernov’s garden during restoration was made close to this map. The pond system in Prince Gagarin’s estate was about twice the size of the current one. Around 1820, the owner of the land with the pine forest became Prince Gavriil Petrovich Gagarin, known as a minister, writer, and representative of Freemasonry in Russia. He built a wooden manor house on the estate. On the 1824 map, it can be seen that Gagarin’s estate already had a park and a pond system created by order of the prince. The garden adjacent to the Neva still largely repeats the layout of paths and planting schemes of Gagarin’s early 19th-century estate. This is due to the 2007 reconstruction, which was based on old maps. The luxurious and huge park for the early 19th century reflected the status of the prince, who traced his lineage back to Vsevolod Yuryevich "Big Nest"—the Grand Prince of Vladimir. However, the estate was used by his son Pavel Gavrilovich Gagarin, known as a brilliant diplomat, military man, and writer. Nevertheless, the estate bears witness to the drama of his personal life. The prince’s first wife was Anna Lopukhina, a lady-in-waiting to Empress Maria Feodorovna. However, she became the favorite of Emperor Paul I, which gave the prince a rapid career rise but an unhappy family. Prince Pavel was forced to move completely to Sosnovka at age 54 after his second marriage to ballerina Maria Spiridonova. The couple was happy, but the high society of St. Petersburg considered marriage to a "commoner" unacceptable for a descendant of Rurik. Therefore, the prince left the family mansion on the Palace Embankment and secluded himself in the estate near the pine forest. Prince Pavel was so in love with his chosen one that he even renamed the Sosnovka estate to Maryino, which can be seen on some 19th-century maps.

After the prince’s death, the estate was sold several times until 1889, when it was purchased by Colonel Alexander Ivanovich Chernov. Chernov planned to build a luxurious stone mansion for himself and demolish the old wooden house of Prince Gagarin.

Although he later attained the rank of general, even historians are unclear about the details of his military career and achievements. Chernov became known not as a military man but as a land businessman and charismatic personality prone to adventurous projects. He came from the wealthy Chernov family, whose coat of arms still decorates the doors of the estate today. The merchant Chernov family was ennobled only in 1838 as a reward for supplying Russian troops during wars. Wanting to maximize income from Sosnovka, Chernov decided to sell part of the land for an agricultural colony. He actively collected advance payments for a yet non-existent settlement, in which a "Chernovsky Prospect" was already planned. However, Chernov allocated swampy plots for sale and received many complaints from buyers. Eventually, the zemstvo forbade him from engaging in "land development" without proper land preparation and obliged him to return deposits to some buyers. The plots cut by Chernov that he managed to sell are still visible on the 1935 map. Later, a hospital for war veterans was built on their site. General Chernov was also prone to a dissolute lifestyle, which is reflected in the architecture of the Sosnovka estate, where he demanded from the architects to connect his "office" directly with the wine cellar and bedroom. As one of the estate’s architects, A. V. Kuznetsov, wrote, the general demanded the office be designed "for special visits" in an "intimate setting." The general’s character, who walked around the house naked and kept horses like a tsar for hunting, draws attention to his lifestyle in Sosnovka. It is evident that General Chernov tried to get the maximum pleasure from life, even in old age participating in horse races and yacht competitions as a member of the Trotting Racing Society and the St. Petersburg Yacht Club.

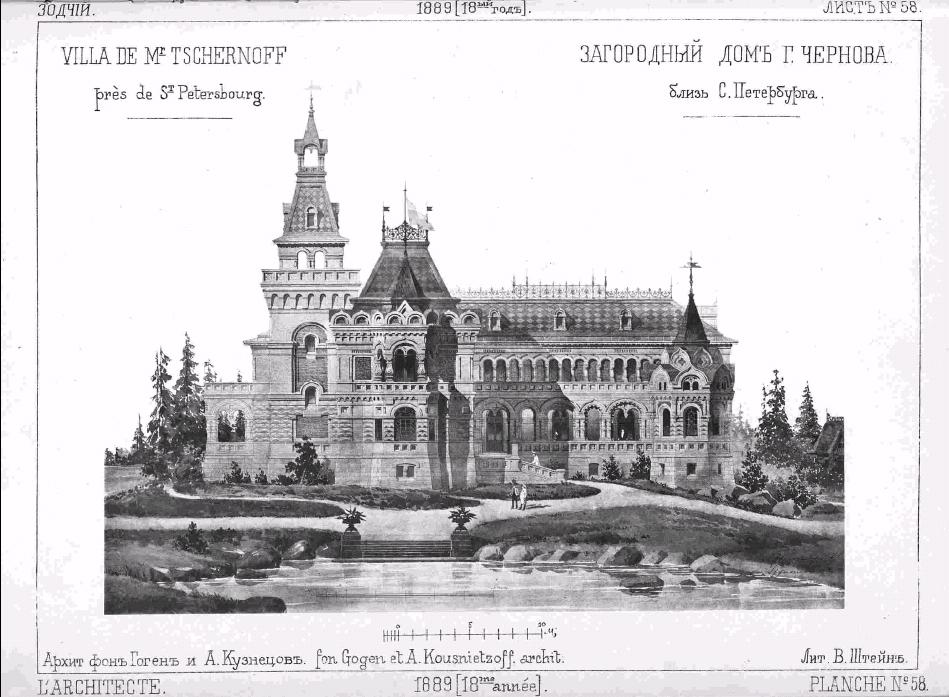

Chernov prepared a detailed brief for the architects on the mansion’s layout, considering his entertainments and planned guests. The architectural appearance of the new mansion’s exterior was designed by von Hogen in the Neo-Russian style but in a rather unusual free eclectic interpretation. Hogen used this variant of eclecticism inspired by Russian architecture only in one other work—the Suvorov Museum in St. Petersburg, which was built after Chernov’s dacha and became a source of his architectural solutions.

An essential attribute of the Neo-Russian style chosen by Hogen is the tented towers. Hogen placed them at different levels, giving the building dynamism. To enhance the effect, rich decor was used, including facade inserts with flower images. The basement floor was done in a European style close to medieval hunting castles. This reflects the character of the owner, who was an avid hunter. The mixing of styles allows us to say that the building is best classified as eclecticism based on a mixture of Russian and Western European traditions combined with the latest facade decoration methods of that time. The mansion’s facade includes rich decor and many viewing and walking platforms.

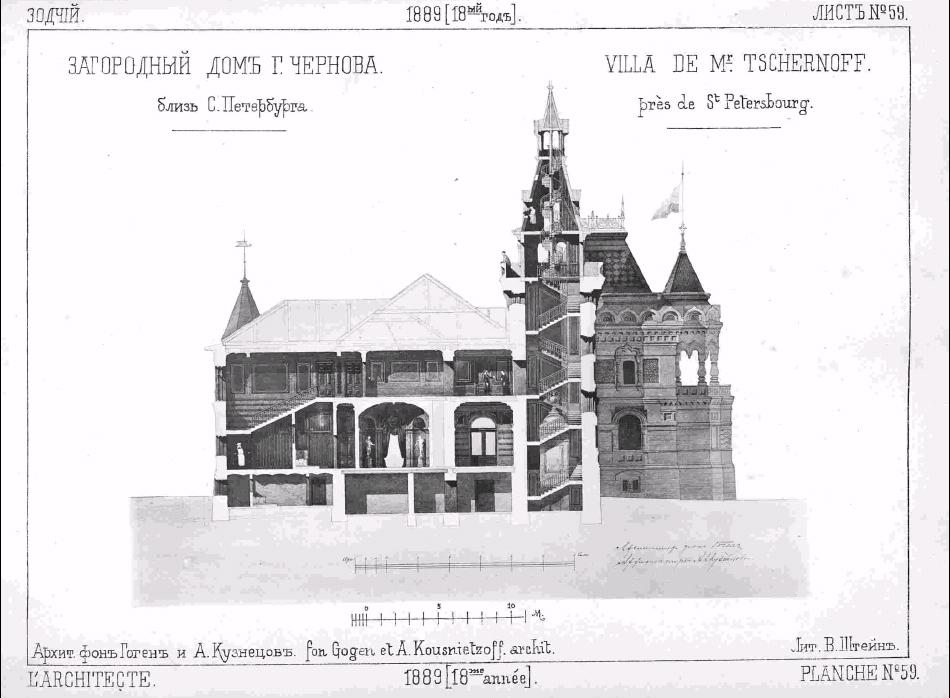

In issues 11-12 of "Zodchy" magazine in 1889, an article by architect A. V. Kuznetsov about the project was published.

Drawings signed by A. I. von Hogen and A. V. Kuznetsov were also published there. Below is a brief description of the mansion based on the architect’s article, but later reconstructions must be taken into account.

The mansion initially had a living area of 2,000 m² over 3 floors, consisting of 25 rooms divided into ceremonial rooms for guests, private rooms for the owner, and rooms for servants. However, Radio Center No. 3 carried out a reconstruction of the mansion to accommodate radio equipment and power substations. According to Rosreestr data, the living area was reduced to 1,599 m². The remaining area is occupied by equipment. Additionally, the number of floors increased from 3 to 4. The original project included a very large, unheated attic, which was not intended for use as a room. The radio center used the attic to house communication equipment and installed a parabolic antenna on the mansion’s roof. To accommodate power substations for radio equipment, an extension was built on the front facade with air cooling through ventilation openings. Some equipment was also placed in the basement, also equipped with air cooling.

Most of the layout solutions were devised by Chernov himself as a brief for the architects; the building’s facade was implemented by the architects at their discretion.

The estate’s estimate, excluding room finishing and landscaping work in the park, amounted to 88,072 rubles. Since the gold standard for the ruble soon came into effect, the equivalent cost of the estate building was more than 100 kilograms of gold coins at the exchange rate of that time.

The basement (ground) floor is residential with a ceiling height of 284 cm. The upper part of the basement floor is raised halfway above ground level to provide natural lighting through windows. There was a spacious kitchen and several rooms for household servants, connected to the first floor by a separate servant’s staircase.

The architects actively used new technologies of the time, and the ceiling was supported by metal structures ("rails").

A highlight of the project was "Chernov’s office," which reflected his entertainments. The office was the central and largest room in the mansion. According to Chernov’s request, the office was to be designed as an intimate zone for "special visits," not for business receptions as was customary at the time. The "intimacy" of the office area meant that Chernov and his "special visitor" could use many important rooms without crossing paths with other guests or even servants in the house. The office had a separate entrance from the street through a porch with an adjoining gallery, allowing the general to bring a guest into the house through a separate intimate entrance. In fact, the mansion was divided into intimate and public parts.

The office is connected by a staircase enclosed within the tower walls to the wine cellar located below in the basement and to the bedroom located above the office on the second floor. Chernov deemed it necessary to complement the "workspace" not only with a wine cellar and bedroom but also with access from the office via a staircase to the second floor to a photographic pavilion. After the general, no photographs of his work with his "special visitors" remained, as he likely took them with him into emigration.

Access to Chernov’s office was only possible through the library, which was meant to give visitors the impression of the owner’s erudition, but as Kuznetsov ironically notes in his article, it was more a set of bookcases as decoration than a real library.

Between the turns of the staircase in the tower, a secret compartment was also arranged for storing valuables and documents.

On the first floor, there was a dining room adjoining a guest (ceremonial) hall. The idea was that the latter could also serve as a dining room during large gatherings. These rooms were connected by an arch, forming one space. Through the ceremonial entrance, one could enter the ceremonial hall via an octagonal living room or the billiard room.

The spacious billiard room on the first floor was designed to accommodate both a billiard table and sofas for guests. A passage through the gallery to the home church was planned, but the general ultimately abandoned the construction of the church.

Most of the interiors of the first-floor rooms have been well preserved in terms of windows, doors, and ceiling decoration. The ceremonial staircase has been preserved in its original form.

As noted, from the private staircase in the tower, the general and his guest could reach his bedroom and the room designated for the photo pavilion.

In the depth of the general’s spacious bedroom, there is an alcove with access to a restroom.

The long open terrace above the first-floor gallery overlooking the Neva was intended as a walking place only for the owner and his "special visitors," as it has an entrance only from his bedroom through a door in his private restroom. Also, access to the viewing balcony overlooking the Neva above the office is possible only from the general’s private bedroom. Three rooms were allocated for visiting guests. Two rooms were for the estate manager. All these rooms have separate exits to the wide platform of the ceremonial staircase.

When the mansion was converted into a hospital, most of the second-floor interiors were destroyed, but the original room layout and historic windows were preserved. The 21-meter-high tower is built of brick up to the roof’s base; above that, it is constructed from metal structures covered with wooden cladding, which is then covered with a metal roof. The tower houses a preserved cast-iron spiral staircase decorated with ornamental castings. The staircase leads to an observation deck with panoramic views of the surroundings. Chernov intended the observation deck to be higher than the crowns of even century-old trees so that guests could see to the horizon in all directions, which was meant to impress the general’s private guests. Access to the tower’s observation deck is also intimate, through the staircase in the tower adjoining the bedroom.

The dacha was built in just 3 years by 1893, and this year is reflected on the weather vane on its tower. Hogen, together with two assistants—then young but later also well-known architects A. I. Kuznetsov and G. I. Lyutsedarsky—carried out not only the dacha’s construction but also the park’s reconstruction and the shaping of the ponds to their modern state. The park quickly became popular in the area, so Chernov, by then a general, began charging an entrance fee of 2-5 kopecks. Besides the opportunity to relax, it turned out that the park and the adjoining pine forest provided good conditions for growing various mushrooms, and many visited Chernov’s estate as mushroom pickers. Mushrooms are still collected in Sosnovka’s territory today. The magazine "Capital and Estate" in 1915, issue No. 25, wrote that gazebos were built on islands in the ponds and that the huge park naturally transitioned into the pine forest.

In 1918, Chernov either emigrated from Russia or died due to his wild lifestyle. The circumstances of the general’s death are a subject of debate among historians. In any case, in 1918, the mansion was left ownerless.

In 1919, Chernov’s mansion was opened as a rest home for workers of the Nevskaya Zastava. However, the estate’s elite status made it effectively a dacha for the Leningrad House of Writers, where writers and poets could come upon recommendation. Many famous Soviet Russian writers rested at Chernov’s dacha. Visitors included Nikolai Gumilev, Erich Gollerbach, Nikolai Volkovsky, and many others. Gollerbach noted that when Gumilev read poetry at the dacha, a quite colorful society of workers, writers, and "bourgeois ladies" gathered to listen. Volkovsky wrote that at the dacha one could listen to Gumilev "without commissars, without slogans, without leather jackets and ‘party discipline.’"

In 1930, the rest home was closed, and a maternity hospital opened on the first floor, with a polyclinic on the second. In 1941, a military hospital was built nearby, and doctors moved to work there. Later, in 1946, it was repurposed into the now well-known Hospital for War Veterans.

Towers between which the antennas of Radio Center No. 3 were previously stretched

According to the decree of the Military Council of the Leningrad Front dated April 25, 1943, a radio station RV-1141 with a shortwave transmitter of 60 kW power was built on the former dacha’s territory, marking the start of Radio Center No. 3. On November 6, 1943, the radio station began broadcasting with a speech by Joseph Stalin. After the radio center was built, the dacha and its park became closed to visitors.

After the first few broadcasts, the station was heavily shelled, and the equipment had to be removed for storage. The station resumed broadcasting on June 20, 1944, after the lifting of the Siege of Leningrad.

According to Rosreestr data, construction of six "radio towers" was completed in 1949. The radio towers are 75 meters high. Various radio equipment was later installed on them.

Radio Center No. 3 was used to "jam" Western shortwave radio stations on Soviet territory. During the ideological confrontation of the two systems, it was necessary to drastically increase the power of broadcasting stations to effectively counteract capitalist bloc radio stations deployed along the USSR border. In the 1950s-1960s, radio centers around Leningrad were included in a program to deploy powerful electronic warfare transmitters. Several generations of jamming transmitters existed, such as "Sneg," "Typhoon," and "Buran." The "Buran" transmitter, with 500 kW power, was usually used in a "paired" configuration DS-1000 with about 1 megawatt power, classifying it as a super-powerful transmitter even today. "Buran" used innovative evaporative cooling of tubes. In 1963, a large garage of 515 m² was built near the estate for equipment installation and maintenance. The specific configuration of Radio Center No. 3’s electronic warfare equipment remains classified, but the standard deployment for Leningrad radio centers included several "Buran" units with a total power of about 2-4 megawatts. Such high power was required because NATO military stations for "Voice of America," "Radio Free Europe," "Radio Liberty," "BBC," and "Deutsche Welle" had 500 kW power but were deployed in multiples right at the USSR borders and could reach major cities like Leningrad in a single ionospheric reflection. To jam them over a large area of the USSR, an electronic warfare transmitter of at least 2-4 megawatts was needed.

To accommodate antennas for powerful transmitters, the radio towers were reconstructed into masts. The antennas themselves were stretched between the radio towers and were 100 meters long. A total of 32 such giant antennas were stretched between masts on two sites. During the Soviet era, the park territory was fenced with a concrete fence, alarm systems were installed, and militarized security posts were built. For security needs, most of Sosnovka’s territory was equipped with electric lighting. Due to high radiation from operating antennas, residential development adjacent to the radio center was prohibited.

After the USSR’s collapse, Radio Center No. 3 was used for medium-wave broadcasting for some time. Expensive copper antennas were cut from the towers and sold as valuable metal. The center continued broadcasting for the Orthodox Church’s Radonezh radio station. Before ceasing broadcasting, the radio center had 4 transmitters of 10 kW and three antennas. On September 20, 2016, broadcasting from Sosnovka was stopped, and the radio center’s equipment was dismantled and moved to Krasny Bor in the Tosnensky District.

Sources:

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Дача_Чернова

https://www.gov.spb.ru/gov/otrasl/c_govcontrol/news/238457/

https://www.citywalls.ru/house1410.html

Leuchtenberg Palace, Oranienbaum Highway, 2, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198504

72, Andrianovo, Leningrad Region, Russia, 187031

Museum-Estate of N.K. Roerich, house 15a, Izvara village, Leningrad region, Russia, 188414

CQX4+FJ 5th Mountain, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Estate Bridge, Kiev Highway, 106, Rozhdestveno, Leningrad Region, Russia, 188356

Mezhozyornaya St., 9, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 194362

Sverdlov Sanatorium, 2, Sverdlov Sanatorium, Leningrad Region, Russia, 198327

FQM3+M3 Verolantsy, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Gatchinskaya Mill, 2, Myza-Ivanovka, Leningrad Region, Russia, 188352

pr. Stachek, 3 92, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198096

Priyutinskaya St., 1, Vsevolozhsk, Leningrad Region, Russia, 188641

MX4P+HH Ananino, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Kotly, 96, Kotly, Leningrad Region, Russia, 188467

Institutskaya St., 1, Belogorka, Leningrad Region, Russia, 188338

74V2+W3 Mars, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Fontanka River Embankment, 118, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190068

Nagornaya St., 47, Gostilitsy, Leningrad Region, Russia, 188520

Stachek Ave, 226, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198262

Pesochnoe Highway, 14, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 194362

Bolshaya Alley, 13, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

nab. Krestovka River, 10, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197110

Polevaya Alley, 8, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Teatralnaya Alley, 3, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Primorskoe Highway, 570L, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197720

Primorskoe Highway, 566, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199004

Side Alley, 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Embankment of the Malaya Nevka River, 25, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Primorskoe Highway, 690, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197729

MM7J+CP Sokolinskoye, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Side Alley, 11, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Bolshaya Alley, 12, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

13 Akademika Pavlova St., Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197022

Bolshaya Alley, 14, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Moskovskoye Highway, 23, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 196601

nab. Malaya Nevka River, 11, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Embankment of the Malaya Nevka River, 12, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Krestovka River Embankment, 2, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Petrogradskaya Embankment, building 34, lit. B, room 1-N, office 514, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

Embankment of the Malaya Nevka River, 33a, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197376

3V97+R8 Svetogorsk, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Krasnoflotskoye Highway, 16, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198412

Primorskaya St., 8 building 4, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198504

Saint Petersburg Ave., 42, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198510

Akademika Pavlova St, 13, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197022

TD "Burda Moden, Akademika Krylova St., 4, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197183

Lakhtinsky Ave., 115, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197229

Bolshaya Porokhovskaya St., 18, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 195176

Utkin Ave., 2A, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 195027

Irinovsky Ave., 9, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 195279

Sverdlovskaya Embankment, 40, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 195027

Stachek Ave, 206, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198262

526L+RW Redkino, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

97PP+34 Vyritsa, Leningrad Oblast, Russia