In 1904, plots 1/2 and 3 on Kronverksky Prospekt were acquired by Matilda Kshesinskaya. The purchase (for 88 thousand rubles) was made by the nobleman Kollin in his own name, as a trustee. However, the sales record stated that the place was bought with Kshesinskaya’s money. Official documents in her name were issued on September 10, 1905 (old style). Before that, the ballerina lived on English Avenue.

Kshesinskaya commissioned the project and construction of the mansion to the academician of architecture von Hogen. The interiors were created with the participation of the young architect Alexander Dmitriev. The realized project is the result of close collaboration between the architect and the client. Von Hogen developed the mansion project in 1904. The drawings he submitted to the City Administration are dated July 26. The project differs little from the constructed building. The final project was published in the journal "Zodchiy" in 1905.

By autumn 1905, the building was constructed in rough form. In the ballerina’s memoirs, it is said that she moved into the new house around Christmas 1907. Kshesinskaya was involved in the details of the interior arrangement and decoration, deciding on the design of some rooms. According to von Hogen, the interior decoration was conceived without excessive luxury. More than 70 interior drawings were made by von Hogen and his student Dmitriev. Architect Dubinsky also worked on the mansion’s interiors, but it is unknown whether his proposals were implemented. Von Hogen’s assistant during the mansion’s construction was Samoylov, a student of the Institute of Civil Engineers.

What Kshesinskaya wrote about this in her memoirs: "I commissioned the plan from the very famous architect Alexander Ivanovich von Hogen in Petersburg and entrusted him with the construction as well. Before drawing up the plan, we discussed together the arrangement of rooms according to my wishes and the conditions of my life. I outlined the interior decoration of the rooms myself. The hall was to be done in the style of Russian Empire, the small corner salon in the style of Louis XVI, and I left the rest of the rooms to the architect’s taste, choosing what I liked best. I ordered the bedroom and the toilet in the English style, with white furniture and cretonne on the walls. Some rooms, like the dining room and the adjacent salon, were in Art Nouveau style. All the stylish furniture and that intended for my personal rooms and my son’s rooms I ordered from Meltzer" -

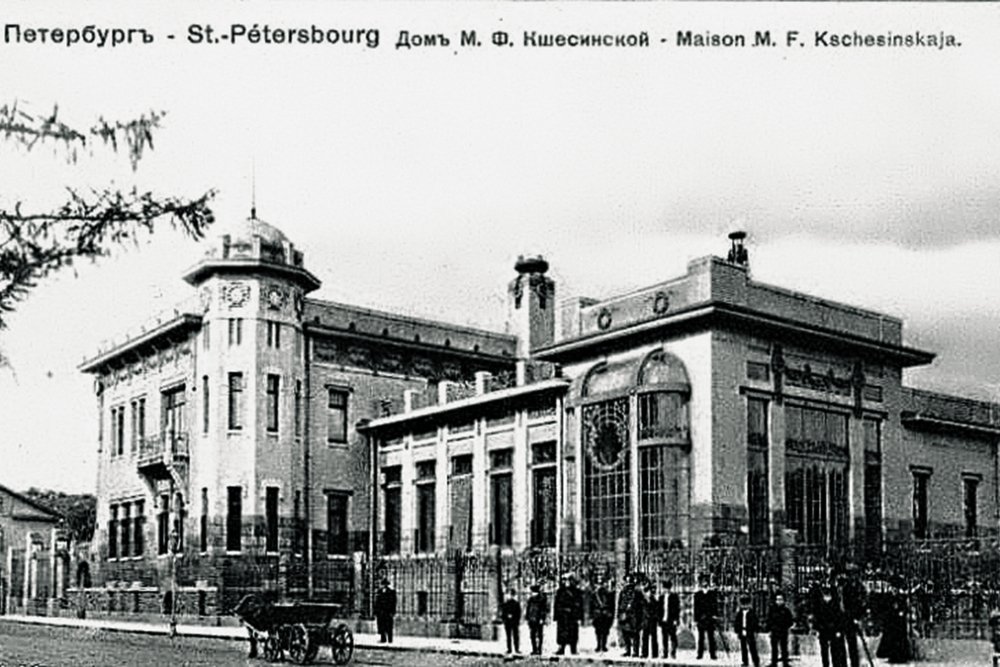

Kshesinskaya’s mansion became a classic example of Petersburg Art Nouveau. In 1907, at the competition for the best facades of new buildings, the City Administration awarded it a silver medal.

Except for a small facade part on Kronverksky Prospekt, the entire building is located in a garden. The living quarters face the sunny side. Only the staircase, vestibule, and toilet face north. The front garden, a delicate fence on the south side, and a gazebo-pergola on the corner decorate the building.

The building’s architecture in Art Nouveau style attracts attention with its free asymmetrical composition, elegance, and variety of forms. The different heights of its parts and window sizes reflect the features of the interior layout. The front garden, fence, and gazebo complete the building’s appearance. The exterior has survived almost unchanged. Since the revolutionary events, the original interiors and furniture of the mansion have almost completely disappeared. Only the vestibule, antechamber, and staircase (with losses) remain from the interior decoration. The interior layout combines free volumes with ceremonial enfilades. The one-story wing contains two parallel enfilades. The internal organization of rooms is visible behind the external volumes of the building.

The building’s plinth is laid with Valaam red granite of rocky texture. Above it runs a belt of gray Serdobol granite. The walls are faced with light Zigersdorf brick. Against their background stand out dark blue ceramic friezes, metal structures, and wrought elements. The courtyard facades are simply decorated.

On the northern side of the plot, a small wing with living quarters and a common dining room was allocated for the servants. In the backyard were a laundry, cowshed, carriage and automobile shed. The owner’s pride were the dressing rooms (upstairs and downstairs), kitchen, and wine cellar with a buffet, where dinners were often held. Also in the semi-basement were a pantry, icehouse, and boiler room. The furnishing of the utility part and servants’ rooms was done by the furniture firm Platonov.

The main entrance to the building was located from the small northern courtyard. From the vestibule opened the main enfilade. The enfilade includes the vestibule, antechamber, large hall, and winter garden.

Matilda Felixovna Kshesinskaya was born into a Polish aristocratic family on August 19, 1872, in Ligovo near Petersburg. Her father, Felix Ivanovich, graduated from the Warsaw Ballet School and danced at the Warsaw Grand Theatre. In 1853, he moved to Petersburg, joined the Mariinsky Theatre troupe, and was considered the first "mazurka dancer" in Russia. Her mother, Yulia Kshesinskaya, was a ballet artist of the Mariinsky Theatre who left the stage for the family. In 1890, Matilda graduated with honors from the theatrical school. At the graduation evening, she met the Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich. Soon she became the first Russian prima ballerina on the Mariinsky Theatre stage, displacing Italian ballerinas. In February 1900, the ballerina met Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich. In 1902, they had a son, Volodya.

In her mansion, Kshesinskaya held receptions. Frequent guests were actors from the Alexandrinsky Theatre. Italian singer Lina Cavalieri, Sobinov, and Shalyapin sang here. Jeweler Karl Fabergé and dancer Isadora Duncan visited. The ballerina received her colleagues Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Sergei Diaghilev here. The receptions were attended by Grand Dukes Andrei Vladimirovich (the ballerina’s future husband), Boris Vladimirovich, and Kirill Vladimirovich. The emperor’s cousin, Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich, managed the ballerina’s affairs and bought her a dacha in Strelna. At the mansion and dacha, home performances, improvised concerts, and "kapustniks" were held. In the 1900s, Kshesinskaya brilliantly performed both in Marius Petipa’s classical ballets and in new ballets by Fokine, successfully touring Europe and Russia. The mansion’s owner was a loving, caring mother and exemplary hostess. The ballerina’s French chef Denis, who accompanied her on all trips, was famous throughout Petersburg.

On February 22, 1917, Kshesinskaya gave her last dinner in the mansion. On February 27, the ballerina, her son, and tutor left the mansion after receiving threats. The empty building was soon looted by a large crowd of marauders, and a few days later was occupied by soldiers of the workshops of the reserve armored division, who were mainly housed on the lower floor. One of the agitators reported this to the Petersburg Bolshevik Committee, which, after the party came out of hiding, was cramped in two small rooms in the attic of the Petrograd Labor Exchange (Kronverksky Prospekt, 49) and desperately needed premises for work. Member of the PC Petr Dashkevich was sent to negotiate with the "armored men" (as the soldiers of the armored division were called). He quickly found common ground with them, and on March 11, the PC RSDLP (b), its Military Organization, and then the Central Committee of the Bolshevik party moved into Kshesinskaya’s mansion, which, as the Petrograd newspapers wrote, became the "main headquarters of the Leninists."

Now fierce meeting passions constantly boiled around the mansion. The wife of the famous historian academician S. F. Platonov, living with her family on Kamennoostrovsky Prospekt, wrote in her diary: "There is always a crowd around it and someone is speaking — it is no longer Lenin himself who speaks the most..., but someone from the 'Leninists,' fierce disputes occur between the 'Leninists' and their opponents, and those who disagree with Lenin are sometimes arrested, and sometimes, they say, the Leninist speaker has to hastily escape into the yard or house to avoid being beaten." Meanwhile, its true owner, having somewhat recovered from the experienced turmoil, decided to try to return home. But it turned out that the uninvited guests had no intention of leaving the cozy mansion, which also had a very advantageous strategic location: nearby was the Peter and Paul Fortress, not far in the People’s House after the February Revolution soldiers of the 1st Machine Gun Regiment — one of the most revolutionary units of the garrison — were stationed, and the working outskirts of the Vyborg side were within arm’s reach. On the other hand, the city center — Nevsky, or as it was called in ’17, the "Milyukov" Prospekt — could be reached in fifteen minutes.

The ballerina quickly grew bold and decided to reclaim her house. She tried to talk with the Bolsheviks. They spoke politely but refused to vacate the premises and openly mocked the "poor" ballerina. Kshesinskaya went to various authorities. The only help from the "revolutionary democracy" was a resolution from the executive committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. The document stated that the seizure of private property was unacceptable. The Petrograd Soviet called on the "armored men" to vacate the building. However, the resolution did not help, nor did the prosecutor’s demand to return the building to the owner. In revolutionary Petrograd, only decisions backed by concrete military and political power had force. Minister of Justice Alexander Kerensky told the ballerina that the house could not be taken back by force, as it would end in bloodshed and further complicate matters.

Moreover, public opinion was clearly not on Kshesinskaya’s side. She was the object of rumors and ridicule.

In the drawing titled "Victim of the New Order," a ballerina lies on a bed. The caption reads: "Matilda Kshesinskaya: 'My close ties to the old government were easy for me: it consisted of only one person. But what will I do now, when the new government — the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies — consists of 2,000 people?!'"

Even among the liberal intelligentsia, the opinion was popular that the ballerina’s house should become public property. However, a couple of months later, "terrible Lenin and the Leninists" appeared to the public as much more dangerous than the "tsar’s favorite," historians write.

Having exhausted almost all possibilities, Kshesinskaya sued the Bolsheviks and their leader Lenin. On the morning of May 5, 1917, at house No. 9 on Bolshaya Zelenina Street, where the magistrate’s chamber of the 58th district was located, there was unusual excitement. The courtroom was packed to capacity. Some of the curious asked, "Are they really trying the Leninists here?" To avoid possible incidents, heightened security measures were taken. An enhanced detachment of rifle-armed militiamen guarded the entrance. Everyone wishing to attend the session was asked about the purpose of their visit, and numerous representatives of the Petrograd press were required to show editorial credentials. Everyone eagerly awaited noon, when the trial was to begin. But to better understand the sensational trial’s background, one should go back a little over two months...

The party in this trial was defended by Lithuanian revolutionary and lawyer Mechislav Kozlovsky. At the May 5 trial, he stated that the Bolsheviks almost saved the building from destruction.

"[Revolutionary organizations] occupied it when it was empty, when the raging masses were destroying Kshesinskaya’s palace, considering it a nest of counterrevolution, where all the threads connecting Kshesinskaya to the tsar’s family converged, who, according to the masses’ understanding, was if not a member of the tsar’s family, then at least the favorite of the overthrown tsar," Kozlovsky reasoned at the trial.

The defendants listed at the trial by the plaintiff were: "1. Petrograd Committee of the Social-Democratic Workers’ Party; 2. Central Committee of the same party; 3. Central Bureau of Trade Unions; 4. Petrograd District Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party; 5. Club of Military Organizations; 6. Candidate of Law V. I. Ulyanov (pseudonym — Lenin); 7. Assistant Attorney S. Ya. Bagdatyev; 8. Student G. O. Agababov." The plaintiff’s lawyer Vladimir Khesin insisted that even during the revolution there is law. In response to Kozlovsky’s words about the angry crowd and the tsar’s favorite, the lawyer said the court is no place for "rumors and street talk."

"Does the crowd say anything? — he said. — The crowd talks about traveling in a sealed train through Germany and about German gold brought to my client’s house. But I did not repeat any of this in court."

The court ultimately ruled in favor of Kshesinskaya. The Bolsheviks had a month to vacate the premises. As expected, the enforcement of the court decision was delayed. The Bolsheviks and their supporters actively resisted eviction, threatening to use weapons. They simply had nowhere to go, and the headquarters in the city center was very convenient. The issue of the mansion had to be resolved in the context of the general political situation, which was increasingly approaching civil war.

By early July, the confrontation between left-wing radicals and other revolutionaries and the Provisional Government almost escalated into open armed conflict. Armed demonstrators with Bolshevik slogans roamed Petrograd, demanding the transfer of power to the Soviets. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks considered these demonstrations counterrevolutionary.

On the evening of July 5, reliable units summoned from the front, supporting the official authorities, arrived in Petrograd. Reports about Lenin’s connections with Germany, which influenced public opinion and the mood of most military units, were also published. The situation shifted in favor of the Provisional Government.

Significant military forces were allocated to evict the Bolsheviks from Kshesinskaya’s mansion: eight armored cars, soldiers, a machine gun team, and two artillery pieces. On the morning of July 6, RSDLP(b) party members hurriedly left the building, which was immediately occupied by a combined detachment of Provisional Government troops.

"The soldiers who stormed the building wreaked complete havoc in the premises of the Bolshevik organizations," write the authors of the book "Around the Winter Palace." The looters had not only ideological motives — many soldiers believed rumors that Germany generously financed the Bolsheviks and hoped to find "German millions" in the mansion.

Destruction of Kshesinskaya’s mansion by Provisional Government troops. July 6, 1917

The book "Around the Winter Palace" contains the memoirs of Staff Captain Ivan Mishchenko — head of the machine gun team of the 1st Motorcycle Battalion of the 1st Cavalry Corps of the Northern Front. The manuscript of his memoirs was found in the State Archive. Mishchenko participated in the building’s occupation and was its commandant for some time afterward. Apparently, the house was already abandoned by the Bolsheviks when the staff captain and soldiers entered.

"There was complete chaos in the house," he wrote. Cigarette butts, food remains, empty cognac bottles were scattered everywhere; furniture upholstery and curtains were torn; armchairs and sofas were broken. On the lower floor, beds, mattresses, books, tables, broken figurines, and clothes were piled up in heaps.

"In the winter garden, apparently, someone practiced saber cuts, so only the stems remained of the expensive tropical plants. Madame Kshesinskaya’s wonderful bathroom was turned into a cesspool; various items, from cigarette butts to human excrement, lay at the bottom of the pool," Mishchenko wrote in his memoirs.

The next day, in the presence of a commission from the Provisional Government, two rooms were broken into in the mansion, the keys to which the Bolsheviks had taken with them. Correspondence of the RSDLP(b) was found there.

"When the commission interrogated the janitor... he, giving testimony and seeing a hat, said it was Comrade Lenin’s hat. The commission sat for several days," recalled the staff captain. "Once, one volunteer member of the commission said to me: 'Yes, it’s a pity we took so long to deal with the Bolsheviks. Look. They have already taken all of Russia into their hands; from Lenin’s correspondence, it is clear that everything is already done in this direction.'"

After the Bolsheviks’ eviction, Matilda Kshesinskaya could not return to her home because this time it was occupied by soldiers of the 1st Motorcycle Battalion, who had liberated the building. No one was in a hurry to evict them.

Lawyer Khesin continued to file lawsuits, but the ballerina realized waiting was pointless. On July 13, 1917, she left Petrograd and went to Kislovodsk, where Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich awaited her. In February 1920, she left Russia forever.

Kshesinskaya died in 1971 in Paris, just a few months short of her 100th birthday.

After the October events of 1917, the ballerina’s mansion came under the control of the Petrograd Soviet. Later, it housed the "Ilyich Corner," the Society of Old Bolsheviks, and the Museum of the Great October Socialist Revolution. After the USSR’s collapse, the State Museum of Political History of Russia was opened in the house. Everyone knows there is a museum on Gorkovskaya, but few remember that such a vivid and real history is connected with this beautiful house. The story of one of the most beautiful women of the time of the Russian Empire’s demise.

Filming of the movie "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson" took place in and around this mansion in the episode "Deadly Fight," where the "Bagatelle" club was located. Lenin and his comrades once used this club’s entrance.

Through this archway passed the carriage carrying Holmes to his meeting with Moriarty, and in the next episode, Watson, disguised as a priest, will pass here in a cab drawn by old lady Meadows.

Sources:

https://kudago.com/spb/place/osobnyak-kshesinskoj/

https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-40417656

https://family-history.ru/material/history/place/place_4.html

Yulia Demidenko, Vladlen Izmozik, Yulia Kantor et al.: 1917. Around the Winter Palace

https://www.citywalls.ru/house3962.html

Bobrov V.D., Kirikov B.M.: Kshesinskaya Mansion