W82X+P4, Danube, Primorsky Krai, Russia, 692891

In Chazhma Bay, near the cities of Vladivostok and Nakhodka, a terrible radiation accident occurred, which became known as the "Pacific Chernobyl."

The K-431 submarine of project 675 (with cruise missiles) was built in Komsomolsk-on-Amur in 1965. Over two decades, it completed seven autonomous voyages, covering more than 180,000 miles. A typical combat fate. At the pier of the ship repair plant in Chazhma Bay, qualified nuclear specialists and officers of the shore technical base were performing a scheduled refueling of the active zones of two "VM-A" type reactors (with a capacity of 72 MW) on the K-431 submarine.

During the operation to reload the "active zones" of the reactors of the Soviet submarine K-431, an uncontrolled chain nuclear reaction occurred, leading to a powerful explosion and the release of radioactive substances into the environment.

As a result of this accident, ten people died, and hundreds of others were exposed to severe radiation. The tragic events were caused by the actions of a boat moving through the bay at an excessively high speed.

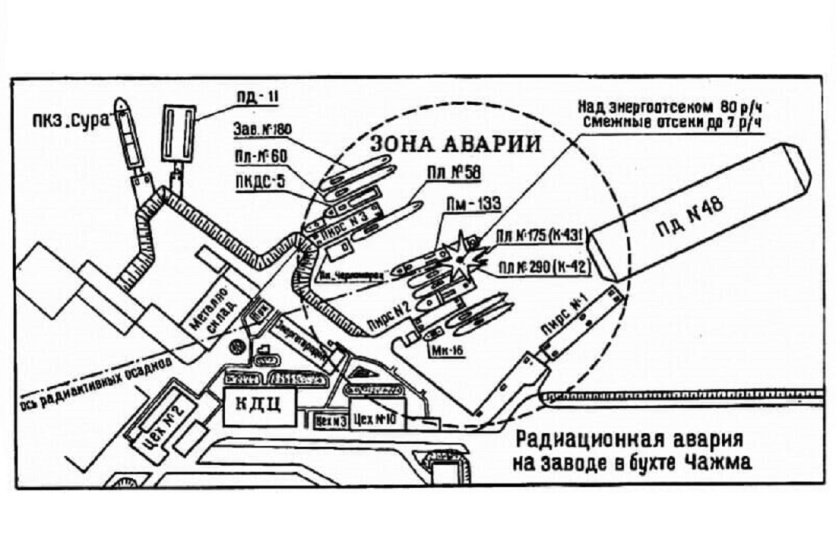

This is how the surface vessels were positioned in Chazhma Bay at the moment of the explosion. Diagram: personal archive of Sergey Yarantsev, a liquidator of the reactor explosion consequences, retired captain third rank.

In the summer of 1985, K-431, undergoing the procedure of replacing the active zones of the reactors, was sent to the ship repair plant. To successfully reload the two reactors, the shipowners invited a floating technical base. Experts from the ship repair base quickly began the necessary work on the K-431 submarine. Before starting the reload, the submarine’s readiness for this operation was thoroughly checked. To prevent unwanted situations, the reactor compartment was sealed, and the bulkhead doors leading to adjacent compartments were closed tightly.

From the outside (above the reactors), part of the superstructure was removed and part of the hull plating was taken off. The resulting open area was protected by an aluminum "winter" type shelter to guard against atmospheric effects, radiation, and to maintain the necessary temperatures in the reactor compartment. The first reactor was successfully reloaded and hermetically sealed. However, the second reactor encountered unforeseen problems. After completing the installation of fuel assemblies and mounting the red copper gasket on the reactor lid, tests for its tightness began. On the night of August 10, a leak was detected. It was found that a metal fragment from a welding electrode had gotten between the gasket and the reactor lid. This incident was reported to the management.

On Saturday morning, a commission was convened. Despite violating instructions, the commission decided to lift the reactor lid of K-431 and remove the fragment that interfered with the gasket’s tightness from the contact surface of the lid. To save time, the commission refused to secure the compensating grid with stops (a device to stop and fix movable parts of the mechanism), as this would have required cutting a knuckle (an angle bracket for rigidly connecting hull frame elements adjoining at an angle), which obstructed the reactor compartment. The officers also considered the danger of lifting the lid, which could cause the compensating grid to rise, potentially leading to an uncontrolled chain reaction in the nuclear fuel. They preliminarily calculated the safe height to which the lid could be raised.

Closer to noon, the process of lifting the reactor lid began using the bow crane of the floating workshop PM-133. Since PM-133 lacked special stabilization devices, its hull, like any other object on the water surface, was affected by waves. Under certain conditions, the waves would not pose a danger to the process, but in this case, they caused the catastrophe.

At the moment of lifting, despite the speed limit sign at the bay entrance, a torpedo boat (an auxiliary vessel, in this case a boat used to search for and recover practice torpedoes fired during exercises by ships and torpedo boats) sped through the bay at 12 knots. The resulting wave quickly reached the shore and caused the PM-133 to list (tilt sideways). Due to this list, the reactor lid, along with the compensating grid and control and emergency protection elements, rose temporarily higher than the calculations allowed. This led to an uncontrolled chain reaction, and at 12:05 local time, an explosion occurred.

The explosion caused the heavy reactor lid to be thrown high into the air and fall near the shore. Nuclear fuel and part of the reactor’s active zone were ejected into the environment as large fragments and aerosols.

Immediately after this, a severe fire broke out in the reactor compartment, accompanied by the release of dense acrid smoke. A crack about one and a half meters long and several centimeters wide appeared on the starboard side of the submarine.

The PM-133 base was also damaged by the explosion. The detonation tore off and threw the forward lifting crane into the bay. The PM-133 base was almost capsized, and a fragment of the vessel’s hull pierced the side above the waterline (the line where the calm water surface meets the hull of a floating vessel).

At the moment of the explosion, everyone in the K-431 reactor compartment died almost instantly. Later, when the remains of the deceased were found, due to the high radiation background, it was decided to cremate the remains directly on the plant’s territory, then place the ashes in ten containers and bury them in the ground.

A fire broke out in the K-431 vessel, specifically in the fragmented reactor section, releasing dangerous radioactive substances into the environment. The crew of the PM-133 vessel was the first to respond to the disaster and began extinguishing the fire. Firefighter sailors took turns approaching the reactor, fighting the flames using backpack fire extinguishers (extinguishers designed for water and aqueous solutions of non-aggressive pesticides), then returning to their ship to change gear. The firefighting boat PZhK-50’s team also participated in extinguishing the fire. While the fire fight continued, K-431 slowly began to submerge. Water, penetrating through the crack in the hull plating and leaks inside the reactor compartment, started spreading to other submarine compartments. The depth near the pier was 15 meters, so the submarine could easily become partially or fully submerged. It is not difficult to imagine the danger of radioactive contamination that would have threatened the bay and coastal areas if the damaged reactor had remained at such depth.

Before the reactor reload procedure on the K-431 submarine, shore power was connected. However, at the moment of the explosion, all cables supplying electricity to the vessel were severed. As a result, K-431 was left without power, and therefore, the use of standard means to dewater the submarine was impossible. Even if available, the pumps likely would not have had enough capacity for effective operation. In this difficult situation, the only correct solution was to try to push the damaged submarine onto a shoal.

One and a half hours after the explosion, the rescue tug "Mashuk" arrived at the scene. This vessel promptly moved PM-133, which was close to the accident site, to clear the way for rescue operations. It should be noted that the floating workshop crew spent about two days in a radioactive environment after the explosion to wash their vessel. Returning, "Mashuk" helped push K-431 onto a shoal closer to shore, which helped prevent the threat of sinking.

Work of the group extracting fragments of the bodies of deceased servicemen. Sergey Yarantsev is at the bow of the lifeboat. Photo: personal archive of Sergey Yarantsev.

Later, to completely remove the remaining water from the submarine, two floating cranes with lifting capacities of 500 and 2000 tons respectively were brought in. They lifted the stern of the submarine above the water level, allowing successful dewatering. Despite all the rescuers’ efforts, radioactive contamination around the K-431 explosion site was noticeable. In the immediate vicinity of the emergency, according to participants in the aftermath liquidation, standard dosimeters showed critically high readings. Seven and a half hours after the explosion, the radiation background in the accident area reached 250–500 microsieverts per hour (the safe level of external human body exposure is up to 20 microsieverts per hour. The upper permissible dose rate limit is 50 µR/h).

Ultimately, the liquidators managed to clean almost all areas heavily contaminated with radioactive dust and debris at the plant and nearby territory. Where human efforts were insufficient, mechanical methods were used. Bulldozers removed the topsoil layers and transported them to special landfills.

Significant radiation doses were received by 290 people; ten were diagnosed with acute radiation sickness, and 39 with radiation reaction. All victims were saved, but by the mid-1990s, the officially identified death toll exceeded 950 people. Many radiation-related diseases manifested years later. The highly radioactive remains of the deceased sailors were buried at Cape Sysoev at great depth under a thick layer of concrete. The damaged submarine was towed to Pavlovsky Bay after the reactor was filled with concrete.

The geographical features of the area prevented a more extensive catastrophe. The slopes of the surrounding hills localized the spread of the radioactive cloud, and on the evening of August 10, a heavy downpour washed radioactive dust to the ground. The coastal settlement of Dunay and other populated areas suffered significantly less than they might have under different weather conditions. The nuclear accident in Chazhma was classified for eight years. Even after declassification, information was only circulated within the Ministry of Defense, meaning extremely limited access for victims to compensation and medical care. Many liquidators were never able to prove a causal link between their illnesses and participation in the accident cleanup.

The tragedy in Chazhma Bay became a kind of warning that the USSR authorities preferred to hide from their own people. Less than a year later, the Chernobyl disaster occurred—of a completely different scale, which could not be concealed.

Only in 2016, 31 years after the accident, was the K-431 submarine finally decided to be disposed of. The impetus was the preparation for the APEC 2012 forum, when Primorye was to be cleared of radioactive scrap metal. "How long it could stay afloat is hard to judge. The main ballast tanks had rusted through. After the explosion, there was a crack in the hull. The submarine was held afloat by pontoons," said Andrey Rossomakhin, General Director of DVZ "Zvezda."

Submarine K-431 in the dock of the "Zvezda" plant, 2010. Photo: Alexey Sukonkin.

At the plant in the settlement of Dunay, where the explosion occurred, they refused to dismantle the submarine. It was towed to Bolshoy Kamen, where unprecedented preparatory work was carried out: part of the hull was dismantled, structures were decontaminated. The damaged reactor and adjacent compartments were cut out, sealed, and sent to a special sarcophagus for burial at the isolation point for emergency submarines.

The tragedy in Chazhma Bay remains a little-known chapter of Soviet nuclear history. It also became a harbinger of the terrible accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant: negligence and loss of fear of the atom cost a huge number of lives.

Source:

https://ab-dpo.ru/portal/cs-articles/radiatsionnaya-avariya-v-bukhte-chazhma-10-avgusta-1985-goda/

https://propb.ru/calendar/radiatsionnaya-avariya-v-bukhte-chazhma-10-avgusta-1985-g/

https://fedpress.ru/article/3393958

Courage Square, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 194021

Sennaya Square, Sennaya Sq., Saint Petersburg, Russia

Skipper's Quay, 16-18, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199106

Spassky Lane, 14/35, BC Na Sennoy, 3rd floor, office A320, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190031