Agrastų St. 15A, 02243 Vilnius, Lithuania

At a distance of 8 km, near the city of Vilnius, in a forested area by the highway towards Alitus Hill, there used to be a resort. But since 1940, work was carried out there to create a fuel storage facility for a nearby Soviet military unit. There was also a railway nearby with a station of the same name. However, construction was not completed due to the start of the German invasion of Lithuania. The huge round pits that had been dug, into which fuel tanks were not delivered in time, remained empty. On this territory, covering 48,608 square meters, in seven deep round pits and three elongated trenches, from July 11, 1941, to July 5, 1944, 100,000 people of different genders and ages were shot and tortured to death; among them, 70,000 were Jews, and 30,000 were Roma, Poles, and Soviet prisoners of war. The site was fenced with barbed wire and guarded by Lithuanian police. Even many Germans were forbidden entry.

Executions had taken place here before, but not on such a massive scale. It was from July 11 that Polish journalist Kazimir Sakovich began writing his diary from the attic of his home, which he later buried in his yard. In it, he recorded the executions at Ponary from that day until October 6, 1943. The shootings were carried out by the 3rd company of the 3rd battalion, members of the “Flying Squad of Haman,” and others. Witness Stanislav Stepanovich Seynyuts confirmed that from July, Lithuanians drove columns of men, women, and children of Jewish nationality to Ponary, who were beaten and exhausted by the journey. They also carried the bodies of those who had been killed or could not endure the journey and were shot by the escorts along the way. Gunshots were heard for a long time, as confirmed by many local residents. The columns of escorted people constantly increased by September, sometimes brought in by trucks. The columns were arranged in groups of 5–6 people, with women and children holding hands at the front, and men walking last, with their arms resting on their shoulders.

Later, from about April 5, 1943, people began to be brought by trains and unloaded at Ponary station, which meant that the nearest victims had already been exterminated and they started bringing victims from more distant areas. Judging by the number of bodies after unloading the first arriving train, which had up to 49 wagons, one can imagine the crimes committed. People could be shot indiscriminately, beaten, and subjected to any atrocities. For example, there are descriptions of a case where a small boy’s head was cut off and then used to play football. Bodies at the station were not removed for several days. About 2,500 people were killed from this one train between 7:00 and 11:00, i.e., in 4 hours.

During the shootings, there were also mass escapes in panic when people saw the execution pits filled with bodies, understood everything, and ran in different directions, while Lithuanian shooters and Nazis began shooting at them. When groups were brought in several people at a time, they were laid on the ground about 35 meters from the pit, then 6–10 people were led to the edge of the pit. There they were ordered to undress, turned to face the pit, and shot in the back of the head. If a person was wounded, they were buried alive. The executed were buried by the Jews themselves. All Jews who arrived at Ponary were told they were being taken or led to work, which calmed people who understood this was a deception near the pits themselves. People were shot in groups of 250–300 per day, often simultaneously in several pits.

Throughout this time, there was trade in the belongings of the murdered Jews with local residents. Shooters were allowed to take only clothing; valuables were taken by the SS who oversaw the executions. The flea market was also an attraction full of surprises. In the belongings, one could find sewn-in money and jewelry. There were even more cynical moments. Local residents ordered specific items from the shooters, such as shoes, suitcases, and children’s things. Horrifyingly, resellers and peasants who bought clothes from the shooters ordered specific sizes, and could even select a desired item on a living person when Jews were led past. For a certain payment, the shooters would bring or exchange these items for alcohol. There were cases of fraud: for example, a sack was sold by weight in exchange for vodka, but when the buyer opened it, among the items was a child’s corpse that weighed down the sack. The buyer buried the body in the forest. Many items were sold in Vilnius. Naturally, there was someone who could hardly be called a mere reseller; people brought him the belongings of the murdered, which he sold at the market. His name was Yankovsky. He lived nearby by the highway. It could be said that the people of Vilnius dressed in Ponary. How widespread the trade was is unknown, but judging by the scale of the executions, it was a major commodity in the market.

Since the Nazis controlled this extermination center, the belongings of the murdered also passed through them. However, Lithuanians, like the younger Nazis, organized secret removal of valuables, secretly transporting them at night on the trucks that brought the victims. The SS found some of the hidden items, but not all. Needless to say, criminal organizations were involved.

To increase the speed of executions, machine guns were used; people were pushed into the pit and shot from above, sometimes grenades were thrown in. “Mercy” was also practiced: some had their eyes blindfolded at their request. Lithuanian shooters or SS men often raped women they liked. When children were found in clothing or bundles, they were also taken to the pit and killed there. Sometimes two trees were bent, both legs tied to different ends, and then released. There were also utterly monstrous murders. Pregnant women had their abdomens cut open and the fetus removed, with the killers saying: “Well, let’s see if you would have had a boy or a girl?”

Sometimes people managed to escape and sought refuge in villages, but local residents either handed them over to the shooters or killed them themselves. Captured escapees were tortured for a long time in front of passersby. Some Jews, to save themselves, gave all their valuables to the escorts in exchange for a promise of release, but the escorts always deceived them after taking the money. There was a case when a woman, overwhelmed with horror, could not force herself to go to the pits. She begged an SS man to release her with her children, but the shooter simply grabbed one of her children and threw him over the fence. She ran after him, running around the fence, trying to protect her son. This became a regular occurrence: women were shot together with their children, and the mothers themselves undressed them. If a woman refused to go, even after brutal beatings, one of the shooters would approach, grab the child, and throw it into the pit; the mother would rush after the child into the pit, a volley would sound, and then the next victims would be lined up. There were cases when, to save bullets, children were killed with rifle butts, or to avoid shooting each one, they were thrown into the pit and buried alive. Not everyone was undressed. People and children were sorted by the condition of their clothes. Those better off and in new clothes were undressed, while the poorer in old clothes were shot immediately. Sometimes people resignedly went to the pit themselves and sat or stood near it, making the shooters’ work easier. When bodies accumulated at the edge of the pit, the process was stopped, and an SS man ordered several Jewish men to climb into the pit and arrange the bodies, after which he gave the command and they were killed. Jewish men were also forced to collect the bodies of those killed or who died on the way and drag them into the pits.

At Ponary, not only Jews were shot, but also captured Red Army soldiers, underground fighters after Gestapo torture. Prisoners from Lukishki prison were also brought and shot here. There was no permanent team of shooters at Ponary; those who brought prisoners or were assigned, such as the 3rd company, carried out the shootings. Only permanent guards, Lithuanians from the SD, and the command staff from the SS and SD were present.

On September 23, 1943, the Vilnius Ghetto was destroyed; before that, all 4,000 people, including prisoners from the Švenčionys ghetto and several small ghettos in the Vilnius area, had been killed at Ponary.

In March 1942, SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich ordered SS Standartenführer Paul Blobel, commander of Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe “C,” to begin destroying the traces of executions at all sites where they had been carried out, whether concentration camps or execution pits. Since the Nazis kept detailed records of the killed, the locations and number of mass graves were precisely known to them. Instructions stated that bodies from execution pits must be dug up and burned, and the bones that remained were to be crushed and scattered or thrown back into the pit. If it was impossible to burn the bodies, the decomposition process was to be accelerated, for example by mixing with lime. There is only one explanation for why this was necessary. When Reichsführer SS Himmler visited the death factory Treblinka II, he saw piles of corpses and ordered them to be burned. Blobel began the operation to destroy traces at the end of June 1943; the order was given by SS Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller, who was assigned to Eichmann’s department IV B4 “Jewish Question.” The operation was called “1005,” given the highest secrecy level. Later, in concentration camps, bodies were burned. At old execution sites, bodies were dug up and burned on pyres. The organization was structured so that SS men commanded, guards—usually Ukrainians—provided security and control, and workers, mostly prisoners of war or Jews from the nearest concentration camp, dug up bodies from graves and burned them. At the end, the guards killed the workers, and the SS killed the guards. All reports on “1005” were coded with prearranged words, for example, the places of execution were called “Leveling” (Trostenets), “Pacification” (Grodno), “Secret Nature” (Orsha and Borisov), “Weather Report” (Rogachev). By 1944, the main work was completed. But the killing of people continued until 1945 and stopped only with the liberation of the camps. Most likely, the reason was that Himmler, seeing that the murder of the Reich’s enemies was the responsibility only of the SS and not Hitler, and even Göring, who was the first supporter of extermination as a method of solving problems, did not want to hear about it. Therefore, Himmler was personally responsible and possibly began to fear that sooner or later this would be used against him. He tried to reduce or stop the killing of Jews in concentration camps to try to negotiate with the Americans and British but could not control the SS, who continued killing.

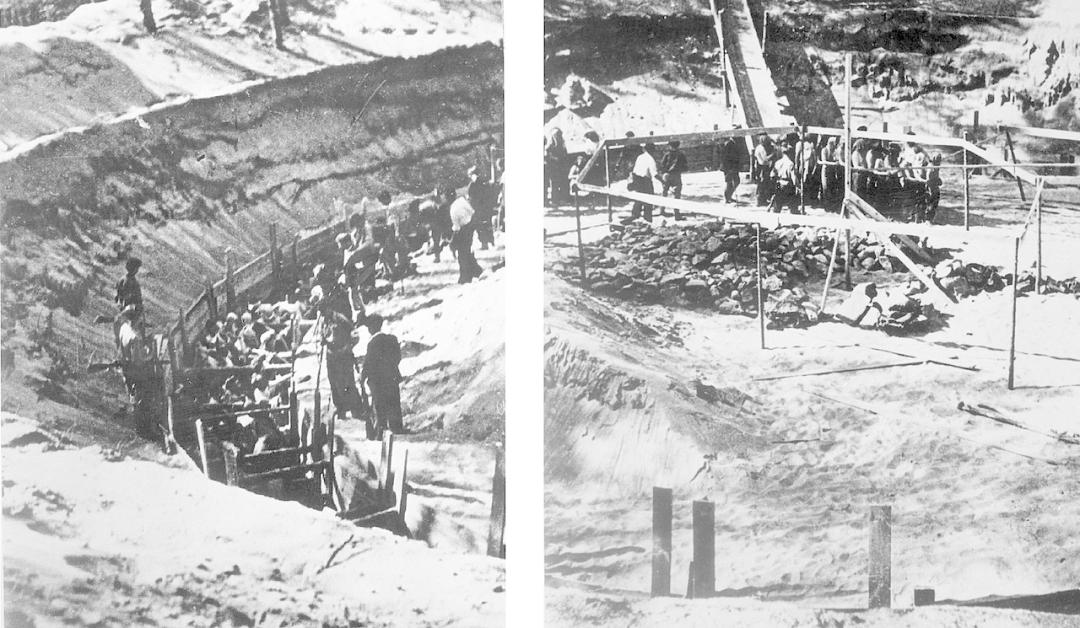

From June 1943, at Ponary, as everywhere mass killings took place, bodies were dug out of graves and piled into huge pyres. Workers—arrested Lithuanians, Jews, and captured Red Army soldiers—were brought from prisons and camps for this purpose. The complex where executions were carried out was fenced with wire and surrounded by minefields. Barracks for workers were built at the bottom of the execution pits, which were huge craters with pits dug around the edges where the bodies lay. In the center, at the bottom, a pyre was stacked on which bodies were burned. In other areas, pyres were stacked at the top, and workers descended into the pit via a ramp and carried bodies up. Work continued until the liberation of Vilnius on August 5, 1944. At the top of the pit, on both sides, there were ladders in the form of ramps, which were always raised and lowered only when necessary. There were two ladders due to racial prejudices: one for workers, the lower caste, and the other for SS men who supervised the work. Workers were not allowed to touch the ladder under penalty of death. Workers wore chains. For any minor violation or delay during work, they were brutally beaten, and for any offense, killed. The sick were also killed. If a person fell ill, they were classified as sick and sent upstairs to the “infirmary.” They went upstairs, were taken aside, and killed. The shot was heard, so workers did everything to avoid suspicion that they were ill. Sometimes someone from the workers’ team was appointed to the “infirmary” like a roulette. Often candidates were intellectuals or students.

The work consisted of two parts: the pits from which bodies of executed people were taken, and the pyres on which bodies were burned. In the fascists’ lexicon, bodies were called “figures.” They were dug up, hooked, and pulled out from the mass. They were placed on stretchers and carried to the pyre. There they were inspected for hidden valuables. Many were shot in clothes, or people, not knowing where they were going, hid various valuables sewn into their underwear, but they were often killed in their underwear, although most were naked. The pyre was made of crosswise spruce branches on which bodies were laid, doused with gasoline, and covered with spruce branches. Up to 3,500 bodies were stacked, surrounded by termite tablets, and set on fire. The pyres burned for three days. The remaining bones after burning were ground to powder. The powder was sifted through screens and poured back into the pits from which the bodies were taken. Found valuables or other items buried with the dead were supposed to be handed over to the guards, but some workers managed to hide things for themselves. Everything was done to conceal the traces of mass murders. This was not hidden. Sturmführer Schroeder, responsible for the burning, said:

“Enemy propaganda spreads rumors that 80,000 were shot at Ponary. Nonsense! Let them search in a couple of months, whoever wants and however they want, they will not find a single figure here.”

At the same time, mass shootings continued during the burning of bodies from old graves. This process of mass shooting was called “Execution” by the Nazis. The difference was that freshly killed bodies were laid on the pyre immediately. As of April 15, 1944, 80 people worked at Ponary. Seventy-six men worked on destroying bodies, and four women prepared food, carried water, and firewood. About 50 people were prisoners of the Vilnius Gestapo, 15 from the provincial town of Žiežmariai, and 15 Soviet prisoners of war. The guards were Germans from SS units (more than 50 people). The work was supervised by Gestapo officers from the SD department, headed by Sturmführer Schroeder. Some of the workers were Jews who escaped execution because the Nazis, according to Himmler’s order on labor force, left a certain number of Jews alive for work. Those who ended up at Ponary found the bodies of their relatives and loved ones during the burning. Working in filth, in inhuman conditions, knee-deep in rotting human remains, these people burned thousands and thousands of bodies every day. As with the entire “Operation 1005,” there were to be no witnesses, so the SS often told the workers phrases like: “Whoever says anything—there are no witnesses and there won’t be any,” “There is a road to Ponary, but from Ponary—there is none,” and the leitmotif: “No one left Ponary and no one will.” The workers understood that they would be the last clients on the pyre. Because of this, they began digging a tunnel for escape under their hut up to the wire fence. The tunnel was about 30 meters long. Digging was dangerous; there was sand all around, and the passage often collapsed, burying the worker. They dug him out, pulled out the body, and continued digging. The risk of being discovered due to betrayal or by the SS was very high, but hatred and the desire for revenge, to tell about Ponary, were stronger than fear and disagreements. They even installed lighting in the tunnel from stolen or found wire and two light bulbs. On April 12, 1944, the tunnel to freedom was completed. Waiting for deep night, on April 15, 1944, 80 people crawled out of the tunnel and crawled toward the forest. They were noticed, shooting began, but 30 managed to escape. They were pre-divided into groups, and some managed to reach partisan units.

During the entire occupation of Lithuania, according to the International Commission, up to 206,000 people of different genders and ages were killed. Among them were about 190,000 Lithuanian Jews; about 10,000 Jewish refugees from Poland; about 5,000 Jews from Austria and Germany; and 878 French Jews. As a result of the joint activities of all nationalist punitive formations in Lithuania, almost all Jews in Lithuania were exterminated.

Sources:

https://document.wikireading.ru/h6afFBZpyx

http://holocaustatlas.lt/EN/#a_atlas/search//page/9/item/34/

https://kvr.kpd.lt/#/static-heritage-detail/0e64f8ee-a8b8-4b0e-8eea-a00f67f26713