The Epidemic and the Tsar’s Flight

The scourge of the ages—cholera, known to humanity since the time of Hippocrates—appeared in Russia in 1829 in the Orenburg and the Astrakhan provinces bordering Persia. Late in the autumn of 1830, it reached Central Russia, then Moscow, and by summer, St. Petersburg.

There is a rapture in battle,

And on the edge of a gloomy abyss,

And in the raging ocean,

Amidst the stormy waves and turbulent darkness,

And in the Arabian hurricane,

And in the breath of the Plague.

These lines were written by Pushkin in Boldino in autumn 1830. By “plague,” the poet meant not only the bubonic “black death” of distant medieval England but also cholera, which that year came to Russia from the far shores of the Ganges. Due to quarantine, Pushkin was stuck for three months at his ancestral estate, gifting Russian literature several poetic and dramatic masterpieces. At the time, cholera was popularly called the “bird of justice,” the “Indian contagion,” “dog’s death,” or also plague—the “contagion” from Latin.

On July 1, 1831, St. Petersburg’s governor-general Peter Essen informed citizens that due to the approaching epidemic, quarantine posts were established at all city entrances. Arrivals to the capital were thoroughly inspected and detained if there was the slightest suspicion of illness.

However, General Essen reported to the Minister of Internal Affairs Zakrevsky: “All measures taken on this matter in this province are very insufficient and unable to prevent the disease from entering its borders and the capital itself.”

In just the first two weeks, more than three thousand people in the capital contracted cholera, of whom one and a half thousand died. Benkendorf recalled those days in Petersburg: “At every step, mourning clothes were seen and sobbing heard. The air was unbearably stifling. The sky was heated as if in the distant south, and not a single cloud obscured its blue. The grass had faded from terrible drought—forests were burning everywhere, and the earth was cracking.”

Civilian and military medical forces were deployed to eradicate the disease, but their strength proved insufficient to overcome it. At that time, doctors did not know the nature of cholera or its transmission routes, so conditions to fight the infection were not established. Emperor Nicholas I, fearing for the lives and health of himself and his family, left Petersburg, moving to his residence in Peterhof. Wealthier city residents followed his example, boarding up their mansions and fleeing to country estates where the disease had not yet reached thanks to the declared quarantine. Alexander Pushkin, living then in Tsarskoye Selo, wrote to his friend Pavel Nashchokin: “Cholera is here, that is, in Petersburg, and Tsarskoye Selo is cordoned off.”

Nicholas I, fearing for the lives and health of himself and his family, left Petersburg. Despite Nicholas’s absence, the capital maintained an appearance of order. The deserted streets, which people ventured onto only out of necessity, were patrolled by mounted police who caught the sick and increasingly abused the people, who could not receive proper medical care. The populace was outraged to learn that Nicholas had left the city while commoners were strictly forbidden to leave Petersburg. Escape was impossible due to the cordon at the city’s border.

Gradually, rumors spread that foreign doctors had brought the disease and were spreading the infection to exterminate the Russian people. It took only a few days for the rumor to sweep the city and sway hundreds. Commoners beat doctors, smashed carriages carrying the sick, and “freed” those being taken to hospitals. They also actively searched for “poisoners,” conducting raids. Those who carried special chlorine lime, recommended by doctors to wipe certain body parts to protect against infection, suffered especially. Frantic people, searching a barely standing man out of fear, would pull a vial from his pocket and beat him nearly to death, suspecting him of poisoning.

Finally, popular outrage and panic, caused by the growing number of sick and the authorities’ blatant inaction, led to an expected outcome. On June 22, riots began in Petersburg: groups roamed the streets attacking “poisoners,” searching cholera carriages, trying to find poison, and fighting police. Suspicious-looking people were seized and searched. One victim of a search recalled:

“Approaching Five Corners, I was suddenly stopped by a petty shopkeeper who shouted that I had thrown poison into his kvass, which stood in a bucket by the door. It was about 8 p.m. Naturally, passersby gathered at the shout, and in less than a minute, I found myself surrounded by a crowd growing every moment. Everyone shouted; I vainly assured them I had no poison and threw none: the crowd demanded to search me. I took off my frock coat with heraldic buttons to show I had nothing; my soul was uneasy lest the crowd see foreign magazines, especially Polish ones, among them. The crowd was not satisfied with the coat; I had to remove my vest, undershirt, boots, even underwear, and was left in just a shirt. When those surrounding me, flooding the street so much that traffic stopped, saw I had nothing suspicious, someone in the crowd shouted I was a ‘werewolf’ and that he saw me swallow a vial of poison. The most annoying was some gentleman with a woman named Anna on his arm—he shouted the loudest and harassed me the most...”

In the city, a cholera hospital was urgently organized at Sennaya Square, at 4 Tairov Lane, where police and soldiers forcibly took the sick. On July 4, this sparked an outbreak of discontent; the gathered crowd shouted that their relatives were being taken to the hospital to be killed. The hospital was destroyed, and all medical staff working there were torn apart and thrown out of windows. General Ivan von Hoven, who left memoirs about the cholera riot days, wrote: “The hospital was smashed, the sick were carried out on beds to the square, doctors, paramedics, and the pharmacist were killed, and the staff dispersed.” One of the killed was Lenin’s great-uncle Dmitry Blank, who worked at the Central Cholera Hospital.

Lenin’s future grandfather, Dmitry’s brother Alexander, was so shocked by his brother’s death that he could not work for a year afterward.

There is a Petersburg legend that Emperor Nicholas I was able, without violence, to pacify the rioting people, who were struck by their tsar’s eloquence and fell prostrate as soon as the autocrat began reproaching them with the words, “Shame on the Russian people, forgetting the faith of their fathers, imitating the frenzy of the French and Poles.”

However, history tells us that bloodshed and military intervention were unavoidable. When officials remaining in the city faced the popular riot, whose instigators smashed hospitals and killed doctors, city leaders gathered for a meeting at Count Peter Essen’s residence—a brilliant military man, infantry general, appointed Petersburg governor-general in early 1830. During the meeting, they decided to call in military force: Guards regiments, reinforced with artillery, surrounded the square, and infantry, as well as the Sapper and Izmailovsky battalions, struck the crowd with a massive blow.

An eyewitness who witnessed the events at Sennaya Square described his impressions: “Suddenly, two Cossacks appeared from Nevsky, or one Cossack and one gendarme—I don’t remember well. They boldly rode into the crowd and began dispersing people with whips... Within a minute, one of them, the Cossack, disappeared from this sea of heads; where he went, I don’t know; probably pulled off his horse. The other, I think the gendarme, seeing things were going badly, wisely decided to retreat and quietly rode back toward Nevsky... Within five or ten minutes, a carriage drawn by four horses appeared from Nevsky, with a footman. Two military men sat inside—in greatcoats; one was a gray-haired old man, Governor-General Essen, the other young, his adjutant.” A large group of rioters ran into the carriage carrying General Essen. They nearly killed him, but arriving troops saved the governor-general.

When the troops finally restored relative order, Nicholas entered the capital, choosing the lesser of two evils: ignoring his fear of cholera, wisely deciding that the raging mob was far more terrifying.

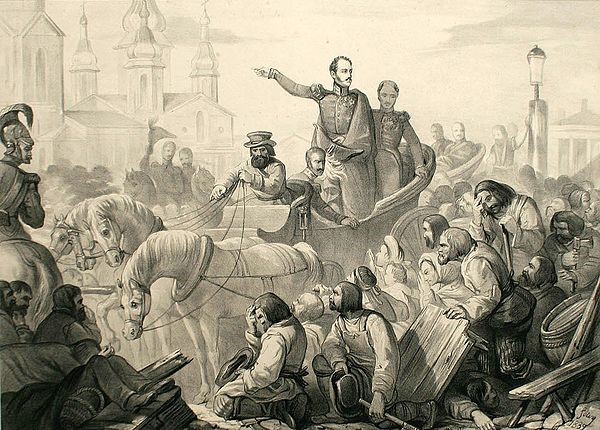

Many eyewitnesses of that time left memories: Count Benkendorf, Baroness Frideriks, court physician Arendt, St. Petersburg’s civil governor Khrapovitsky, writer Panayeva, and Emperor Nicholas I himself. The scene of quelling the cholera riot is also depicted on one of the bas-reliefs decorating the pedestal of Nicholas I’s equestrian statue on St. Isaac’s Square in St. Petersburg.

According to Benkendorf’s official notes, “The sovereign stopped his carriage in the middle of the crowd, stood up in it, looked around at those pressing near him, and thundered: ‘On your knees!’”

The entire many-thousand-strong crowd, removing their hats, immediately bowed to the ground. Then, turning to the Church of the Savior, he said: “I have come to ask God’s mercy for your sins; pray to Him for forgiveness; you have grievously offended Him. Are you Russians? You imitate the French and Poles; you have forgotten your duty of obedience to me; I will be able to bring you to order and punish the guilty. For your behavior, you are answerable before God—I am. Open the church: pray there for the repose of the souls of those innocently killed by you”… The crowd reverently bowed to their tsar and hastened to obey his will.”

Bas-relief “Cholera Riot of 1831” Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

One of the bas-reliefs on the monument to the emperor is dedicated to this event.

Of course, Nicholas reproached his subjects and, as townsfolk whispered, even kissed someone in the crowd, which brought tears and cries of “We will die for our father the tsar” from the most sensitive. It was also said that the tsar was unusually convincing in his appeal, but history remains firm: the raging crowd was subdued by troops, not by the emperor’s eloquence.

However, this fact did not tarnish the tsar’s reputation; it was as if forgotten, accepted as truth what was not true. Otherwise, how to explain that on one of the bas-reliefs decorating Nicholas’s monument on St. Isaac’s Square, there is a scene depicting the calming of the people by the tsar?

The cholera epidemic ended in Petersburg in autumn 1831, claiming seven thousand lives. The last outbreak in the city occurred in 1918, when cold raged, devastation prevailed, and medical forces were fully committed to the fields of the Civil War.

Sources:

https://dzen.ru/a/aGefTfpxNXDz4MI9

https://ru.ruwiki.ru/wiki/%D0%A5%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B5_%D0%B1%D1%83%D0%BD%D1%82%D1%8B

https://proza.ru/2024/10/20/635#:~:text=%D0%A0%D1%8F%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BC%20%D1%81%20%D0%A1%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B9,https%3A//ihospital.ru/

https://spb.aif.ru/society/people/holernyy_bunt_v_peterburge_kak_narod_vosstal_protiv_epidemii

https://www.perm.kp.ru/daily/27688/5078497/