Millionnaya St., 7, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

The origin of Catherine I is unclear. Her relatives are named Skovorotsky in some documents, Skovorodsky, Skovoronsky, and even Ikavronsky in others. According to Relbig's testimony, the surname "Skavronsky" was adopted at the suggestion of Count Peter Sapieha.

The widely accepted official version is that the founders of the Russian noble family were her biological brothers. However, due to the scarcity and obscurity of data, and the possible deliberate destruction of documents during Peter's reign, other versions of Catherine's origin were later proposed, according to which she was a cousin, not a biological sister of the Skavronskys, or another relative. It is noted that Peter I himself called Catherine not Skavronskaya, but Veselevskaya or Vasilevskaya, and in 1710, after the capture of Riga, in a letter to Repnin, he named completely different names as "relatives of my Catherine" — "Yagan-Ionus Vasilevski, Anna-Dorothea, also their children."

It is known that in 1714, the Russian general-commissioner at the Courland court, Peter Bestuzhev, received through Matvey Alsufyev a decree from St. Petersburg "to search in Kryshborh for the surnames Veselevsky and Duklyas." On June 25, 1715, Bestuzhev presented a note with the data he had obtained, in which he reported that Katerina-Liza Han was twice married — to Veselevsky and Duklyas, and her sister Dorota "was married to Skovorodsky, had two sons and four daughters, was Lutheran by law; one (son) Karl, the other Fritz in Polish Livonia, one daughter Anna, another Dorothea, both married in Polish Livonia." He reports that Dorota's third daughter "Katerina lived in Kreisburg with her aunt Maria-Anna Veselevskaya, whom at the age of 12 was taken to Livonia by a Swedish Marienburg pastor." Bestuzhev's information is considered controversial and contradictory, particularly regarding the ages of the mentioned persons, which suggests that Katerina was not Dorota's daughter but the daughter of her sister, possibly Elizabeth Moritz. It is unclear why many years later Catherine ordered to search among all the persons mentioned only the Skavronskys, neglecting their other blood relatives.

Another surname associated with Catherine I is Rabe. According to some data, this was the surname of her first husband, a dragoon; according to others, it was her maiden name, and a certain Johann Rabe was her father. The question of her belonging to various Baltic ethnic groups, and even baptized Jews, is discussed. For example, although her tutor, Pastor Gluck, during the described events was close to the court and lived for many years in Moscow, where he headed the first Moscow gymnasium, his testimonies and information about Catherine's origin have not been found anywhere or, quite possibly, were destroyed.

After ascending the throne, Catherine granted the Skavronskys the title of count, without calling them her brothers, and in her will, the Skavronskys are vaguely referred to as "close relatives of her own surname." Catherine nowhere in her decrees and orders mentioned kinship with the Skavronskys, whom she showered with gifts and honors. In correspondence between Prince Repnin and cabinet secretary Makarov, there is also no hint of their kinship with the Empress; they are named by their first and last names, or expressions such as "these people, the husband of this woman, that woman," are used. Elizabeth Petrovna calls the Yefimovskys, Skavronskys, and Hendrikovs "related families of her beloved mother."

It is reported that in 1721, when Peter I and Catherine were in Riga, a serf peasant woman named Christina Skovoroshchanka suddenly appeared at the court, who "claimed" to be Her Majesty's sister and requested an audience. From the letters of the Riga governor-general Prince Repnin, it is known that "that woman was with Her Majesty and then sent back to her home" with a grant of 20 chervonets.

The first of Catherine I's "brothers," Karl Samuilovich Skavronsky, allegedly arrived in St. Petersburg during Peter I's lifetime.

At the same time, there was a joke circulating in St. Petersburg about how the sovereign first saw Karl Samuilovich while her late husband was still alive. He was brought to the capital. At Shepelev's house, the Empress was introduced to her brother. Catherine Alekseevna fainted from shame. "No need to blush," said the Emperor, "I recognize him as my brother-in-law, and if there is any fault in him, I will make a man out of him." The story about the fainting is retold by Voltaire in "Histoire de l’empire de Russie sous Pierre le Grand." Vilboa and Voltaire report that Karl was found in a tavern, as a servant, declared himself the brother of a high-ranking lady, etc.

However, the pre-revolutionary Russian Biographical Dictionary by Polovtsov reports that he arrived in St. Petersburg with his family at the end of 1726 (Peter I died on February 8, 1725). Polovtsov writes about Karl: "His past is certainly shrouded in complete darkness, and it remains unknown under what exact circumstances Karl Samuilovich was found. In a letter from Prince Repnin dated December 15, 1722, it is indicated that a certain peasant was found, taken under strict guard, and sent to Moscow to cabinet secretary Makarov. According to K. I. Arseniev's assumption, this certain peasant is Karl Samuilovich. In a letter from Prince Repnin dated April 7 of the following year, it is reported that Karl's wife was found in the village of Dogaben; she was persuaded to go to her husband but refused, despite assurances that her husband 'is kept in every comfort.' It is difficult to say in what conditions Karl Samuilovich lived from 1723 to the end of 1726 and from where he came to St. Petersburg." Initially, he was called Ikavoronsky, a name probably a distortion of Skavronsky, which was actually given to him and stuck. It is unknown who first came up with this Polish name, but it is believed that Count Sapieha suggested it.

Count Karl Skavronsky received a splendid house in St. Petersburg. His maintenance was magnificent, befitting the lifestyle of the most noble private individuals. To be able to cover the expenses associated with such a status, Count Skavronsky was not only given cash but also granted such noble estates in Russia that to this day the wealth of the Skavronsky family is considered among the most significant in the Russian Empire; and this means a lot, because in Europe there are few countries where the highest nobility was as wealthy as in Russia. To this should be added precious stones and expensive clothes. Such enormously lavish gifts as those received by Skavronsky, his sisters, and their entire family aroused envy... However, the dissatisfaction of the courtiers was gradually subdued because they saw that these upstarts did not receive any of the most noble positions in the state, which, however, they would not have been able to occupy due to their extreme ignorance. For example, Karl Skavronsky, although he was the sovereign's brother, became only, as far as we know, a chamberlain, but did not receive any court position or a single order.

We cannot determine the time of his death precisely; but it seems that he died already during the reign of Peter II, professing the Catholic faith. He brought with him to Russia three sons and two daughters. Another daughter was born here. These children were mostly raised in the Greek faith. The sons were named Ivan, Martin, and Anton. Only one of them, Martin, left offspring. Martin Skavronsky was already 14 years old when his father became a nobleman. His upbringing was entrusted to Academician Bayer, who was to ensure his pupil's "good behavior and knowledge in sciences"; he also studied foreign languages. With the establishment in 1731 in St. Petersburg of the Landed Noble Cadet Corps, he was enrolled among its wards.

In 1735, following a denunciation by his servant that Skavronsky spoke indecent words about Empress Anna Ivanovna, he was interrogated by the Secret Chancellery. The Empress deigned to decree: "To the said Count Martin Skavronsky, for the serious insolence in words committed by him, to administer punishment, to be whipped mercilessly, and after the execution of that punishment, to release the said Skavronsky and his people from the Secret Chancellery."

The accession of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna sharply changed the position of Count Martin, her cousin. In 1742, he remained the only male representative of the family. Perhaps this largely explains the abundant distinctions and awards that befell Skavronsky during the entire reign of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. Ranks of chamberlain (1742), chamberlain (July 1744), Ober-Hofmeister, General-Anshaf, the rank of General-Adjutant, the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, the richest estates (for example, the village of Kimry, confiscated from Countess E. I. Golovkina), and thousands of serfs — all these grants from Empress Elizabeth Petrovna significantly elevated Skavronsky among the wealthy and noble Russian aristocracy. At that time, his carriage was famous in St. Petersburg: entirely decorated outside with rhinestones, it cost 10,000 rubles. In his last years, in 1748, he was chamberlain and a knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, which he received from Empress Elizabeth in 1744. In 1764, he signed the death sentence of the unfortunate Mirovich. His wife was a lady-in-waiting to Empresses Elizabeth and Catherine II and was still alive in 1799.

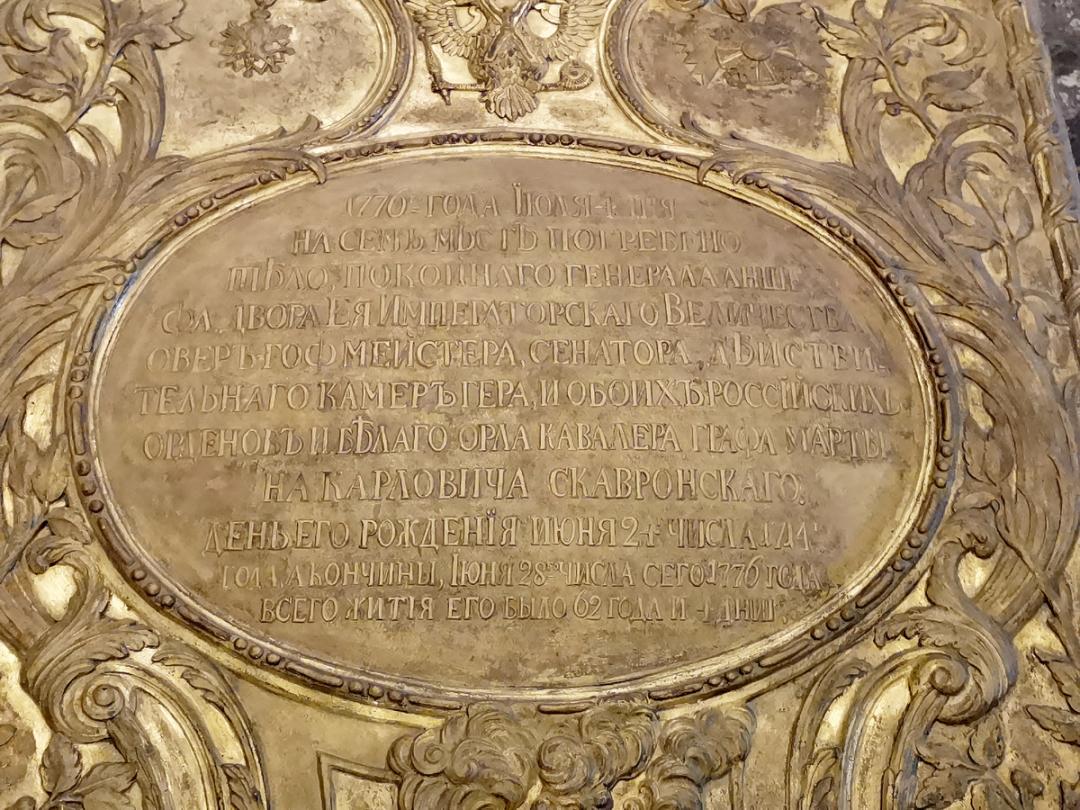

Annunciation Burial Vault of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. Tombstone of Count Martin Karlovich Skavronsky (1714-1776) — nephew of Catherine I, General-Anshaf, Ober-Hofmeister.

Annunciation Burial Vault of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. Tombstone of Count Martin Karlovich Skavronsky (1714-1776) — nephew of Catherine I, General-Anshaf, Ober-Hofmeister.

The daughters of Count Karl Skavronsky were named: Sophia, Anna, and Catherine.

Tombstones from the gravestone of the cousin of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, Countess Anna Karlovna Vorontsova (1722-1775), née Countess Skavronskaya, and Count Martin Karlovich Skavronsky (1714-1776) — nephew of Catherine I, General-Anshaf, Ober-Hofmeister.

Tombstones from the gravestone of the cousin of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, Countess Anna Karlovna Vorontsova (1722-1775), née Countess Skavronskaya, and Count Martin Karlovich Skavronsky (1714-1776) — nephew of Catherine I, General-Anshaf, Ober-Hofmeister.

Sophia Karlovna was granted, having just arrived in St. Petersburg, the position of lady-in-waiting to her aunt, Empress Catherine I. But very soon she married Count Peter Sapieha, whom we have already mentioned. The Empress, who owed him some gratitude for finding her relatives, awarded him the Alexander Order in 1726. Sapieha, one of the first magnates in Poland, considered it an honor to marry a peasant woman who was the niece of the Russian Empress. Sophia had several children and died a Catholic.

Sources:

Georg von Helbig: Random People in Russia

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skavronsky,_Martyn_Karlovich

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skavronskys

https://azbyka.ru/otechnik/Spravochniki/russkij-biograficheskij-slovar-tom-18/548

Unnamed Road, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199178

Rubinstein St., 7, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191025

Griboedov Canal Embankment, 2B, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Sadovaya St., 2, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

Malaya Morskaya St., 10-4, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Malaya Sadovaya St., 8, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

Fontanka River Embankment, 2, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191187

Nevsky Ave., 28, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Kazan Square, 2, Saint Petersburg, 191186

Admiralteysky Ave, 12, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

Palace Square, 6, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Nevsky Ave., 16, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Nevsky Ave., 39A, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

Nevsky Ave., 39, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

Nevsky Ave., 15, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Dvortsovaya Square, 2, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

Bolshaya Morskaya St., 20, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Dvortsovaya Embankment, 2E, Saint Petersburg, Leningrad Region, Russia, 191186

Petrovskaya Embankment, 6, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197046

Kronverksky Ave, 7, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197046

Barmaleeva St., 5, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197136

Admiralteysky Canal Embankment, 2t, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190121

7th Line V.O., 16-18, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

Nevsky Ave., 72, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191025

Malaya Morskaya St., 24, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

2 Zodchego Rossi Street, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

X83G+65 Petrogradsky District, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Universitetskaya Embankment, 17, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

WCV4+84 Krasnogvardeysky District, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Universitetskaya Embankment, 3, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

Angliyskaya Embankment, 76, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

Arsenalnaya Embankment, 7, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 195009

1st Elagin Bridge, 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197183

Nevsky Ave., 18, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Golitsynskaya St., 1x, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 194362

1 Summer Garden St., Saint Petersburg, Leningrad Region, Russia, 191186

108 Lenin Ave, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198320

4th Line V.O., 5, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034

Kamennoostrovsky Ave., 44B, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197101

Malaya Morskaya St., 24, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

Odessa St., 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191124

Fermskoye Highway, Building 41, Block 8, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197341

Fontanka River Embankment, 166, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190020

Krasnogradsky Lane, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190068

San-Galli Garden, Ligovsky Ave., 64, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191040

Ligovsky Ave., 10, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191036

Ligovsky Ave., 10/118, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191036

Gorkovskaya, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197101

4 Kvarengi Lane, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191060

Spasskaya, Saint Petersburg, Russia

W8F9+X7 Admiralteysky District, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Sennaya Square, 5, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190031

Brinko Lane, 4, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190068

Ligovsky Ave., 50, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191036

pr. Stachek, 108A, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198207

Nevsky Ave., 35, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191023

12 Millionnaya St., Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Galernaya St., 60, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000