599F+FW Peschanoe, Leningrad Oblast, Russia

Fort Ino (Nikolaevsky) (Swedish: Ino fästning) is one of the main fortification structures that protected Saint Petersburg from the sea and land (as part of the Kronstadt position of the Naval Fortress of Emperor Peter the Great). It was built between 1909 and 1916 to defend against a possible attack by the fleet of the German Empire. It was destroyed in 1921 in accordance with the Treaty of Tartu. It was located on the Inoniemi Peninsula (northern coast of the Gulf of Finland), near the village of Ino (now the settlement of Privetninskoye).

In 1909, the General Staff approved a plan to create an advanced mine-artillery position 60 km west of Saint Petersburg at the narrowing of the Gulf of Finland — the Stirsudden Strait. Its core consisted of two new coastal forts, each capable of successfully engaging in artillery duels with a battleship fleet and preventing mine sweeping. On the southern shore of the gulf, construction began on Fort Alekseevsky on a coastal elevation near the village of Krasnaya Gorka; on the northern shore, on the cape near the settlement of Ino (Privetninskoye), Fort Nikolaevsky was built. Their advanced batteries on Cape Gray Horse on the southern shore and near the settlement of Pumala (Peski) on the northern shore were positioned 6 km further west.

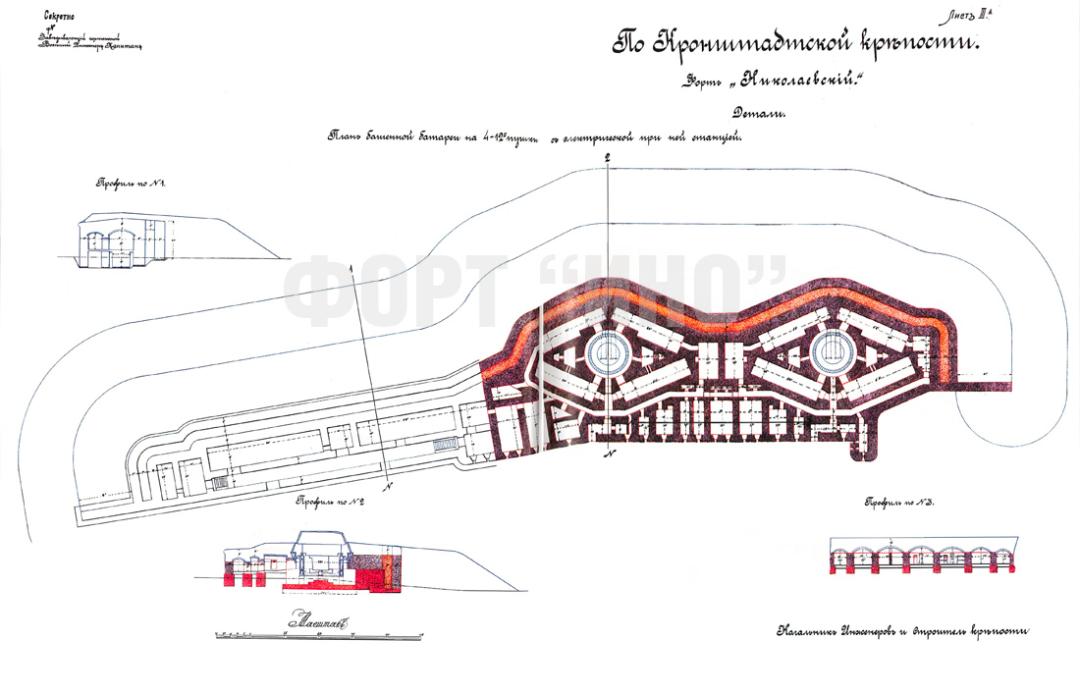

Forts "Nikolaevsky" and "Alekseevsky" were designed taking into account the most modern achievements of Russian engineering thought and bore several key features of the so-called "Russian fort" by the outstanding fortification engineer K. I. Velichko. A significant distinction of the Fort Ino project from the classic Velichko fort was the presence of large-caliber artillery (in fact, this was the very purpose of its construction). Moreover, 305-millimeter caliber guns were used for the first time in coastal fortifications.

The village of Ino was the largest village in the Uusikirkko volost of the Vyborg Governorate of the Grand Duchy of Finland. A typical Finnish village consisted of dozens of farmsteads scattered over a large area. In addition, dachas were built here (before the revolution, there were 68 dachas and villas owned by Petersburg residents; the most famous dacha owners included academician V. M. Bekhterev and artist V. A. Serov). Only Milyukov and Maté voluntarily transferred their dachas to the treasury at the start of the fort's construction. Valentin Serov's land plot was not listed within the fort's territory, and his dacha was demolished during the construction of the railway to the fort. The land acquisition cost the treasury 418,379 rubles. The dachas were used to house the fort's garrison.

At various times from 1909 to 1918, the work on the fort was carried out by military engineers Lieutenant Colonel Smirnov, Captain Lobanov, Captain Poplavsky, Captain (later Lieutenant Colonel) Budkevich, Lieutenant Colonel Krasovsky, and engineer Rosenthal.

The fort had two coastal batteries with four 152-millimeter Canet guns (on the flanks), a battery with eight 254-millimeter guns, and a battery with eight 279-millimeter howitzers, which fired at ranges of 15-18 kilometers. Around the guns was an entire underground complex covered with a two-meter layer of concrete, designed to withstand hits from large-caliber naval artillery shells. There were ammunition depots, barracks, a railway for delivering shells to the guns, command and observation posts. The positions were protected by a 3-meter concrete parapet. The fort was surrounded by a rifle rampart with concrete strongpoints and was adapted for all-around defense.

In 1912, construction began on two four-gun batteries of 305-millimeter guns at the fort — a turret battery and an open battery. The turret battery was a concrete structure with two twin-gun turrets designed by A. G. Dukelsky and was the latest technical achievement of that time. Inside were casemates, gun magazines, barracks, an underground railway on which shells were transported by carts, and an electric elevator. Steam-water heating was installed. By 1916, both batteries were combat-ready. Around them were concreted trenches with shelters for guns and infantry, connected to the turret battery by underground passages.

According to the project, the minimum garrison was set at 2 companies of fortress artillery and 2 companies of infantry, but if necessary, the fort could accommodate up to 2 battalions of artillerymen and 1 battalion of infantry. By the start of World War I, the garrison was staffed according to wartime tables. There were 2,000 artillerymen, the same number of infantry, more than 500 other servicemen (miners, sappers, Cossacks, etc.), and militia. By January 1917, the garrison numbered 5,500 people.

In 1915, despite not all construction work being completed, the fort was put on combat duty. By 1917, its trained and cohesive garrison consisted of nearly five thousand people. By January 1, 1917, all the fort's artillery batteries were completed and combat-ready.

In December 1917, the Grand Duchy of Finland gained independence. The border between the new states ran along the old administrative boundary of the Grand Duchy, leaving Pechenga with Russia, as it had been conditionally transferred to the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1864. To resolve the issue of this territory and officially demarcate the border, a Special Commission was created. However, only its Finnish part was formed — the Russian part was not formed due to the civil war that began in Finland at the end of January 1918.

The revolution began in Helsinki under the leadership of the Social Democratic Party and the Trade Union Organization. The revolutionary government — the Council of People's Commissars — headed by Kullervo Manner, immediately established friendly relations with Soviet Russia. At the proposal of the Council, a mixed commission was created to prepare a draft Soviet-Finnish treaty. On March 1, in Petrograd, the treaty "On Friendship and Brotherhood" between the RSFSR and the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (named so in the treaty text at Lenin's suggestion) was signed. The treaty provided for mutual transfer of territories — Fort Ino was to be transferred to Soviet Russia in exchange for the Petsamo (Pechenga) area with a year-round ice-free port in the north.

However, the revolution in Finland was defeated, and the parties had to start over.

But the revolution erupted, mixing not only concepts of good and evil but also state borders. In the spring of 1918, the newly independent Finland claimed rights to Ino with all its property. Encouraged by the Germans, the Finns moved troops to it, though few — about 2,000 men.

The commandant of the Kronstadt fortress, Artamonov, reported to the Military Commander of the Defense of Petrograd, Schwarz, on April 24, 1918, that the entire fortress had only 150 combat-ready defenders.

In January-February 1918, when the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army was just beginning to form, a detachment of Red Guards from Sestroretsk guarded Fort Ino in Finland. The old army was demobilizing chaotically, leaving the fort to fate. The detachment from Sestroretsk found the fort almost empty. Only a small group of revolutionary sailors delayed the disorderly flight of demoralized soldiers.

On April 24, Finnish troops besieged Fort Ino. Pursuing the Finnish Red Guard retreating to the Soviet borders, the White Finns and Germans surrounded it and proposed to start negotiations for immediate surrender. But the besieged, well-armed with a large amount of ammunition and food, refused to surrender without orders from the Soviet government.

In April, equipment and ammunition began to be removed from the fort. On April 24, 1918, during preparations for surrender, the locks on the guns were removed and taken to Kronstadt, and the batteries were prepared for demolition. Moscow feared that defending the fort could lead to the breach of the Brest Peace.

Trotsky ordered to blow up the Ino fortifications and withdraw. The text of Trotsky's telegram literally reads: "Order the garrison of Ino to blow up the fortifications. Assist them with the ship 'Respublika.' Take the Ino garrison on board. If possible, avoid naval battle and return to Kronstadt. Trotsky."

The literal quote is important for this reason. Later, Trotsky stated quite differently: "Upon receiving from Shchastny, after some time, a report from Kronstadt about the danger threatening Fort Ino from an allegedly suddenly appeared German fleet, I replied, according to the general directive, that if the situation became hopeless, the fort should be blown up. What did Shchastny do? He conveyed this conditional directive as my direct order to blow up the fort, although there was no need for demolition. The Ino fort incident became one of the charges in the case against the naval commander of the Baltic Fleet, Shchastny. Comparing the quotes, we see that at the trial the 'left of the revolution' omitted his own order to blow up the fort. Shchastny ignored this order. However, it was necessary to decide what to do with the fort now. The Finns appealed to the Brest Peace terms and demanded the fortress's surrender. The fort did not surrender, and skirmishes began on the approaches. Fresh units arrived to the defenders, but on May 13 a new telegram from Trotsky arrived:

It is forbidden to support Fort Ino with garrisons or ships of the Baltic Fleet. The fort must be held by its own forces. If it is impossible to hold due to the actual pressure from the enemy, the fort must be blown up with all artillery."

On May 5, 1918, Germany demanded the fort be handed over to Finland.

The detachment held the defense until an icebreaker and a warship from Kronstadt broke through with a government commission proposing to blow up the fort to prevent leaving a heavily fortified military base to the enemy.

In the second half of May, the last days of Fort Ino came. When the detachment left its shores, bright tongues of flame devoured wooden buildings, kitchens, and barracks. Being far from the shore, the Red Army soldiers heard several powerful explosions. The fort's fortifications did not fall into enemy hands.

Ultimately, the decision to blow up Ino was made by the commandant of the Kronstadt fortress, Artamonov, who explained his actions as follows: "On May 14 at 23:30, Fort Ino was blown up by my personal order. I came to the decision to blow up the fort based on the following considerations: operational, political, and civil. On April 24, the fort was surrounded by Finnish troops, whose advanced posts were located about 250 steps from the turret battery on one side and 100 steps from the harbor on the other."

In response to the Finnish detachment commander's demand to surrender the fort, he was refused, and measures were taken to create the fort's defense, for which the 6th Latvian Tukums Regiment — about 400 bayonets, the Novgorod Red Army battalion — about 400 bayonets, the Vyborg Red Army battalion — about 200 bayonets, and 125 machine gunners of the 1st Machine Gun Regiment arrived at the fort. Of these units, only the Latvian regiment was an organized military unit; the others were undisciplined, poorly trained teams not accustomed to following combat orders without question. In addition, about 250 people enlisted in the 2nd Kronstadt Artillery Division were at the fort, from whom personnel for two batteries (Canet) were organized. The 12- and 10-inch batteries were left without crews, and there was no one to take them due to the complete absence of trained personnel. Due to the inability to use these batteries, their locks were removed and taken to Kronstadt so that, in the event of a sudden capture of the fort by the White Guard, these guns could not be turned against Kronstadt. Thus, the fort's significance in terms of the ability to fight the enemy fleet was nullified. The whole issue was about buying time for the possible complete evacuation of property from the fort. Experience showed that, given the current state of the workers, labor productivity had fallen so much that removing heavy guns would take many months. The fort's garrison was busy setting up wire obstacles and digging trenches on the eastern facade of the fort, which lacked any fortifications. The fort was mined with demolition charges totaling 300 poods of pyroxylin; 24 poods of pyroxylin were laid under the turret bases. The explosion was to be used as a last resort to prevent the fort from falling into the hands of the White Guard. Due to the overall political situation, it was clear to me that if the German government issued an ultimatum to hand over the fort with all its armaments, such an ultimatum would be fulfilled, and therefore I would have to blow up the fort against orders from above, as I did not consider it possible to surrender it without demolition. Therefore, I decided to carry out the explosion without waiting for an order to surrender, thus resolving the issue of Fort Ino and sparing the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs from having to agree again to German demands."

I believed that by blowing up the fort on my own initiative, I was taking on a very serious responsibility but at the same time completely depriving the Germans of the possibility of acquiring the fort's guns by any means. I thought that endless concessions made to the German government would accustom it to the idea that there were no longer people in Russia capable of causing it real trouble, and therefore I considered it my duty as a Russian citizen to seize the opportunity to prove otherwise."

On May 14, 1918, at 23:30, the turret batteries of Fort Ino were blown up by the personnel, and the fort itself was captured by the Finns, as Artamonov K. A. wrote in his report.

Soon, however, it turned out that the three main batteries of the fort with the most powerful guns, due to a strange coincidence (still debated by historians), were only slightly damaged by the explosion. Therefore, the Finns had big plans for the fortress of the former empire that came to them so easily. But it was unlucky again. In 1921, fulfilling the terms of the Treaty of Tartu, the new owners themselves blew up the remains of the fort, showing their trademark thoroughness in this matter and having previously removed absolutely everything even remotely useful. This is not just about metal beams from the casemate ceilings or guns (one of the armored turrets of Ino with two 305-millimeter "monsters," installed on the island of Kuivasaari, still functions properly and conducts blank firing once a year for public entertainment). The trophies also include 17,000 metal stakes for barbed wire and almost two kilometers of armored shields for infantry, which were later installed on the infamous Mannerheim Line.

"But the most important thing is not even this," notes military historian Alexander Ivanovich Senotrusov, "four of the engineers who built Ino, far from the least important, went to the Finns. That is, invaluable fortification construction experience also went there."

The fort's guns were later used in Finland's coastal defense system — for example, 305/52-millimeter guns were installed in an armored turret (from the unfinished 14" battery of Myakiluoto) on Kuivasaari Island.

The much-suffering fort changed ownership several more times. After the Winter War, it became Soviet. In 1941, the Finns returned there again and fired on Kronstadt from captured Red Army guns brought from the front, and from the surviving "imperial" observation post, they monitored Peterhof, Lomonosov, and even Leningrad. By the way, some experts believe that if the fort had remained in our hands in 1918, the northern boundary of the city's blockade would have been pushed back by at least 30 kilometers. After the war ended, Ino again became part of the USSR.

During Soviet times, a 152-millimeter battery was built on the fort's territory, but it was decommissioned in the early 1960s.

In the 1950s, the military settled there again. The cape was divided among the Air Defense Forces, the Engineering and Technical University, and a special laboratory studying the effects of radiation on living organisms. Yes, it really was there, but this does not mean, as rumors say, that the entire Ino area was a testing ground for it, resulting in alleged sightings of mutant dogs in the settlement.

This part was, of course, strictly classified, and even today little reliable information is known about its activities.

Until the mid-1980s, the territory was under a closed regime. Entry was only by passes. This was due to the presence of military units, a border outpost in the fort area, and mainly because a highly secret testing ground existed in the postwar years in the former Fort Ino area. According to locals who serviced this underground complex, experiments were conducted there to study the effects of intense radiation on animals. The testing ground was later liquidated, but access to the fort remained closed. Until the end of the 20th century, Fort Ino was occupied by a military unit and the Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense of Russia.

One thing is clear: after the general devastation of the turbulent 1990s, when the military left the fort, what remained was a guarded "patch" about one square kilometer in size, where a properly equipped storage facility for spent materials is located.

"All rumors about creeping radiation from the fort have been spread for many years by 'special' people and media pursuing their own goals," shares St. Petersburg fort expert Alim "Technogen." "The background radiation there is fine. Outside this zone, there are no spots except for the place where the lighthouse once stood. Looters dismantled it for metal, and the lamp with a radioisotope power source was thrown on the shore. There, if desired, one can find a slight increase in radiation levels."

This is also confirmed by longtime fort researcher and local resident Yuri Khomyzhenko: "The maximum I measured at Ino is the same as on the embankments in St. Petersburg. And in the forest near the burial ground, there is even less."

Looters still operate in the ruins, trying to find fragments of armor and metal structures under concrete debris, which can rightfully be considered unique artifacts. In 2017, part of the fort's territory was recognized as a cultural heritage site included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. However, "metal hunters" apparently do not know this, as there is no corresponding information or security at Ino.

Several years ago, the area under the jurisdiction of military engineers on the cape came to life again. Cadets even began clearing soil and debris from a relatively well-preserved part of one of the gun batteries, allowing a clearer picture of how this unlucky fort looked in its brief period of power.

Everything is overgrown with forest. Metal has been dismantled where possible. The huge ditches of strongpoints No. 1 and 2 are well preserved; at strongpoints No. 7 and 8, the glacis-shaped profile of the positions is clearly visible. The staircase of the former Kurapatkin dacha, converted during World War I into a temporary hospital, remains. The staircase leads to the bay. Clean sand, huge boulders, and on the horizon a chain of tanker accumulators serving as floating oil transfer bases. In 2020, the Military Engineering Institute of the Academy of Material and Technical Support of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation developed a project to revive Fort Ino.

Sources:

https://spbdnevnik.ru/news/2020-02-10/fort-ino-mesto-nevezeniya-ili-102-goda-zhizni-posle-smerti

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ино_%28форт%29#Уничтожение

https://sputnikipogrom.com/history/72686/the-other-civil-war-2/