86QQ+3X8, Qorasaroy Street, Tashkent, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

The sacred book, the Quran, was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by Allah (God) Himself through the archangel Jibril (Gabriel). Over 23 years, the Quran was conveyed to the Prophet Muhammad in parts. During the Prophet’s lifetime, there was no need for a written text of the Quran, as oral explanations on any matter could always be obtained directly from the Prophet. However, during the times of the caliphs, disagreements began to arise, so by order of the third caliph Uthman (Uthman ibn Affan al-Umayyad al-Qurashi) in 650, Zayd ibn Thabit (the Prophet’s former personal secretary) began collecting all the Prophet’s records to unify them into one book. Simultaneously, four other assistants collected records and interviewed people, after which they compiled four versions of the text. Then all texts were compared and consolidated into one, which was recorded, and all other variants and drafts were burned to avoid disputes.

The oldest surviving manuscripts with Quranic texts date back to the late 7th or early 8th century, i.e., to the time of the edition carried out by order of al-Hajjaj. Among them is the so-called Uthmanic (more precisely, Zayd-Uthmanic) codex of the Quran, which for centuries was presented by theologians as the original from which copies were supposedly made. However, the Uthmanic codex already has diacritical marks (lines replacing the usual dots in Kufic script), but it still lacks other superscript and subscript signs adopted in later Arabic script (hamza, madda, tashdid, sukun, short vowels).

This copy of the Quran is traditionally considered one of six commissioned by the third caliph Uthman (Uthman). In 651, nineteen years after Muhammad’s death, Uthman entrusted a specially selected commission to prepare a standard copy of the Quranic text. Five of the six authoritative manuscripts were sent to major Muslim cities of that era. The sixth copy was kept by Uthman for personal use in the caliphate’s capital, Medina. However, modern research casts doubt on the Samarkand Quran’s belonging to the first edition. It was previously believed that the only surviving copy was in the Topkapi Palace in Turkey, but more thorough analysis showed that the Topkapi manuscript was written significantly later than the 7th century.

In 656, rebels, supporters of his successor, Caliph Ali, stormed Caliph Uthman’s palace disguised as pilgrims and killed him with swords. According to legend, at the moment of his death, Caliph Uthman was still reading the Quran, the pages of which were stained with his blood. From that moment, Uthman’s Quran became a sacred relic.

Ali, who succeeded Uthman as caliph, moved Uthman’s Quran to Kufa in Iraq. The subsequent history of this manuscript is known only from legends. In the 15th century, Uthman’s Quran appeared in Samarkand. According to legend, the relic was brought by Timur from his campaign in Basra (present-day Iraq). Another legend says that the Quran was delivered from the Sultanate of Konya to Samarkand by the Sufi guru Khoja Akhrar, who received it as a gift for healing the caliph.

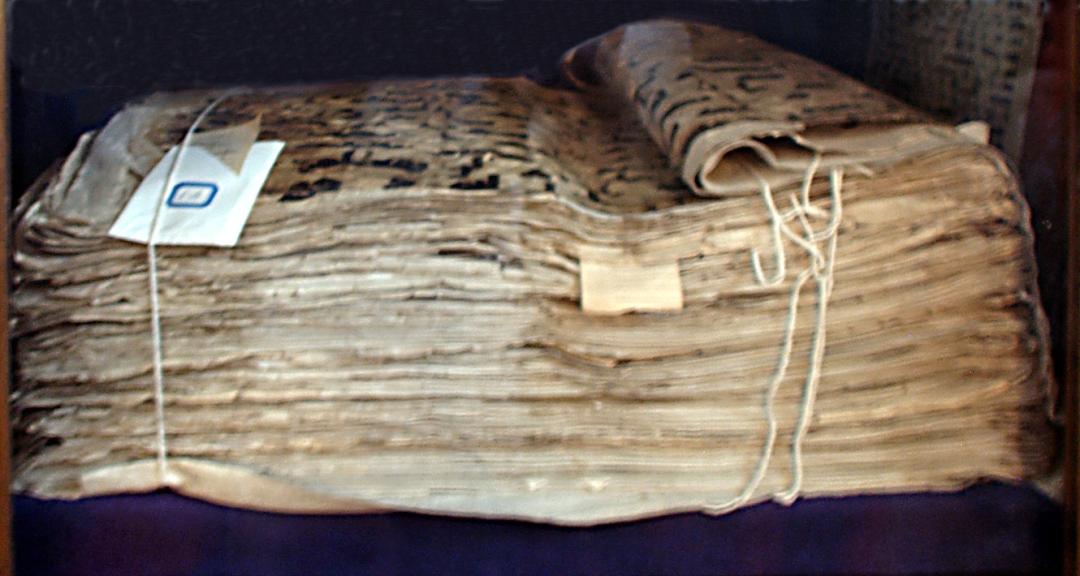

Impartial research of the codex showed that it could not have been written earlier than the end of the first quarter of the 8th century, or in other words, the beginning of the 2nd century of the Hijra, i.e., half a century after Caliph Uthman’s death. Regarding the “holy blood of Caliph Uthman,” supposedly staining this codex, the Arabist A.F. Shebunin (1867–1937), who studied it, wrote: “Perhaps long ago there was less blood than now; perhaps the bloodstains underwent the same restoration as... the text did — now we cannot say this for certain, but one thing is undeniable: whether long ago or recently, the stains we see now are applied not accidentally but deliberately, and the deception is so crude that it betrays itself. The blood is on almost all the spines and spreads more or less far onto the middle of the page. But it spreads symmetrically on each adjacent page: obviously, they were folded when the blood was still fresh. And there is also the strangeness that such stains do not cover all neighboring pages continuously but every other page... Obviously, such distribution of blood could not have happened by chance, and we find it consistently.” Blood traces are present on all three oldest Quranic copies traditionally associated with Uthman. Thus, impartial paleographic research showed that this codex, long held by the Muslim clergy of the Khoja Akhrar mosque in Samarkand, is not identical to the one it was claimed to be. At the same time, credit must be given to those who worked on this huge ancient manuscript, copying and decorating it. It is executed on 353 sheets of thick, sturdy parchment, smooth and glossy on one side, yellowish in color, and white with fine wrinkles on the other. Each sheet has 12 lines, with the text occupying a significant area — 50 by 44 centimeters, and the overall sheet size is 68 by 53 centimeters. In place of 69 missing, torn, or lost sheets are paper sheets imitating parchment. Each Quranic verse is separated from the next by four or seven small lines, and the verses are grouped, marked by a colored square with a star, in the center of which is a circle with a red Kufic letter whose numerical value indicates the number of verses from the beginning of the surah. Each surah is separated from the next by a colored band of patterned squares or painted elongated rectangles. The surahs have no titles but all, except the ninth, begin with the traditional “Bismillah” — the words “In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.”

The manuscript’s dating is based on orthographic and paleographic studies. Radiocarbon dating showed a 95.4% probability that it was written between 765 and 855 CE. However, one fragment of another manuscript (kept in the Museum of the Muslim Administration of Uzbekistan in Tashkent) was dated between 595 and 855 CE with 95% probability.

The Quran remained in the Khoja Akhrar mosque in Samarkand for four centuries until 1869, when Russian General Abramov bought it from local mullahs and later handed it over to the Turkestan Governor-General Konstantin von Kaufman, who in turn sent it to the Imperial Library of Saint Petersburg (now the Russian National Library). The manuscript’s appearance attracted the attention of Orientalists, and eventually a facsimile edition was published in Saint Petersburg in 1905. The 50 copies issued soon became rarities. The first detailed description and dating of the manuscript were undertaken by the Russian Orientalist Shebunin in 1891.

Notably, there is a letter from V.I. Lenin to the People’s Commissar for Education A.V. Lunacharsky dated December 9, 1917, about this rare manuscript. “The Council of People’s Commissars,” the document states, “received a request from the Regional Muslim Congress of the Petrograd National District, which, in fulfillment of the aspirations of all Russian Muslims, asks to hand over to the Muslims the ‘Sacred Quran of Uthman,’ currently held in the State Public Library.” “The Council of People’s Commissars,” the letter concludes, “has decided to immediately hand over the ‘Sacred Quran of Uthman,’ held in the State Public Library, to the Regional Muslim Congress, and therefore asks you to make the appropriate arrangements.” Based on this letter, the “Quran of Uthman” was immediately handed over to representatives of the Regional Muslim Congress of the Petrograd National District and then delivered to Ufa. In June 1923, a congress of Muslim clergy was held in Ufa, where one of the topics was the issue “on the transfer of the Sacred Quran of Uthman to the Turkestan Muslims at the request of the Turkestan Republic.” A commission was formed, including the mufti and members of the Spiritual Administrations from Tashkent, Astrakhan, and Moscow. Riza Fakhretdinov was appointed chairman of the commission. Orientalist Alexander Schmidt also participated in the delivery. In August 1923, the Quran of Uthman was transported in a special carriage to Tashkent, where its transfer was formalized. The commission members visited several cities of the Turkestan Republic, meeting with local ulema. After returning to Ufa, Fakhretdinov wrote an essay “On the Journey to Samarkand for the Return of the Quran of Uthman” (lost).

Then the Quran of Uthman was handed over to Samarkand, where it was kept in the Khoja Akhrar mosque. Since 1941, its place of storage has been the Museum of the History of the Peoples of Uzbekistan in Tashkent.

On March 14–15, 1989, the 4th Kurultai of Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM) was held in Tashkent, where, by decision of the government of the Uzbek SSR, the Quran was withdrawn from the museum and solemnly handed over to representatives of the faithful. After Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991, SADUM was renamed the Administration of Muslims of Uzbekistan, which is under the Committee for Religious Affairs of the Cabinet of Ministers. In the early 1990s, the relic was handed over to the mufti by Islam Karimov on Hast Imam Square. The Quran was placed in the building of the Administration’s library, located in the Barak-Khan madrasa.

In 1997, UNESCO included Uthman’s Quran in the “Memory of the World” register. In Tashkent, in the Muyi Mubarak madrasa, part of the Hazrati Imam Ensemble, the only surviving original Quran manuscript is kept, as certified by a certificate issued by the International UNESCO Organization on August 28, 2000.

The manuscript kept in Tashkent is incomplete. It begins in the middle of the 7th verse of the surah “Al-Baqarah” and ends at the tenth verse of the surah “Az-Zukhruf.” The manuscript has from eight to twelve lines per page and lacks vocalization.

A fragment of the Samarkand Quran containing part of the text from the surah “Al-Anbiya” is held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Sources:

https://wikiquran.info/index.php?title=Samarkand_Quran

http://www.raruss.ru/treasure/1369-samarkand-koran.html

https://adrastravel.com/ru/uzbekistan/tashkent/koran-osmana/