Zhukovskogo St., 7, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191014

“July 1915. The most joyful date. I meet L.Yu. and O.M. Briks,” Mayakovsky recorded many years later in his autobiography. Elsa Triol, Lilya Brik’s sister, recalls: “Mayakovsky came to visit me at Lilya’s, on Zhukovsky Street. Whether it was the first time or another meeting, I persuaded Volodya to read his poems to the Briks, and I think that evening the fate of many who listened to Mayakovsky’s ‘Cloud’ was already being shaped... The Briks reacted to the poems enthusiastically, fell irrevocably in love with them. Mayakovsky irrevocably fell in love with Lilya.”

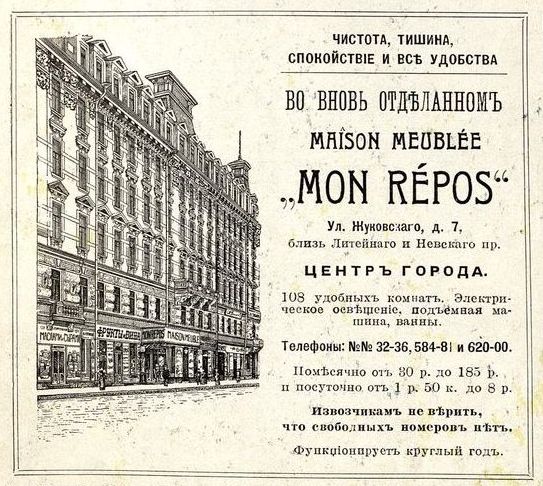

The Briks lived on Zhukovsky Street. The large six-story building No. 7/9 belonged to Glikeria Grigorievna Kompaneyskaya, a hereditary noblewoman, wife of a sworn attorney (“All Petersburg” for 1915). Apartment No. 42, rented by the Briks who had recently arrived in Petrograd, was located on the top floor of the courtyard wing but also had a main entrance from the street. The apartment consisted of three small rooms with windows facing the courtyard, a spacious square hallway, and a long corridor at the end of which was the kitchen.

Osip Brik decided to organize a reading of the poem “The Thirteenth Apostle” at his apartment. On the appointed day (the second half of July 1915), Mayakovsky again approached the Briks’ house: today the fate of his poem would be decided! As if in tune with his mood, a tram loudly and cheerfully screeches on the rails at a sharp turn from Liteyny Prospect, and seemingly grinning in a smile, looks at him from the wall — the “mare’s head molded” later immortalized in the poem “The Man”:

“The lanterns were also embedded

in the middle of the street,

The houses look alike.

Just like that,

from a niche,

the mare’s head

molded.

- Passerby!

Is this Zhukovsky Street?”

Quickly stepping over several steps, Mayakovsky ascended the front staircase, richly decorated with stucco. But it was clear that here, just like on the city streets, cleaning had not been done for a long time: all sorts of litter, cigarette butts, sunflower seed husks. The elevator cabin hung motionless in its ornate cage. War. It had touched everything...

In Lilya Brik’s memoirs, there is a detailed account of Mayakovsky’s reading and the impression he and his poem made on the listeners.

“The Petrograd apartment was tiny. Between two rooms — the dining room and the so-called study — the door was removed to save space. Mayakovsky stood leaning against the door frame. ‘Cloud...’ was neatly handwritten into a notebook. He read it by heart but held the notebook in his hands. This was what they had long dreamed of, what they had waited for. Recently, no one wanted to read anything. All poetry seemed worthless — the wrong people wrote, and not like that, and not about that — but here suddenly it was like that, and about that.”

Learning about Mayakovsky’s unsuccessful attempts to find a publisher for the poem, Osip Brik decided to publish it at his own expense, gave Mayakovsky the first payment, and agreed to publish all his works in the future, paying 50 kopecks per line.

The new year 1916 was approaching. Vasily Kamensky arrived in Petrograd. Their meeting with Mayakovsky was joyful and heartfelt. The poet invited Kamensky to celebrate the New Year with the Briks, where only close friends would gather.

...The small apartment on Zhukovsky was tightly furnished, with a wide sofa, armchairs, and a grand piano occupying a significant part of the largest room. On the wall, in a prominent place, was a shelf with books by futurist poets. Above the sofa hung a large portrait of the hostess of the house, painted by Grigoriev, a student of Repin.

The New Year’s Eve at the Briks’ was cheerful and relaxed. Lilya and her sister greeted guests and bustled about. Mayakovsky decorated a Christmas tree suspended from the ceiling. The decoration was as unusual as its location: instead of sparkling balls, cones, and golden tinsel, yellow paper sweaters and matching black pants with tufts of cotton stuck out hung on the green branches... The merry, lively guests dressed in masquerade costumes sat down for the New Year’s dinner. It was clear the hostesses had made an effort. Despite the difficulties of wartime, the table was “luxurious”! Even pink jam! Where from? Volodya brought it. Kamensky, chosen as toastmaster, amused everyone all evening. Dressed as a stargazer with painted-on mustaches, he predicted everyone’s fate: with a serious face, he spoke funny and cheerful nonsense. They started a game of forfeits, and to the delight of those gathered, Mayakovsky managed to “recite his favorite work.” Without getting up from his chair, he read Pushkin’s “The Bronze Horseman” from beginning to end.

The poet in love wanted to be closer to his muse — Lilya Brik. Living on Nadezhdinskaya, Vladimir had the opportunity to visit Lilya often, whose home was nearby on Zhukovsky Street.

Soon, deeply in love, Vladimir found this was not enough. Soon he moved to live at Zhukovsky Street, 7. As is known, his muse was married. One might think a dilemma should arise. Lilya, after many years of life with Osip, was very attached to him and did not want to break her marital happiness suddenly, but she already loved Vladimir strongly and passionately. Osip still had deep feelings for his wife and did not want to break up. The poet was ready for anything for the great love he truly felt in his heart, as his entire life proved. He moved into the Briks’ apartment, where a real ménage à trois began — “l’amour de trois,” which in French means “love of three.”

This was a real trial for the poet. Lilya did not spare the feelings of the enamored Mayakovsky, believing that through his suffering he wrote good poems. Later, Brik admitted in her memoirs that she liked it when the poet was at home, locking himself in a room with Osa and making love so that Mayakovsky could hear. At first, the poet scratched at the door and tried to break it down, then in despair ran to the corner of Nevsky Prospect and the Fontanka embankment, where he walked all night. The futurist wrote about his torment in the poem “The Flute-Spine.”

“I’ll just fall flat on my back now

and bruise my head on stony Nevsky!

But instead, until early dawn

in horror that they took you away to love,

I tossed and turned

and carved screams into lines,

already half-mad jeweler.”

It is worth saying that in this life, nothing is new. There have been and still are many examples of “threesomes” in domestic and foreign love history, mostly among creative people.

In early December 1917, Mayakovsky left for Moscow, where literary performances and film work awaited him. Returning to Petrograd in mid-June 1918, he again settled in house No. 7 on Zhukovsky Street. The “Book for recording arrivals and departures at house No. 7 on Zhukovsky Street” has been preserved, in which under No. 35 is listed: “Mayakovsky Vladimir Vladimirovich. Citizen of the Russian Republic,” with him — “certificate of the Petrograd police of the 3rd Liteyny district dated November 27, 1917, No. 22020.” Mayakovsky was registered in the said house from June 18, 1918, to May 6, 1919. In 1915, he lived in this house without any registration.

Sources:

https://peterburg.center/ln/marshrut-po-sledam-mayakovskogo-v-peterburge.html

https://www.citywalls.ru/house7693.html

http://majakovsky.ru/mesta/zhukovskogo-d-7/

Liteyny Ave., 46, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191014

52 Mayakovskogo St., Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191014

Pod"ezdnoy Lane, 4, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 190013

Gatchinskaya St., 1, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 197136

pl. Iskusstv, 5, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

Chkalova St, 8, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 194361

Mokhovaya St., 33, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191028