877C+P63, Sharof Rashidov Shoh Street, Tashkent, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

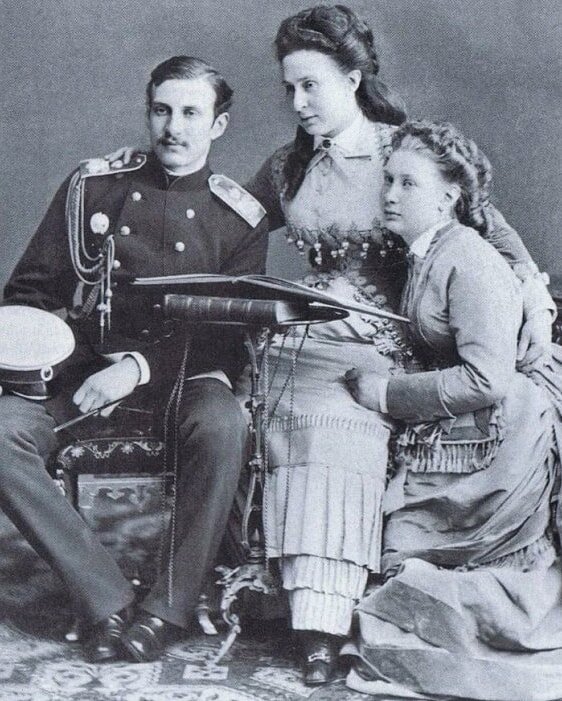

The youthful years of the prince — grandson of the Russian Emperor Nicholas I — were not only carefree but also promised him a promising future. Nikolai Konstantinovich was born into the family of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich. In the family, he was called Nikola and considered the most handsome among the children and grandchildren of Nicholas I. He possessed a sharp mind and became the most successful graduate of the Military Academy of the General Staff from the House of Romanov, finishing with a silver medal. His career began with joining the Life Guards Horse Regiment, where he became a squadron commander. The Grand Duke was a passionate traveler, collector of art and antiques. When he first arrived in Turkestan in 1883 as part of the Khivan campaign, he was captivated by the atmosphere of the East, the fortresses of Khorezm and Ichan Kala combined with the boundless deserts, memories of which he brought back in the form of several paintings, books, and cast-iron figurines. For his courage and heroism during the campaign — the resistance was fierce — he was awarded the Order of St. Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duke Vladimir.

The reason for the appearance of a member of the imperial family in a distant southern city was a scandalous story from 1874. It was a tradition at the Winter Palace to hold family evenings when the closest relatives of the tsar gathered for dinners held in the chambers of Empress Maria Alexandrovna. One time, after such a meal, the empress said goodbye to the guests, sat down to write letters, and suddenly discovered the disappearance of her favorite seal — a gem made from a solid smoky topaz. They didn’t know what to think — only family members were in the chambers. After the next family dinner, a relic disappeared from the chambers — a porcelain "opaque" cup with a Chinese pattern, which Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, ordered on the day of his coronation. In 1721, in honor of the victorious end of the Northern War, Augustus gifted it to Peter I.

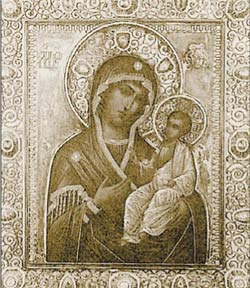

The loss at the next family meal was a pencil in a gold case with a large ruby on the tip. At this point, a delicate but thorough investigation began. Meanwhile, the thefts continued — after the wedding of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna and the Duke of Edinburgh, emerald earrings of Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna disappeared from the Marble Palace. The places where the thefts occurred pointed to someone from the ruling house. When two ancient icons disappeared from the house church of the Marble Palace, Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich was seriously suspected of the thefts. These icons were soon found with the moneylender Ergolts, who paid 980,000 rubles for them, but it was impossible to establish who had sold them — the moneylender swore he had seen the seller for the first time and did not remember his appearance. The theft on April 7, 1874, of three diamonds from the setting of the icon of the Vladimir Mother of God ended the investigation — no one doubted Nikola’s guilt anymore. These diamonds were soon found in one of the pawnshops in St. Petersburg, and they were handed in by the adjutant of Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich, Captain Varnakhovsky.

This icon was a wedding gift to Konstantin Nikolaevich and Alexandra Iosifovna from Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. The Grand Duchess could not calmly endure this incident and fell ill with a nervous disorder. It was not in the interest of the imperial family for society to learn about this story, so further investigation was entrusted to the Third Department. During interrogation, Varnakhovsky testified that he received the diamonds from Fanny Lear, who gave them to him on behalf of his commander. Interrogations of Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich began, conducted by the chief of the gendarme corps, Count Shuvalov, in the presence of his father. Count Shuvalov personally went to the Marble Palace to inform the parents that their son was a thief. At first, Nikolai denied the accusations against him but eventually confessed to the deed.

The guilt of the prince or his adjutant was never proven, although the investigation leaned toward the idea that Nikolai Konstantinovich was behind the crime. Opinions differ — some researchers believe that Nikolai Konstantinovich consciously took the blame to save a close person from inevitable execution. Others think the theft was committed on his orders. Still others believe the scandal was fabricated to remove yet another potential heir from claims, with the possibility of appropriating part of his inheritance. The truth will most likely remain hidden under the veil of time.

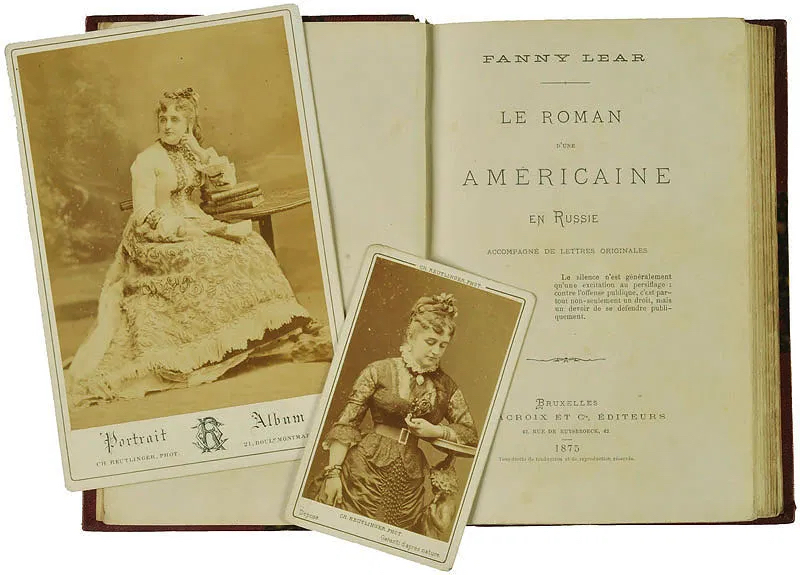

There was one "aggravating" circumstance in the prince’s history — his love for women. His origin, charisma, wit, and boundless generosity, combined with the status of "the first beauty of the dynasty," ensured him constant success in conquering hearts. In his youth, the prince never missed balls, and at one of them, he met a dancer of American origin under the pseudonym Fanny Lear (real name Harriet Blackford). She was divorced and had a daughter from that marriage. At first, no one paid much attention to this romance, but soon it became noticeable at court that it was not just a fleeting affair. The seemingly innocent romance gradually gained momentum. Fanny completely captivated the prince, which did not escape the notice of his relatives. Such a woman with free morals was not suitable as a companion for a member of the royal family, and her presence had to be eliminated.

She became the main motive for the crime — according to the family’s version, the endlessly in love prince decided to commit theft to please his beloved with luxurious gifts.

Fanny Lear was expelled from the empire with a lifetime ban on returning. An interesting fresh, ironic view of the imperial family from the frivolous Fanny.

It is not surprising that her "American Woman’s Romance in Russia" instantly spread across Europe and was discussed in all salons. Probably, the effect of this book was even more shocking than the infamous TV interview of Meghan Markle and Prince Harry. After all, nowadays no one is surprised by social gossip, but in the 19th century, society was much more conservative.

The prince failed to obtain either justification or forgiveness. By decision of the family council, he was disowned, deprived of property, titles, and the legal right to start his own family. To avoid publicity, he was declared mentally ill and sent into exile in Crimea, and then to Orenburg. In the Southern Urals, the prince committed another "unheard-of audacity" — despite the ban on marriage, he secretly married the daughter of the local police chief, Nadezhda Alexandrovna Dreyer, and soon they had a son. Almost 10 years later, after the assassination of Emperor Alexander II, his wanderings on the outskirts of the Russian Empire ended — permission was granted to return to beloved Turkestan and take his family with him, who never received official status or recognition. Thus, Prince Romanov ended up in Tashkent, where he lived for almost forty years until his death.

In any case, the imperial family decided to expel Nikolai Konstantinovich from the capital. To the public, the prince was declared insane, and he was stripped of all awards and property. Over several years, the young man changed several cities until he finally ended up in Tashkent. It should be noted that the disgraced prince built schools, hospitals, mosques, and cinemas here at his own expense.

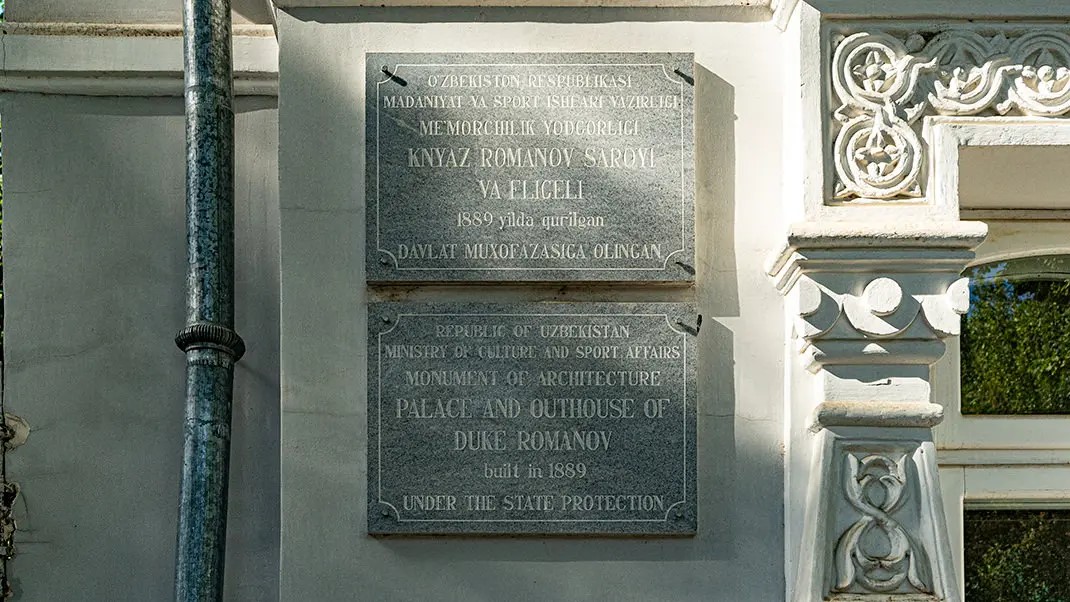

The palace in Tashkent was built in 1891 according to the design of architects Wilhelm Solomonovich Heintzelman and Alexei Leontyevich Benois for Prince Nikolai Konstantinovich, exiled to the empire’s outskirts — the Turkestan region. The left wing of the palace housed the Grand Duke’s apartments, and the right wing housed his wife’s apartments.

The palace was a long, two-story building made of fired gray-yellow bricks, with specially equipped basement rooms for living, where it was cool even in the heat. The basement also housed a large kitchen. Round towers were built on the flanks of the palace, beautifully blending with the building.

On the territory around the palace, a garden was laid out by the famous Tashkent botanist and pharmacist I. I. Krause. A circular, wide driveway alley in the form of a covered glazed portico with columns led from the street to the porch facing Kaufman Avenue. From the street, this area was fenced off by a beautiful, tall wrought-iron grille with two gates: entrance and exit. Between the grille and the driveway alley was a round flower bed fenced with trimmed plants in the form of a hedge. On both sides of the entrance staircase, on marble pedestals, lay life-sized bronze deer with huge branched antlers.

Entering through the wide oak carved double doors located at the front of the palace, the visitor entered a large round hall finished with dark wood, with an intricately shaped lantern hanging on an iron chain. From the hall, three doors opened: straight ahead, and to the right and left. Behind the left door was a round spiral patterned iron staircase leading to the second floor — to a rich, large library and billiard room. Entering the right door, the visitor found themselves in a spacious winter garden. Here grew palms of various kinds, as well as lemon, orange, mandarin, and bitter orange trees.

To the left of the entrance to the winter garden was a Japanese garden with dwarf fruit trees; in this garden, streams murmured, over which beautiful bridges with railings in the form of fences and tunnels were thrown, and there were tiny houses and many figurines of people and animals in picturesque poses. There were also gazebos made of flowering tropical plants in the garden.

Passing through the left door from the hall, the visitor entered three halls designated for the collection of paintings and marble statues, following one after another. The treasury of art objects moved to the residence in 1891 and, at Romanov’s initiative, became a center of art and the first art gallery in Central Asia, accessible not only to the aristocratic class but also to ordinary residents. Visiting the residence was an extremely exciting event for townspeople, for which they prepared carefully and dressed up. Tours for guests were also conducted by the prince himself, who enthusiastically told stories about the paintings themselves and the history of their appearance in the collection.

The door opposite the entrance led from the hall to other rooms of various sizes. In the first small sitting room near a huge French window stood

a charming statue of Venus, which looked pink-translucent when illuminated by sunlight streaming through the window. In the next hall, in glass cabinets and showcases, were numerous exhibits from Nikolai Konstantinovich’s collection — figurines, ivory toys, orders, medals, rings, bracelets, silver and gold jewelry, and many other interesting items of this kind.

The next hall was decorated in an oriental style with wonderful Bukhara, Afghan, Turkmen, and Persian carpets, with precious weapons — firearms and cold steel. Low divans were covered with carpets and fabrics embroidered with silk, silver, and gold. This hall also housed paintings by famous masters depicting scenes from Asian life.

From the "Venus" hall, a door led to a small hall where everything related to the Khivan campaign of 1873 was gathered: paintings, books, cast-iron figurines, both individual and group. As written in his memoirs by Nikolai Konstantinovich’s son — Prince Alexander Iskander — there was a model of the Khivan fortress Ichan-Kala, which Turkestan riflemen stormed wearing kepis with neck flaps: "they climbed ladders, falling wounded and killed. The Khivans, defending the fortress, shot at the besiegers with rifles and bows, threw stones and poured hot resin. Copper cannons fired both below and on the fortress. Here a Cossack carries a wounded comrade. A Cossack carries a Khivan woman. A Cossack, galloping, lifts his cap. And here lies a wounded Cossack, and near him his faithful horse sniffs him, does not leave! There is a falcon and golden eagle hunt depicted there."

Among the rooms on the first floor was a dining room entirely paneled with wood; the ceiling along the cornices was painted with gold, ink, crimson, and green inscriptions — prayers from the Quran. A large, long dining table, massive chairs with high backs upholstered in leather, with rich carved legs, backs, and armrests. Along the walls were cabinets with massive family silverware; dishes, crystal, and sets ordered from the Imperial Porcelain Factory.

In one of the wings, the Russian prince arranged a menagerie, which housed wild animals native to the region at that time. On Sundays, the menagerie was open to the public.

In fact, funds were allocated for the palace, with which, besides the palace, he built a theater in Tashkent.

His wife later secretly came to him.

Nikolai Konstantinovich was extremely popular among the local population. He opened the city’s first cinema, a bakery, built a princely soldiers’ settlement in the city center,

and constructed irrigation canals in the Hungry Steppe.

Under Soviet rule, a museum was organized in the palace, as Nikolai Konstantinovich, before his death in 1918, donated the palace to the city of Tashkent on the condition that a museum be established there. The prince himself died in January 1918 from a rapidly progressing pneumonia.

The collection of European and Russian paintings gathered by the Grand Duke and brought from St. Petersburg became the basis for the creation in 1919 of the Museum of Arts in Tashkent, which has one of the richest collections of European paintings among art museums in Central Asia.

Later, from the 1940s to the 1970s, due to the relocation of the Museum of Arts to a new building, the palace housed the Republican Palace of Pioneers, the Museum of Antiquities and Jewelry Art of Uzbekistan (until the early 1990s). At the end of the 20th century, the building was restored and today functions as the Reception House of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Uzbekistan, continuing to be a symbol of the city’s rich cultural life.

But that’s not all — in January 2019, a treasure worth more than $1 million was found in the basement of this palace: coins, icons, paintings, dishes, etc. There are talks about whether the heirs should receive anything, but nothing is known about the great-grandchildren, and for now, the treasure is being handled by the museum and specialists.

Sources:

https://4traveler.me/travel/tashkent/dvorec-knyazya-romanova-v-tashkente

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Дворец_Николая_Константиновича

https://dzen.ru/a/Ybuq813rSyA1aNJK

https://annapeicheva.ru/fannylear/

https://oadam.livejournal.com/289677.html