Between 1945 and 1947, six public trials of German war criminals were held in the RSFSR in the most affected cities: Smolensk, Bryansk, Leningrad, Velikiye Luki, Sevastopol, and Novgorod.

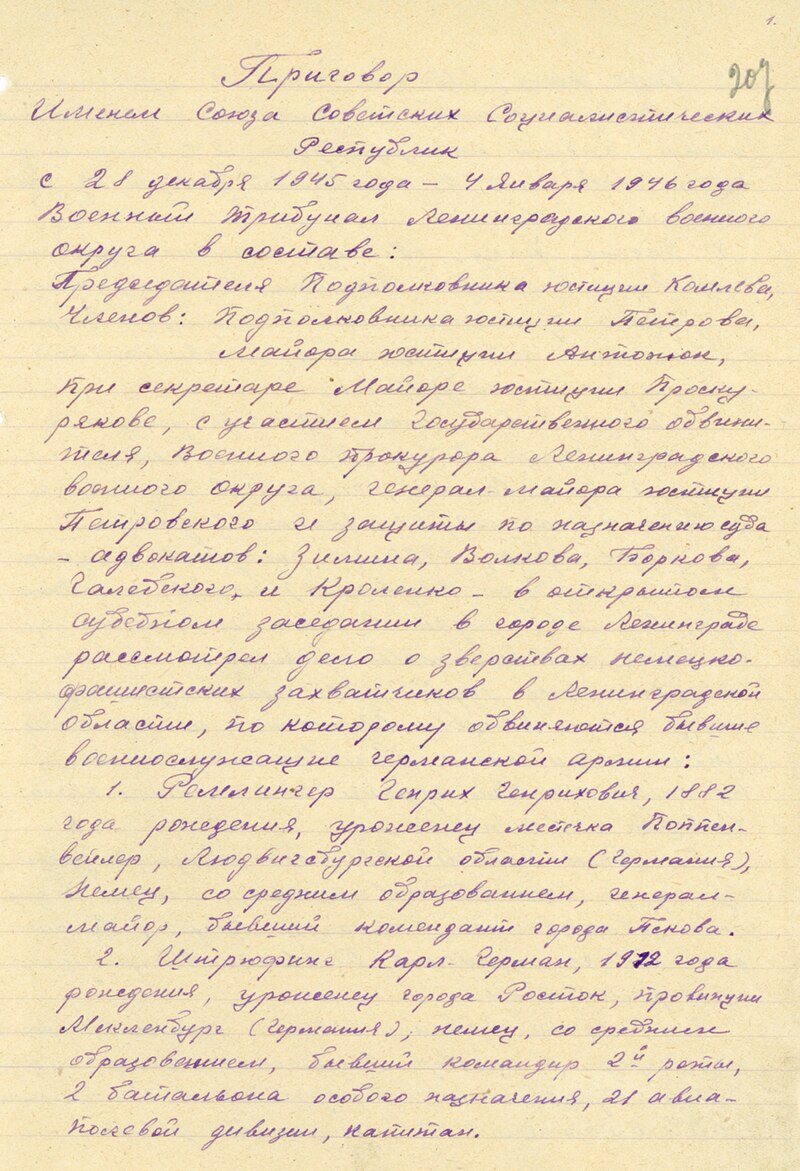

The materials of the Leningrad trial were classified (as were all other cases of similar trials) and are now kept in the central archive of the FSB of Russia. They are not released to researchers, just like other court cases of war criminals.

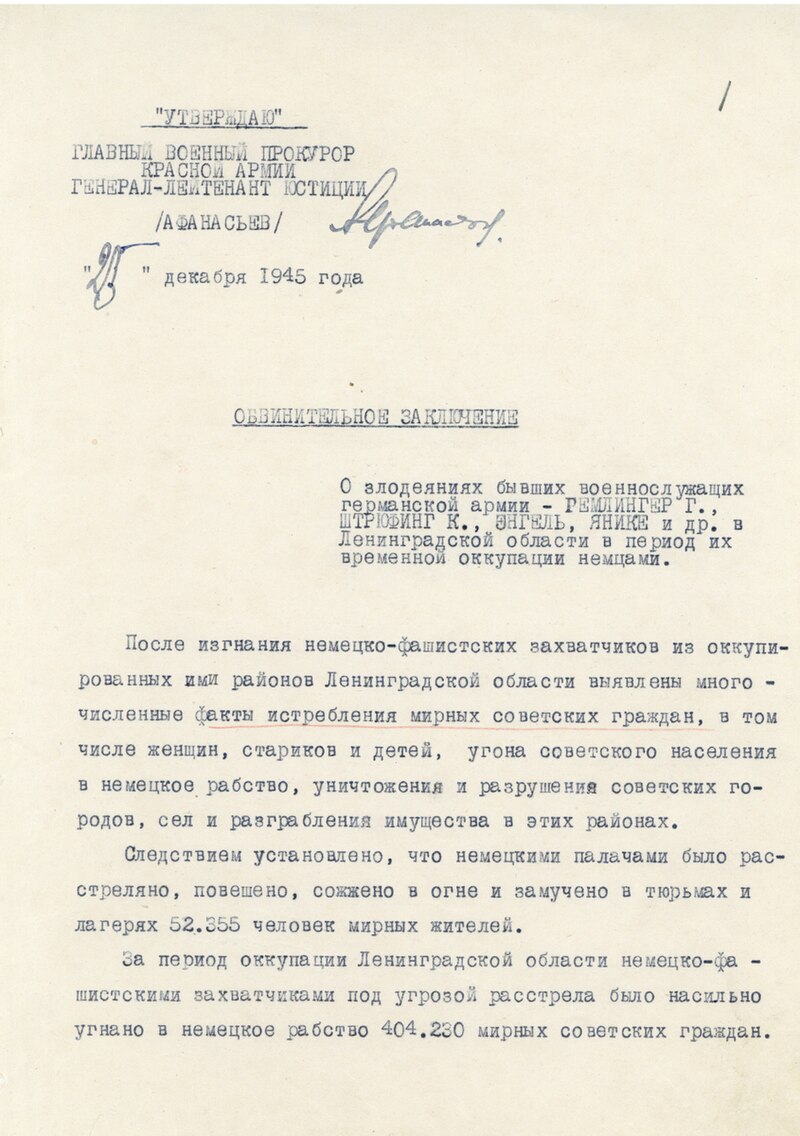

The NKGB, the Main Directorate of SMERSH, and the USSR Prosecutor’s Office were required to complete the investigation in just three weeks, “no later than December 15, 1945.” To assist in the preparation, organization, and conduct of the trial, a group of four operational officers from the NKVD, NKGB, and the Main Directorate of SMERSH, led by Major General Proshin, was sent from Moscow to Leningrad. Within such a short time, they managed to find only a few suspects in the German POW camps. It can be assumed that the rush in the investigation was caused by foreign policy reasons – the start of the Nuremberg Trials. Possibly, the materials of the local trials were meant to support the Soviet accusation at Nuremberg (including through foreign press). Recall that in February 1946, witnesses (academician I.A. Orbeli, Archpriest N.I. Lomakin, collective farmer Ya.G. Grigoriev) testified at Nuremberg about Nazi crimes in Leningrad and the Leningrad region (including Pskov and Novgorod).

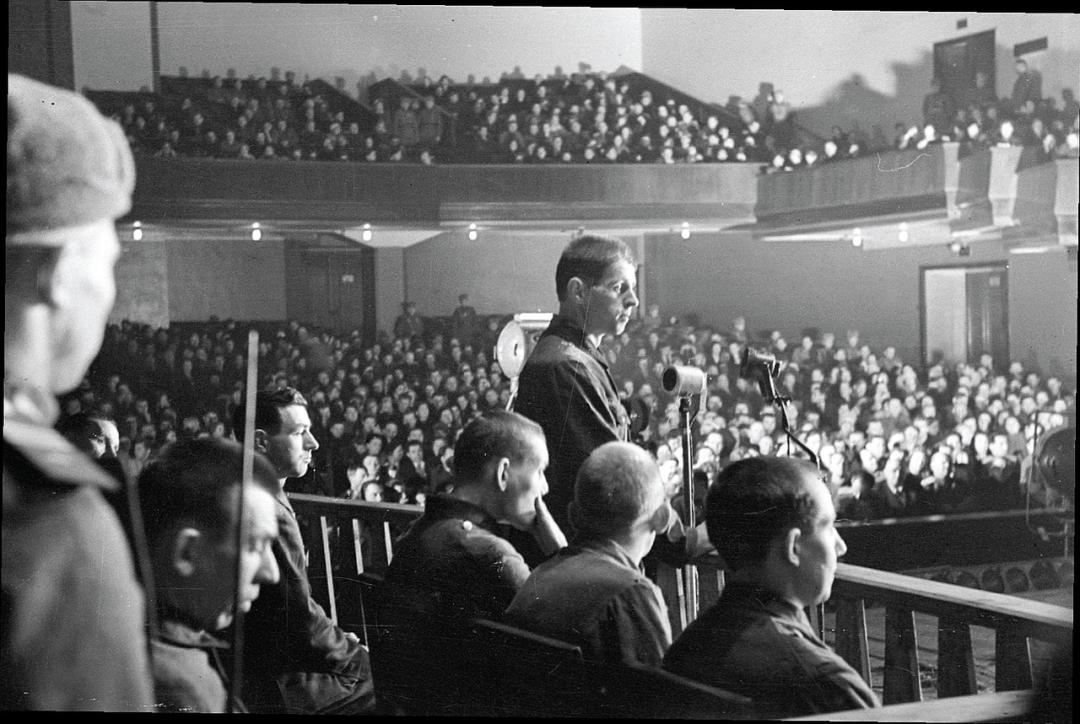

The Leningrad trial took place in the Vyborg House of Culture,

which accommodated 2,000 spectators from Leningrad, Pskov, and Novgorod (entry was by passes). The decorations resembled a theater: the tribunal of the Leningrad Military District was seated on a decorated stage, behind it stood a bas-relief model of the Kremlin and a large statue of Stalin on a pedestal; behind it was a screen for showing a documentary film, and before the sessions began, the curtain was raised. This theatricality was noted in his diary by writer and special military correspondent of TASS Pavel Luknitsky: Remlinger enters first, alone, goes behind a light wooden barrier. He scans the room with his eyes, struck by the solemnity, the light of the “Jupiters” (spotlights), the epaulettes, the entire atmosphere of the silent, packed hall. He pauses for a minute, uncertainly, timidly, like an actor, bows to the right and left... The theatricality enhanced the public impact of the trial.

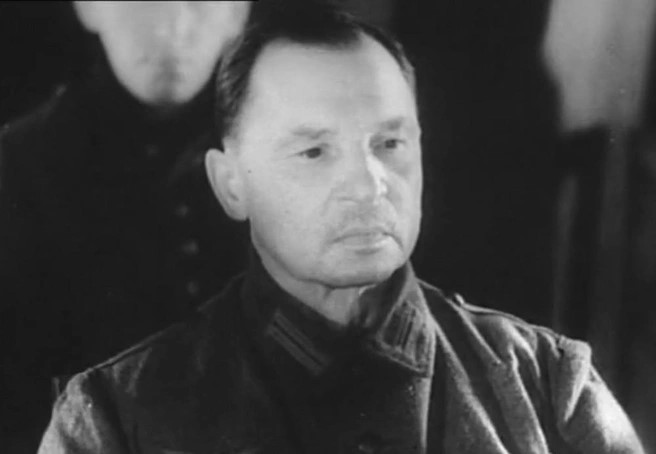

According to the Extraordinary State Commission (ChGK) data, which formed the basis of the accusation, the occupiers killed 52,355 civilians in the Leningrad region (which included Novgorod and Pskov territories) and deported 404,230 Soviet citizens for forced labor. The Nazis concealed their crimes, so the forensic medical expert of the Leningrad Military District, A.P. Vladimirskiy, believed that the number of “non-combat” deaths was much higher – up to half a million. According to his calculations, the main center of mass killings in the Leningrad region was Pskov. Possibly for this reason, the main defendant at the Leningrad trial was Major General Remlinger, the Pskov commandant in 1943–1944.

Henrich Remlinger

Source: frame from the documentary film “The People's Verdict” (1946, director L. Kikaz)

The trial examined the crimes committed by Remlinger and his subordinates in the Leningrad region during the winter of 1943–1944: punitive actions (executions, burning alive, torture), deportations for forced labor, destruction of settlements during retreat. Remlinger personally ordered several punitive expeditions, which resulted in thousands of Soviet citizens becoming victims (mostly women, children, and elderly). By Remlinger’s order, 25,000 people were deported for forced labor, and 145 villages were burned down.

Criminal orders for executions were also given by Captains K. Strüffing and Senior Lieutenant E. Wiese (commanders of the “special battalion” companies). Eight executors of these orders (sergeants and privates Beem, Engel, Sonnenfeld, Skotki, Yanike, Herer, Vogel, Dürré) served in the first and second battalions of the “special purpose” 21st Field Air Division. Lieutenant Sonnenfeld was the commander of the “special group” of the 322nd Infantry Regiment.

Each of the executors personally killed from 11 to 350 people and confessed to this at the trial. Only Remlinger and Wiese did not admit guilt. The defendants came to the “special purpose” battalions from the Torgau military prison, which was headed by Remlinger. Therefore, the prosecution and propaganda portrayed the defendants as Remlinger’s pupils: For six years Remlinger trained the people who came to him. Here they are, his pupils, sitting before the Tribunal on the same defendants’ bench as Remlinger. This is Yanike, the killer of more than three hundred Russian children, women, and elderly, an arsonist, robber, and sadist who burned innocent civilians alive. This is Skotki, who blew up dugouts with Russian families, burning village after village. This is Sonnenfeld, an engineer by education, who voluntarily became a Gestapo agent and then a leader of punitive raids on Pskov and Luzhsky villages.

There could have been more defendants from the “special battalion,” but some suspects actively cooperated with the investigation and were granted witness status, although they participated in the same actions. The Leningrad court used a collaborator as a witness against Remlinger – N.I. Serdyuk, an employee of the German commandant’s office in Kresty (near Pskov), testified about the inhumane conditions in the camp for civilians in Kresty. His participation was unusual, as the topic of collaborationism was censored, and all postwar trials against collaborators were held behind closed doors.

All crimes fell under the decree of April 19, 1943, which became the legal basis for all trials of foreign war criminals in the USSR. Additionally, the general part of the indictment included the destruction of cultural monuments in the suburbs of Leningrad, Pskov, and Novgorod.

Propaganda emphasized that the Leningrad trial concerned not only specific crimes of specific defendants in 1943–1944 but also the entire system of occupation of the Leningrad region from 1941 to 1944. Nevertheless, at the Leningrad trial (as well as at the Velikiye Luki and Novgorod trials), large-scale Nazi crimes committed in the Leningrad region against Jews, Roma, the mentally ill, and Soviet POWs were only marginally mentioned in some witness testimonies.

For example, ghettos were established and destroyed in the Pskov region in Pskov, Opochka, Nevel, Velikiye Luki, Porkhov, Pustoshka, and Sebezh. In autumn 1943, Jewish corpses were exhumed from pits and burned. No one was publicly held accountable for these Holocaust crimes. Remlinger (commandant of Opochka in July–September 1943) was not questioned at the Leningrad trial about the burning of Jewish bodies. In contrast to this silence, the prosecutor asked Remlinger about his position as military commandant of Budapest (from April 1944 until his capture in February 1945) and the executions of Hungarian Jews:

– Who was executed there?

– No one was executed.

– Jews, probably?

– Not a single Jew. On the contrary, I saved the lives of many Jews, you won’t believe it.

– Who executed them?

– Those who always did it, the SS, Gestapo, and others. I had nothing to do with them and, when I had the chance, saved Jews.

The execution of Hungarian Jews was not included in the indictment.

The forensic medical expert, Professor A.P. Vladimirskiy (who also testified at the Novgorod trial in 1947), gave detailed testimony about mass executions, describing many burial sites of victims, including Holocaust victims:

According to witness testimonies collected in the Moglino-Pervoye area near Pskov, somewhere there, in the Pskov region, in 1941, everyone in the camp was exterminated, and Jews brought from Pskov were also delivered there. Near Moglino-Pervoye, in a rye-sown field, ten mass graves filled with bodies were found: children, women, men. Since they were killed at the beginning of the war, the Germans did not undress people before killing them – they had not yet concealed traces of their crimes. Much was established by beads, amulets, and other items identifying the nationality of the victims. Then the Germans leveled the ground, turned it into a field, and sowed it...

Later, at the 1967 trial in Pskov, guards of the Moglino camp, ethnic Estonians, who shot Roma and Jews, were sentenced.

For the Nuremberg Tribunal, the Soviet side prepared two German witnesses on the topic of the Katyn massacre: Ludwig Schneider (assistant to Professor Butz) and soldier Arno Dürré (a defendant at the Leningrad trial). They were to support the Soviet version of the Katyn massacre.

According to Dürré’s testimony at the trial, the German command sent him from the Torgau military prison to corrective labor in the Katyn forest. Luknitsky conveys Dürré’s testimony as follows: In the military prison in Torgau, where until November 1941, during Remlinger’s tenure as prison commandant, Dürré was detained, he was “trained” in ruthlessness. The “practical exercises” during this training took place in the Katyn forest in September 1941. Along with others like him, Dürré was brought to this forest and dug huge burial trenches at night. SS men threw into these pits bodies brought by trucks – tens of thousands of Polish officers, Russian people, Jews, and Dürré participated in burying them.

– Can you roughly estimate how many executed people were thrown into these graves?

– From fifteen to twenty thousand people! – Dürré calmly replies and adds that he saw a photo of one of these graves in German newspapers, with the caption: “This was done by the Russians”...

Notably, the prosecutor did not ask Remlinger about these “practical exercises” in Katyn. Apparently, Remlinger did not want to cooperate.

Soviet propaganda conveyed the essence of Dürré’s answers but did not publish the absurd details: Dürré explained to the prosecutor that the Katyn forest is in Poland, that the enormous depth of the trench was 15–20 meters, that he reinforced the trench walls with tree branches for strength, etc.

All trials of 1945–1946, including the Leningrad trial, were reported to foreign journalists by Soviet propaganda. Among other things, a brief translation of Dürré’s testimony was published on January 3 in the newspaper “Die Tägliche Rundschau,” published by the Red Army for the German population in the Soviet occupation zone.

The Katyn topic was important for the foreign press, but Dürré’s testimony itself did not seem convincing. Ultimately, the “New York Times” combined in one note two versions of the Katyn tragedy – Dürré’s version as retold by TASS and the 1943 version from the Nazi Deutsches Nachrichtenbüro: Tonight TASS reported that a German officer among the defendants at the Leningrad trial, accused of “horrible crimes” during the war, admitted Nazi guilt in the Katyn massacre in the Smolensk region, where a mass grave of about 10,000 people was found. Previously, the Germans claimed that the Poles were killed by the Soviet political police and buried in Katyn in 1939. Describing in detail how retreating German troops killed Russian women, children, and elderly, an officer named Dürré stated that 15,000 to 20,000 people, including Polish officers and Jews, were executed and buried in the Katyn forest. In April 1943, the German news agency claimed that the Germans discovered the Katyn graves and blamed the Russians for this monstrous crime. Four days later, the Polish government in London announced it had appealed to the International Red Cross to send a delegation for an on-site investigation. On April 25, 1945, Moscow officially broke off relations with the government

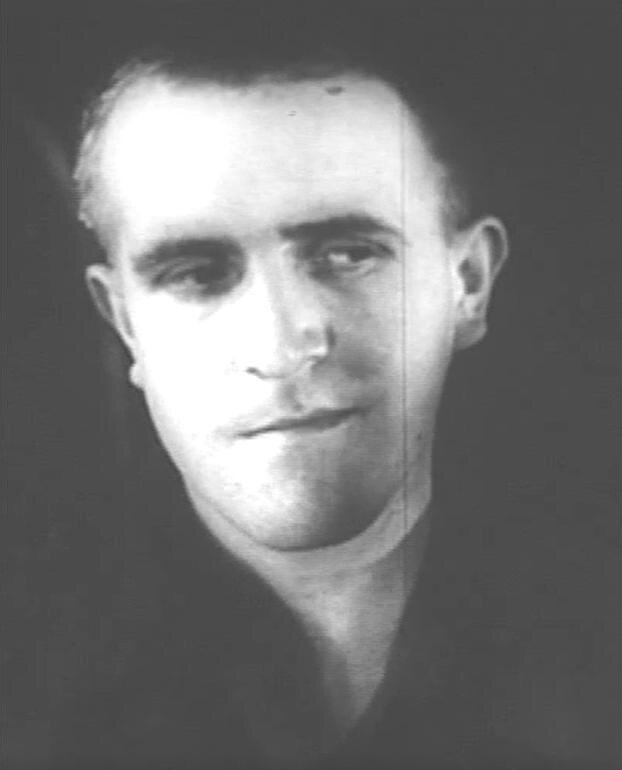

As Yazborovskaya claims, Dürré received penal servitude instead of the death penalty for this testimony, but Soviet authorities still did not dare to bring him to Nuremberg. This is unsurprising, as Dürré mocked the Leningrad trial and could have caused a scandal in Nuremberg. According to Luknitsky’s diary, Dürré laughed during interrogation (“when the topic of him shooting women came up, he nodded affirmatively and... smiled, laughed!..”), during the verdict (“Only Dürré smirks crookedly...”), and during his final words (“Dürré stands up, hands behind his back. Laughs! The hall waits. Dürré continues laughing and through laughter says: ‘I have nothing to say!’”)

Arno Dürré

Source: frame from the documentary film “The People's Verdict” (1946, director L. Kikaz)

In 1954, Dürré returned to the FRG, where he retracted his testimony about Katyn and stated that he was forced to say so during the investigation. Thus, the Katyn massacre topic is the only known case of false testimony at the Leningrad trial. Other defendants’ testimonies have not been disputed by researchers.

Propaganda used not only the defendants’ appearance but also biographical facts to dehumanize them, especially emphasizing their criminal past: Who are these representatives of the “master race”? Karl Strüffing and Fritz Enkel – volunteers of the German army who went to war for plunder and easy profit. Gerhard Yanike – a thief who served penal servitude. This group is fittingly crowned by Arno Dürré – a pimp who lived off prostitutes and robbed their clients.

According to instructions from Moscow, lawyers underwent special selection: “We propose... to thoroughly check the lawyers who will be assigned to defend the accused by the representative of the USSR People’s Commissariat of Justice on site. Undesirable candidates should be removed and replaced with vetted lawyers.” Thus, lawyers worked formally; no brilliant speeches or surprises were expected from them. Lawyers built their defense on diluting guilt – from individual to collective. For example, lawyer Zimin, defending Remlinger, noted that “for the horrific crimes committed by the Germans in the territory under the jurisdiction of the Pskov commandant, responsibility lies not only with his client. Units not under his command also operated here.” All other lawyers tried to portray their clients as mere executors of criminal orders.

The verdict was approved not in Leningrad but in Moscow. On January 3, 1946, the heads of the special services S.N. Kruglov, N.M. Rychkov, and V.S. Abakumov summarized the indictment in a two-page letter to V.M. Molotov

and proposed the sentence:

Considering the degree of guilt of each defendant, we consider it necessary to sentence defendants Remlinger, Strüffing, Sonnenfeld, Beem, Engel, Yanike, Skotki, Herer to death by hanging; defendants Vogel, Dürré, and Wiese to penal servitude. We await your instructions. Molotov approved all proposed.

Journalist M. Lanskoy vividly conveyed the feelings of people in the hall during the verdict announcement (death sentence for eight defendants, penal servitude for three):

Then the court entered. Everyone stood. There was an extraordinary silence as the chairman reminded once again of the atrocities committed by each accused. The shadows of the dead rose again from mass graves. The smell of fire smoke filled the air. The moans of the tortured were heard. A bloodied Russian mother stood up, holding out her executed child. The ashes of burned people settled in our hearts. Therefore, when the words “Death by hanging” were pronounced – applause of solidarity and satisfaction broke out. The people endorsed the verdict as final and not subject to appeal.

Some newspapers limited themselves to a dry statement of the verdict and the cliché about “applause of satisfaction.” The execution site in Leningrad was chosen as the large Kalinin Square near the “Giant” cinema. The execution itself was described in detail and emotionally by Leningrad newspapers: They escaped the just bullet of a Soviet soldier at the front. Now they had to test the strength of the Russian rope. Yesterday in Leningrad, eight war criminals were hanged on a sturdy crossbar. In their last moments, they again met the hateful eyes of the people. They again heard whistles and curses accompanying them to their shameful death. The vehicles moved. The last point of support slipped from under the condemned.

Tens of thousands of Leningraders came to watch the execution, and even more viewers saw it in the documentary film about the trial “The People's Verdict.”

Sources:

https://www.fontanka.ru/2020/11/20/69562288/

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ленинградский_судебный_процесс_над_немецкими_военными_преступниками

https://en.hpchsu.ru/upload/iblock/52d/52d6c6d6d4fdd24de88e91cf8d22bd17.pdf

Leningrad Trial of German War Criminals 1945–1946: Political Functions and Mediatization

Dmitry Yuryevich Astashkin, Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor, Senior Researcher

St. Petersburg Institute of History RAS (St. Petersburg, Russia)

ORCID 0000-0001-7840-4708

strider-da@ya.ru