Palace Square, 6, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 191186

The Alexander Column, erected to commemorate the victory over the French in 1812, stands in the center of Palace Square, opposite the Winter Palace. It is carved from a single piece of granite; the base of the monument is a column with a diameter of 3.5 meters at the bottom and 3.15 meters at the top (i.e., a cone), weighing 604 tons. The quarrying and preliminary processing took place from 1830 to 1832 at the Pyuterlak quarry, located in the Vyborg Governorate, in the modern village of Pyuterlakhti. After the column block was separated, stones for the monument’s foundation and a large stone for the column’s pedestal weighing over 400 tons were also carved from the same rock. They were transported to Saint Petersburg by water, using a specially designed barge.

The quarry in Finland, where the column was carved, is still operational today and supplies granite to Italy.

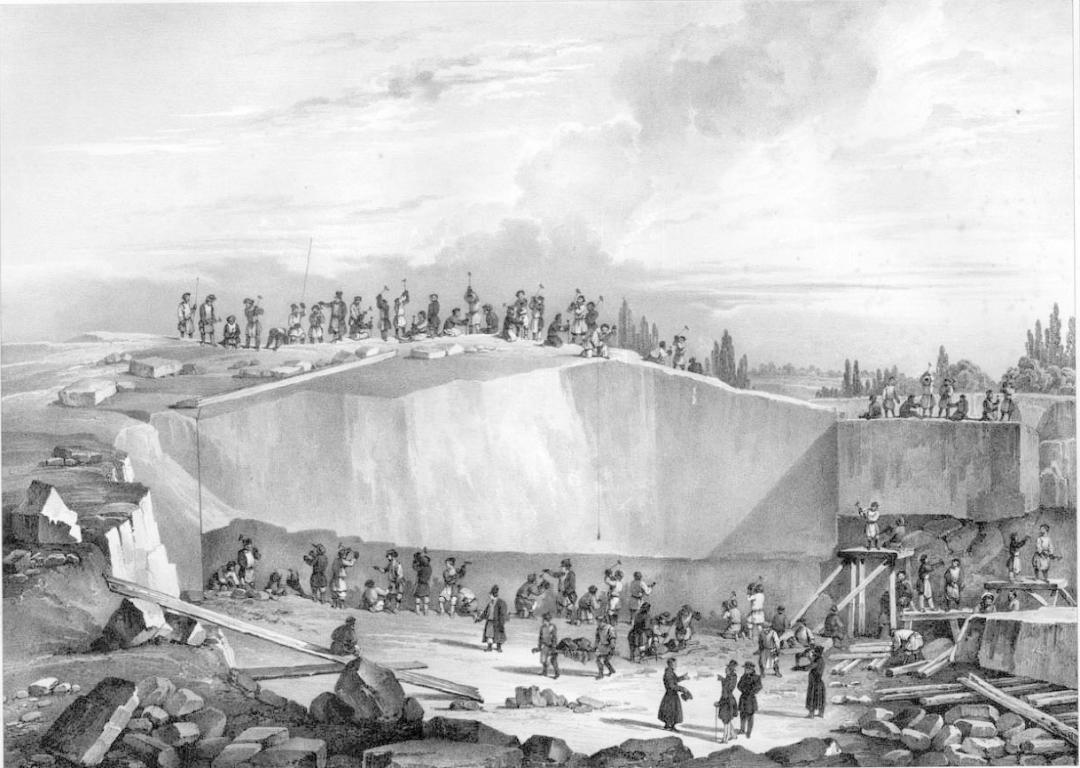

There are many theories from alternative history enthusiasts related to this monument. Fortunately, Montferrand documented the entire construction process of the tallest column in the world. Montferrand published two albums about the erection of the Alexander Column—one in color and one in black and white. The drawings detail the entire process of processing, transporting, and installing the column. They also depict the tools used to chip off the granite block of the required size. Descriptions of this process have also survived. No, the builders did not use magic or mental power to affect the rock. They worked, as expected, with special tools. Many workers were hired. Since the emperor demanded the monument be built quickly, these unfortunate workers were exploited mercilessly. Between 400 and 600 people worked per shift in the quarry.

There is a description of how exactly they created a crack in the monolithic block to chip off the needed part. For this, holes were drilled in the stone, expanded with wedges, long crowbars were inserted, and then hammered into the rock like piles. One or several people stood along the entire length of the crowbar holding it to direct it to the right spot, while other workers struck the free end with huge hammers. The noise was unbearable. But the worst off were not those who hammered but those who held the crowbar: they went deaf, lost their sight, and their muscles tore from the unbearable effort. The work was hellish and had a very high mortality rate.

After separating the block, it was trimmed to the required size, then shaped into a column. In the upper third, they began smoothly shaving off excess "shavings" so that visually the pillar appeared equal in thickness—both at the top and bottom. Special protrusions were left on the column for installation, to later secure rope rings on them.

A few words about the man historians call the creator of the Alexander Column. His name was Samson Semyonovich Sukhanov. The artel (workshop) created by this former serf clad in granite the most iconic places of Saint Petersburg, such as the Spit of Vasilievsky Island, including the columns of St. Isaac’s and Kazan Cathedrals and many monuments. "Samson Sukhanov, a peasant’s son from the Vologda Governorate, who worked in Petersburg in the first third of the 19th century, invested his labor and talent in such unique architectural creations," writes a historian. "At first, he worked alongside his brother-in-law, learning stonemasonry skills, getting used to the hammer and chisel. Once accustomed, the work went easily. Playfully, Samson turned heavy blocks, and they willingly yielded to him. It was as if he had discovered the secret: where to aim the chisel and with what force to strike."

Special technology was used for transportation—levers, winches, scaffolds, etc. The column was lowered onto a special frame equipped with runners and moved by a large group of men over other runners fitted with bronze balls (a kind of bearing) until it was brought to the ship, also specially built for its transport.

After laying the foundation, a huge 400-ton monolith was placed on it, serving as the pedestal’s base. To install the monolith on the foundation, a platform was built onto which it was rolled using rollers along an inclined plane. The stone was dumped onto a pile of sand previously laid next to the platform.

"The ground shook so strongly that eyewitnesses—passersby present on the square at that moment—felt what seemed like an underground shock."

After supports were placed under the monolith, workers shoveled out the sand and placed rollers underneath. The supports were cut away, and the block settled onto the rollers. The stone was rolled onto the foundation and precisely positioned. Ropes thrown over blocks were tightened by nine capstans and lifted the stone about one meter high. The rollers were removed, and a layer of slippery, very peculiar mortar was poured, onto which the monolith was set.

"Since the work was done in winter, I ordered the cement to be mixed with vodka and to add a tenth part of soap. Because the stone initially settled incorrectly, it had to be moved several times, which was done with only two capstans and with particular ease, of course, thanks to the soap I ordered to be added to the mortar," writes Montferrand.

During the installation of the monolithic part of the column on the pedestal, 400 builders and 2,000 veterans of the war with Napoleon—guardsmen, non-commissioned officers, sailors, and sappers—were involved. All appeared at the ceremony in full dress and with all their awards. The installation took 100 minutes, and as Auguste Montferrand himself wrote, during this time "everyone was horrified, awaiting the most terrible catastrophe." Hundreds of people watched the event, and on the day of the column’s unveiling, August 30, 1834, no fewer than 10,000 people came to Palace Square. Montferrand recalled that "the crowd soon grew so large that horses, carriages, and people blended into one. The houses were filled to the very roofs."

The 600-ton column was placed on the pedestal using a special "tower"—a drawing of this tower is in Montferrand’s album. The column was attached to the wooden structure with five rows of rope rings. It was carefully set "on its bottom" in less than two hours (as described by admiring contemporaries). The column assumed a vertical position and was held only by its own weight—no mortar was used for installation. It measured 25.6 meters in height if counting the length of the column itself, and 47.5 meters if counting the total length of all elements. It was indeed the tallest column in the world at that time—taller than Trajan’s and the Vendôme Column, which Montferrand took as a model.

However, the architect did not fully realize his plan. He dreamed of drilling the column to create a spiral staircase inside it. The French envoy at the Petersburg court, Baron de Bourgoing, who was in the Russian capital from 1828 to 1832, provides curious information about this monument: "Regarding this column, one can recall a proposal made to Emperor Nicholas by the skilled French architect Montferrand, who was present during its quarrying, transport, and installation. He proposed to the emperor to drill a spiral staircase inside this column and requested only two workers for this: a man and a boy with a hammer, chisel, and a basket in which the boy would carry out the granite debris as it was drilled; finally, two lanterns to illuminate the workers in their difficult task. In ten years, he claimed, the worker and the boy (the latter, of course, would have grown a bit) would have finished their spiral staircase; but the emperor, justly proud of this unique monument, feared, perhaps rightly, that the drilling might breach the outer sides of the column, and therefore rejected this proposal."

Exactly two years later, the entire structure was fully completed. The pedestal was clad with granite bas-reliefs, the top of the column was fitted with a bronze capital, and a brick abacus was built to install the cylindrical pedestal on which an angel with a cross was placed.

The monument is also dedicated to another great Alexander—Prince Alexander of Novgorod, known in history as Alexander Nevsky, canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church and considered the heavenly patron of Saint Petersburg. That is why both the installation of the column on the pedestal in 1832 and its unveiling in 1834 were held on September 11 (August 30 old style), the day of the transfer of the relics of Saint Alexander Nevsky to Petersburg. This is why a grand celebration took place on that day—with a solemn prayer service and parade.

To hold the troop parade on Palace Square, Montferrand’s project included the construction of the Yellow (now the Singing) Bridge.

The entire Petersburg nobility gathered for the celebration. Ordinary people could observe the epochal event from afar or from nearby roofs and trees.

Since thousands of Petersburgers saw that the colossal column was installed without any additional reinforcements and held only by its own weight, the new monument caused caution and even fear among the townspeople for quite some time—they were afraid to walk past the column, fearing it might fall due to a miscalculation by Montferrand. Countess Tolstaya forbade her coachman to drive her past the column. Probably to ease the fears of Petersburgers, Montferrand himself took long evening walks around the column with his dog until his death.

After the column’s unveiling, Petersburgers were very afraid it would fall and tried not to approach it. These fears were based both on the fact that the column was not fixed in place and on the fact that Montferrand had to make last-minute changes to the project: the blocks of the structural elements of the top—the abacus on which the angel figure was installed—were originally planned in granite; but at the last moment, they had to be replaced with brickwork bonded with lime mortar.

In the mid-1920s, when the city was renamed Leningrad, the authorities had the idea to turn the column from a royal monument into a revolutionary one. "There were very heated discussions between the chairman of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad Soviet, Georgy Zinoviev, and the head of the People’s Commissariat for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky," recalled Alexey Yerofeyev, a member of the city’s toponymic commission. "Zinoviev proposed dismantling the angel with the cross from the column and replacing it with a figure of Lenin." The gilded Ilyich was supposed to soar in the clouds, symbolizing the triumph of the proletarian revolution; however, Lunacharsky supported the defenders of the column, and the head of the Leningrad Executive Committee had to abandon his grand plan.

"Zinoviev wrote a resolution on Lunacharsky’s letter: 'To hell with them. Let them keep their column with the 'Empire angel,'" Yerofeyev recounted.

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin called the imperial column the Alexandrian Pillar. Although contemporaries suspected that the poet meant not the column but one of the wonders of the world—the Lighthouse of Alexandria in Pharos.

Sources:

http://religiopolis.org/publications/10161-tajna-aleksandrovskogo-stolpa.html