This building is located in the city center. Unlike many others, it has no memorial plaque. And few remember that here, in the apartment of the Putyatin princes, on March 3, 1917, the more than 300-year history of imperial Russia came to an end. Textbooks mention this event, which drastically changed the country's life, in just two or three lines: they say that after consulting with members of the Provisional Government, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich signed the Manifesto of Abdication. But how exactly did it happen?

At the meeting, besides the Grand Duke, there were seven ministers of the Provisional Government and five deputies of the State Duma led by Rodzianko. Some of them left memoirs, thanks to which we can reconstruct the long-past events. But first—a few words about who was destined at that moment to take responsibility for the country.

It is commonly believed that the last Russian emperor was Nicholas II. But after his abdication, there was another—Michael Romanov. Only he reigned less than a day, from March 2 to 3, 1917. Abdicating the throne in favor of his younger brother, the former autocrat sent him a telegram: “To His Imperial Majesty Michael II. The events of recent days have forced me to irrevocably take this extreme step. Forgive me if I have upset you and for not warning you in time… I fervently pray to God to help you and our Motherland. Nicky” (this text was first published 65 years later in issue 149 of the “New Journal”). Thus, the prophecy came true: the Romanov dynasty began with Michael I and ended with Michael II.

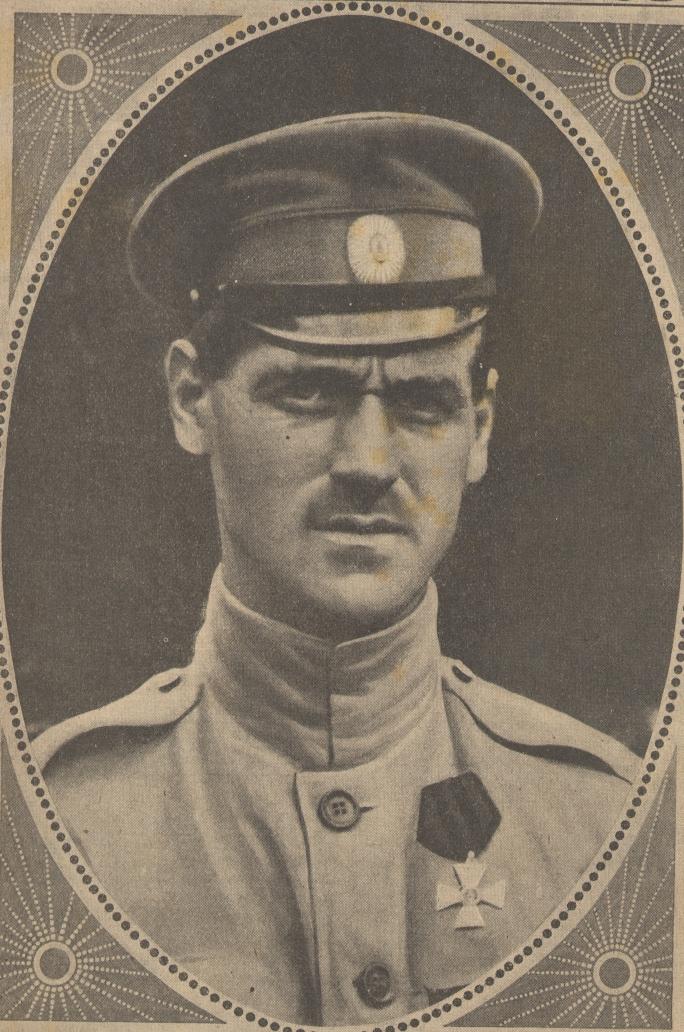

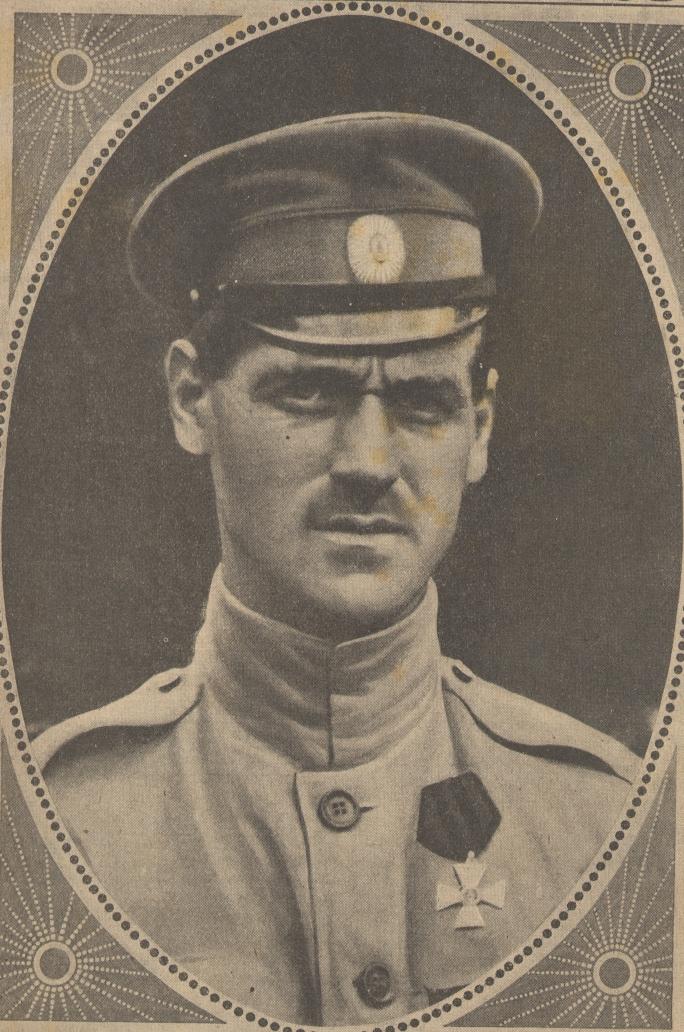

The Grand Duke—the youngest son of Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna—was born on November 22 (December 5), 1878, in Saint Petersburg. He spent his entire life in the shadow of his elder brother. He was very modest, but that did not prevent him from becoming a brilliant officer and, during World War I, a combat general. It is no coincidence that the horsemen serving under Michael in the Caucasian Native Cavalry Division (the Wild Division) called him “Dzhigit Misha,” “the bravest of the brave.”

Shortly before the monarchy’s collapse, the leaders of the “Progressive Bloc” invited the Grand Duke to one of their meetings and asked: was Michael Alexandrovich ready to succeed the throne? He replied:

— May this cup pass me by…

And so, the burden of supreme power fell on this man’s shoulders, beyond his will.

Early on March 3, after receiving the telegram about Nicholas II’s abdication, a meeting was held of members of the Provisional Government and the Provisional Committee of the State Duma. Milyukov, Guchkov, and Shulgin spoke in favor of the monarchy, arguing that Michael had no right to refuse the throne. Rodzianko and Kerensky thought otherwise. But Michael had already become emperor, and the news was sent throughout the country. The army was about to swear allegiance to him. Those gathered in the Tauride Palace understood: it was necessary to urgently meet with Michael Alexandrovich.

Learning that members of the Council of Ministers would soon arrive at 12 Millionnaya Street, the Grand Duke was not surprised. Only Michael Alexandrovich believed he would be offered to become regent for his underage nephew. But events rapidly unfolded…

The room was prepared for the meeting. The deputies, mostly in favor of Michael Alexandrovich’s abdication, were anxious: what would happen if he refused? Prime Minister Prince Lvov and seven other ministers would resign. Rodzianko might also be out of a job. And with the emperor would remain the Minister of Foreign Affairs and possibly the Minister of War, Guchkov.

At quarter to ten, a tall, youthful man entered the hall and shook hands with everyone. Fear was evident on the faces of those present, skillfully fueled by Kerensky. Several times he said that armed men could burst in at any moment and kill everyone. Rodzianko and Prince Lvov echoed him. Milyukov urged the Grand Duke not to refuse the throne:

— If you refuse… it will be disaster! Because Russia will lose its axis… The monarch is the axis… The mass, the Russian mass… Around what will it gather?.. If you refuse, there will be horror! Complete uncertainty, because there will be no oath!.. There will be no state! No Russia! There will be nothing…

Kerensky interrupted him:

— …By accepting the throne, you will not save Russia! On the contrary… I know the mood of the masses… Right now, sharp discontent is directed precisely against the monarchy… In the face of an external enemy, civil, internal strife will begin!.. I beg you, for Russia’s sake, to make this sacrifice!..

Silence fell in the living room. Then Guchkov made a final effort. As French diplomat Maurice Paleologue writes, “addressing the Grand Duke personally… he began to prove to him the necessity of immediately presenting the Russian people with a living image of a popular leader:

— If you are afraid, Your Highness, to immediately take upon yourself the burden of the Imperial crown, accept… supreme power as ‘Regent of the Empire until the Throne is occupied,’ or… the title of ‘People’s Protector’… At the same time, you could solemnly pledge to the people to hand over power to the Constituent Assembly as soon as the war ends.

This excellent idea… caused Kerensky to have a fit of rage, a storm of curses and threats.”

No result was reached. Michael Alexandrovich said he wanted to discuss the situation privately with two of those present before making a decision. He chose Prince Lvov and Rodzianko. The first was the Prime Minister, the second the Chairman of the State Duma. From them, he wanted confirmation that the Provisional Government could preserve the existing order and guarantee the conditions necessary for elections to the Constituent Assembly.

Rodzianko repeatedly asserted that transferring powers to the Constituent Assembly did not exclude the possibility of the dynasty’s return to power. He told the Grand Duke the same: abdication would not have fatal consequences for the crown. For Michael, these words were a convincing argument, and after weighing everything, he said:

— Under the current circumstances, I cannot accept the throne.

Everyone was stunned. Guchkov, as if trying to ease his conscience, shouted:

— Gentlemen, you are leading Russia to ruin; I will not follow you…

At 12 Millionnaya Street, two well-known lawyers—Baron Nolde and Nabokov—were summoned. They understood that by law, Nicholas II had no right to abdicate the throne on behalf of his son. But he did, and his will had to be fulfilled. After discussing the situation, they decided a political Manifesto was needed. Thus, the document called the Manifesto of Abdication appeared. But interestingly—the word “abdication” does not appear in the text:

“A heavy burden has been laid upon me by the will of my brother, who transferred to me the Imperial All-Russian Throne in a time of unprecedented war and popular unrest.

Inspired by the single thought shared with all the people that above all is the good of our Motherland, I have made a firm decision to accept supreme power only if such is the will of our great people, who must by national vote, through their representatives in the Constituent Assembly, establish the form of government and new fundamental laws of the Russian State.

Therefore, invoking God's blessing, I ask all citizens of the Russian State to obey the Provisional Government, arisen by the initiative of the State Duma and endowed with full authority, until the Constituent Assembly, convened as soon as possible on the basis of universal, direct, equal, and secret voting, expresses the will of the people by its decision on the form of government.

Michael.”

Michael Alexandrovich agreed to accept supreme power only if the Constituent Assembly so decided. At the same time, he empowered the Provisional Government.

From a political point of view, the Manifesto was brilliantly composed: the new emperor recognized the authority of the Provisional Government. Although he said he was not yet emperor, he could become one. Michael conditionally accepted the crown and temporarily refused it. Russia became a republic while remaining a monarchy at the same time.

From a legal standpoint, however, the Manifesto did not hold up. Grand Duke Michael could not transfer supreme power because he did not possess it himself. According to Nicholas II’s abdication, he was supposed to rule “in unity with the State Council and the State Duma.” The “abdication” canceled all three sources of power.

The Manifestos of the two royal brothers were taken to the printing house, and soon posters appeared all over the city: “Nicholas abdicated in favor of Michael. Michael abdicated in favor of the people.”

The goal of the Manifesto signed by Michael was to buy time. Members of the Provisional Government hoped, as did he, that law and order would be restored in the country and conditions created for convening the Constituent Assembly. If that happened, the Manifesto would not be a capitulation of royal power to the uprising crowd but a factor supporting the monarchy until the Constituent Assembly convened. Moreover, the idea of a “chosen” tsar by the people was not new. Michael I, from whom the Romanov dynasty began, was chosen by the Zemsky Sobor in 1613.

Immediately after the Manifesto’s publication, the gunfire in Petrograd ceased. In fact, Michael II stopped the February Revolution and gave the country, exhausted by fighting an external enemy, a respite from internal strife, delaying the start of the Civil War. When the “Red Terror” engulfed Russia, he became simply citizen Romanov—without title, military rank, positions, or financial support.

According to the generally accepted version, M. A. Romanov and his secretary were shot on the night of June 12–13, 1918, in a forest near Perm by local Chekists. But this version is based only on the memories of potential killers. They can be questioned. Paragraph 1 of Article 61 of the Civil Procedure Code of the Russian Federation states: circumstances recognized by the court as publicly known do not require proof. However, the fact of M. A. Romanov’s and N. N. Johnson’s deaths was never established by the court.

The press announced their escape. Some researchers believe that such a statement indicates the Bolsheviks’ cunning, who wanted to hide the fact of the murder. We will turn to a document written not for newspaper publication but for “internal,” party use, kept for many years in the State Archive of the Perm Region under “secret” classification. These are the memoirs of Chekist M. F. Potapov: “And Borchaninov tells me: Michael Romanov has been brought here; he must be received and guarded. For this purpose… a large room was allocated, and Michael Romanov and his secretary Johnson were placed here… They sat for three months, and I guarded them… Later it turned out… an order came to release Michael Romanov… under Cheka supervision, and he was placed in the former Royal chambers… After that… I asked to come home on leave… I was let go. And when I returned here, Michael Romanov was not here, he escaped.”

Another document giving hope that Michael Alexandrovich did not die in 1918 is the order of Baron Ungern von Sternberg, commander of the Asian Division, No. 15. It contains the lines: “The Bolsheviks have come… among the people we see disappointment… They need names… well-known, dear, and revered. There is only one such name—the lawful owner of the Russian Land, the IMPERIAL ALL-RUSSIAN EMPEROR MICHAEL ALEXANDROVICH, who saw the people’s turmoil and wisely refrained by the words of his HIGHEST Manifesto from exercising his sovereign rights until the time of the people’s awakening and recovery…”

On August 20, 1921, Baron Ungern was captured by the “Reds” and tried on September 15. He was charged with three accusations, including: he waged armed struggle against Soviet power aiming to restore the monarchy and place Michael Romanov on the throne. Baron Ungern did not deny any of the charges. On the same day, he was executed. The question arises: did he, like Perm Chekist M. F. Potapov, know that Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich survived in 1918?

It is reliably known: on the night of June 12–13, 1918, Perm Chekists kidnapped M. A. Romanov and his secretary N. N. Johnson. No one saw them again—neither alive nor dead. One hopes that someday we will learn the truth.

In 1981, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich was canonized among the New Martyrs of Russia by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. On June 8, 2009, the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation rehabilitated several members of the imperial family, including Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich and his secretary N. N. Johnson, who had been considered “enemies of the people.”

Sources:

https://adresaspb.com/category/geography/chast-goroda/millionnaya-ulitsa-dom-12/