Bolshaya Morskaya St., 43, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

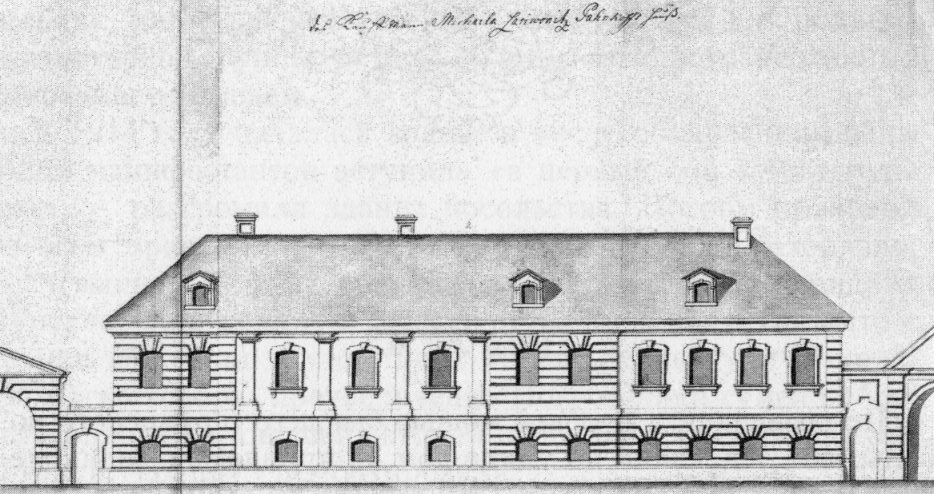

The first stone house on the plot was built in the early 1740s for the merchant Mikhail Panov (possibly Pankov). Originally, the house was one-story (on high cellars), with 11 windows on the facade; the third floor was added in the second half of the 18th century.

Panov sold the house to Matrona, the widow of State Councilor Petrishchev. From 1781, the house was rented to tailor Johann Sievers, and in 1785 it was sold to jeweler Krestyan Ivanovich Hebelt (who also owned house No. 41). At the beginning of the 19th century, the house was owned by Baroness Sofia Ivanovna Velio (Fellio), and in the 1820s by Anna Wilhelmina, wife of Peter Severin, a court banker and merchant. In 1824, Baron Ludwig Wilhelm Tepper de Ferguson lived in the building; in 1827, the Senate prosecutor and later senator Pyotr Sergeyevich Kaisarov resided there. In 1829, the house was acquired by Sofia Alexandrovna, wife of General Pyotr Kirillovich Essen. The Essen family sold the building and plot to Pavel Nikolaevich Demidov for 240,000 rubles on February 14, 1836; on February 25, Demidov bought the neighboring house No. 45 from Auguste Montferrand. That same year, Montferrand developed a reconstruction project for the buildings for the new owner. "This construction is to be completed this summer and will serve as a new decoration of the city." The architect was very busy at the time with the construction of St. Isaac's Cathedral and took on the Demidov project only as a favor. The mansion was to be solid, sturdy, and elegant, to clearly show how wealthy its owner was.

The building has a small light courtyard, and the service wing’s windows face a second small courtyard. The facade of the three-story building features many details. The first floor is decorated with rustication made of white Italian marble; in the middle of the building, white marble atlantes and caryatids hold the balcony of the second floor. The plinth is clad with gray polished Serdobol granite. The second floor is adorned with pilasters. Above the balcony is a marble sculpture "Glory" by T. Jacques, with winged figures holding the coat of arms. On either side of the gates are niches for fountains, lined with white polished marble; they are now empty, but previously contained columns decorated with cupids.

The decoration of the main rooms of the house used gilded bronze, malachite (columns and fireplace in the main hall), various types of marble, and carving. The interiors were created by Bosse and Viggi. Before malachite was used to decorate the mansion, it was considered unsuitable for interior cladding; Demidov’s hall became a model for the decoration of the Winter Palace and the iconostasis of St. Isaac's Cathedral.

In the vestibule and on the main staircase, there are several windows with etched glass, some originals (presumably early 20th century), others reconstructions from the 1990s. Four double-leaf windows in the vestibule on the first floor have semicircular blind transoms; the glass is solid matte, with a frame of repeating cross-flowers in a circle with two buds on the sides, and four-petaled rosettes in the corners. On the staircase between the first and second floors, there are three single-leaf windows, also with matte glass: two windows face the courtyard and one faces a side room; the perimeter band on the first floor features images. In the semicircular part, a large two-handled vase is painted, with two burning torches in the center connected by a garland of laurel leaves; between the flames is a rosette, a large flower in a circle.

At the center of the main facade were built gates, niches with fountains, and a balcony, around which stood atlantes and caryatids. Above them were figures with the Demidov coat of arms, created by Théodore-Joseph-Napoléon Jacques. But perhaps the most famous interior solution was the Malachite Hall. This was the first time malachite was used for interior cladding.

The magazine "Capital and Estate" in 1914 wrote: "This hall is a model of taste and luxury in the purest Louis XV style. The columns supporting the ceiling and those along the walls are made from whole pieces of malachite and represent a very great value. The fireplace is also malachite. In this hall stands a throne. The king’s throne is always turned with its back to the interior of the hall until the King arrives: this, by the way, is an established custom in all embassies."

In general, the house’s decoration featured a lot of stone, as the owner was a Ural industrialist, and three styles coexisted here: Classicism, Renaissance, and Rococo. The interiors were worked on by architect Bosse and artist Viggi.

Demidov did not enjoy the house for long, into which he had invested considerable time and money. He died in 1840. The mansion was managed by his widow, who remarried a few years later—to Andrey Nikolaevich, son of the famous historian and writer Karamzin. Later, the house passed to Pavel Pavlovich Demidov—the son of Schernval and Pavel Demidov. However, he was not eager to live there. In 1864, he rented the mansion for nine years to the Italian embassy for 10,000 rubles per year (rumored to have lost it in cards), and later sold it to Princess Natalia Liven, granddaughter of the military governor of Saint Petersburg, who was involved in the assassination of Paul I. Under her ownership, the mansion underwent a kind of modernization: stoves were removed, and water heating, plumbing, and gas supply were installed. Additionally, Liven turned the mansion into a prayer house for Baptists, then abandoned it and moved to Livonia. It must be said that the idea of turning the mansion into a refuge for evangelicals was not liked by everyone.

From the memoirs of Sofia Liven (daughter of Natalia Liven): "After Vasily Alexandrovich Pashkov left, the meetings held in his house were moved to us at Bolshaya Morskaya, 43. Soon after, the Emperor’s General-Adjutant came to my mother with the message that His Imperial Majesty wished these meetings to cease. My mother, always concerned with the salvation of others’ souls, began by speaking to the general about his soul and the need to reconcile with God and gave him a Gospel. Then, in response to his message, she said: 'Ask His Imperial Majesty whom I should obey more: God or the Sovereign?' No answer followed this bold question. The meetings continued at our place as before. Later, my mother was told that the Sovereign said: 'She is a widow, leave her alone.' A few years ago, I heard from a reliable source about a plan to exile both my mother and Elizaveta Ivanovna Chertkova, but apparently Alexander III, not sharing the views of evangelical believers, as a God-fearing man, did not want to harm widows."

Interestingly, during all these pious meetings and charity bazaars that Liven held at her place, some visitors chipped off pieces of that very unique malachite.

In 1910, the building was purchased by the ambassador of the King of Italy (in connection with which the Demidov coat of arms was altered to resemble the Italian coat of arms), and in 1911 the embassy was housed in the building. The building stood empty for several years after the start of World War I, but after diplomatic relations were established between Mussolini’s government and the USSR, the building was returned to Italy, housing the embassy and later the general consulate (1924–1957). In 1918 (according to other sources, in 1925), embassy staff removed the malachite decoration—columns, pilasters, fireplace, as well as marble and parquet flooring; the removal was carried out through Crimea, and the decoration was lost.

In 1944, the mansion was transferred to the "Giprostank" institute. Eleven years later, the USSR began negotiations with Italy to purchase the building. The Italians did not sell the building but in 1957 signed an agreement with the Soviet government and handed over the mansion for use for 90 years—until December 31, 2046.

Sources:

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Доходный_дом_Демидова

Isaakievskaya Square, 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

1 Voznesensky Ave, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

Palace Square, 6, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Isaakievskaya Square, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

Yarmarochny Lane, 10, Nizhny Novgorod, Nizhny Novgorod Region, Russia, 603086

Bolshaya Morskaya St., 45, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000

Liflyandskaya St., 12, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 198099

5bis Imp. Marie Blanche, 75018 Paris, France

Isaakievskaya Square, 4, lit. A, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190000