WJM5+77, 02402 Burmapınar/Kâhta/Adıyaman, Turkey

The bridge is often called the Septimius Severus Bridge — after the Roman emperor during whose reign (193–211 AD) the current structure was erected. Most likely, it replaced an earlier bridge built during the reign of Emperor Vespasian, i.e., in the years AD. Modern maps and signs often call this bridge Cendere Köprüsü, which means the bridge over the Cendere River. Older sources refer to the structure as the Chabinas Bridge. Both these names — Cendere and Chabinas — come from the river over which the building stands — the Cendere stream, a tributary of the Kâtha River (ancient Nymphaios). The name Cendere is modern, while ancient sources, including inscriptions placed on the bridge itself, mention the river Chabinas. There is also another Turkish name for this river — Bölam Su, meaning Divided Waters.

An earlier bridge over the Cendere River was built during the reign of Vespasian. However, there are no detailed records about this structure, and even the time of its construction is unknown. The attribution of this bridge to Vespasian is based on the fact that during his reign the Kingdom of Commagene was incorporated directly into the Roman Empire. Vespasian took this step because he heard rumors of a planned uprising by the last king of Commagene, Antiochus IV, against Rome. He was supposed to cooperate with the partisans. The swift intervention of Roman troops deprived Antiochus of the throne, but he lived to old age in peace and wealth, kindly provided by the Roman treasury. The loss of Commagene’s independence is recalled by the Roman historian Suetonius in "The Twelve Caesars": “[Vespasian] made Achaia, Lycia, Rhodes, Byzantium, and Samos provinces, taking away their freedom, as well as Cilicia Trachea and Commagene, which until then had been ruled by kings.”

However, the bridge dates from the reign of a much later emperor — Septimius Severus. This is confirmed by inscriptions on the bridge. Again, there are doubts about the exact date of its construction or its major repair. These arise due to contradictions in reading and interpreting these inscriptions. The inscriptions were first read and interpreted by French researchers Louis Jalabert and René Mouterde in 1929. Here is their version, published in the book "Inscriptions grecques et latines de la Syrie":

Imp(erator) Caes(ar) L(ucius) Septi/mius Severus Pius / Pertinax Aug(ustus) Ara/bic(us) Adiab(enicus) Parthic(us) / princ[e]ps felic(um) pon/tif (ex) max(imus) trib(unicia) pot(estate) / XII imp(erator) VIII co(n)s(ul) II / proco(n)s(ul) et Imp(erator) Caes(ar) / M(arcus) Aurel(ius) Antoninus/nus Aug(ustus) Augusti / n(ostri) fil(ius) proco(n)s(ul)imp(erator) III / et P(ublius) Septimius [[Ge]] /[[ta]] Caes(aris) fil(ius) et fra/ter Augg(ustorum) nn(ostrorum) / pontem chabi/nae fluvi a so/lo restituerunt / et transitum / reddiderunt / sub Alfenum Senecionem / leg(atum) Augg(ustorum) pr(o) pr(aetore) curante Ma/rio perpetuo leg(ato) Augg(ustorum) leg( ionis) / XVI F(laviae) F(irmae)

According to J. B. Lining, the main uncertainty regarding the date of the bridge’s construction arises from the difficulty in determining the years when the Roman officials mentioned in the inscriptions held their official positions. These officials were Alfenus Senecio — legate in Celesyria, i.e., the northern part of Syria and Commagene, and Marius Perpetuus — commander of the 16th Flavian Legion. The confusion is related to the imperial family titles mentioned in the same inscriptions. Lining attributed all this confusion to an error made during the preparation of the inscriptions and the mixing of imperial titles. After a more detailed analysis, he concluded that the correct date for the construction of the new bridge is 200 AD.

It seems a final answer to the question of the year the Severan Bridge was built has been given. However, the same inscriptions mention the name of the Roman legion whose soldiers worked on the bridge’s construction. This was Legio XVI Flavia Firma, created by Emperor Vespasian in 70 AD, the remnants of the XVI Gallica, which surrendered during the Batavian revolt. Legio XVI Flavia Firma was stationed on the banks of the Euphrates, in the city of Samosata, guarding the eastern border of the Roman Empire. In early 197 AD, Emperor Septimius Severus headed east to conduct a military campaign against the Parthians. The bridge over the Chabinas River was to become a strategic structure that would allow the Roman army to advance into Parthia. Returning to the previous paragraph, we learn that the date of the bridge’s construction, 200 AD, is too late because legionaries passed there three years earlier.

An alternative version of the date and reason for the bridge’s construction states that it was built not before, but after the end of the Parthian campaign. Septimius Severus defeated the Parthians, conquered and plundered their capital Ctesiphon, and incorporated the territory of northern Mesopotamia into the Roman Empire. Thus, the existing defensive line along the upper Euphrates was no longer needed. The territory was reorganized, and to facilitate communication, the bridge over the Chabinas River was erected. In this case, the year 200 is a very likely date for this event.

Now let us return to the topic of the inscriptions adorning the bridge. The above inscription and its second, almost identical version, are placed on vertical blocks embedded in the bridge’s railings. The other inscriptions, found on three columns decorating the bridge, are much shorter but add information about the contribution made by the four cities of Commagene, called “Quattuor Civitates Commag,” to the bridge.

The first of these cities is Samosata — the former capital of the Commagene kingdom and the residence of the 16th Flavian Legion. Unfortunately, the old city of Samsat was flooded by the waters of an artificial lake created by the Atatürk Dam in 1989. Another city is Perre, known in Roman times as Pordonium, an important crossroads of ancient trade routes. Its extensive ruins can be visited in the city of Adıyaman. The third city is Doliche, now a small village called Dülük, only 10 km from the center of Gaziantep. The fourth city that contributed to the foundation of the bridge was Germanicea — now known as Kahramanmaraş. Interestingly, the city began to refer to its Commagene heritage in the Roman period, but in fact, it was never part of it.

These four cities erected four columns, standing in pairs at both ends of the bridge. However, earlier in the text only three columns were mentioned, so what happened to the fourth? To explain its disappearance, we must consider the typical imperial Roman family consisting of Emperor Septimius Severus, his wife Julia Domna, and their two sons — Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus and Publius Septimius Geta Augustus. These are quite long names, but fortunately, the two brothers are better known by much shorter names, Caracalla and Geta. The brothers had already received the titles of Caesars and participated in the rule of the Roman Empire alongside their father, Caracalla from 198 and Geta from 209 AD.

Before his death in 211, Severus was to advise them: “Live in harmony, enrich the soldiers, and despise the rest of the people.” Alas, the brothers, as often happens in families, could not stand each other. Less than a year after their father’s death, the situation completely got out of control, and even Julia Domna’s attempts at mediation did not help ease the conflict. At the end of 211, Caracalla invited Geta to a meeting in their mother’s apartments, where he ordered him to be killed. Geta died in Julia Domna’s arms, stabbed by the Praetorians.

After Geta’s death, Caracalla could not stop hating his brother, so he ordered Geta’s name to be removed from all inscriptions in the empire. His monuments and portraits were also to be destroyed. Therefore, his statues are extremely rare. This practice was known in Ancient Rome as damnatio memoriae or “condemnation of memory.” One of the four columns of the Severan Bridge, dedicated to Geta, was destroyed during this procedure. Why was it not enough to erase Geta’s name? We do not know, but as a result, to this day the bridge’s appearance lacks symmetry.

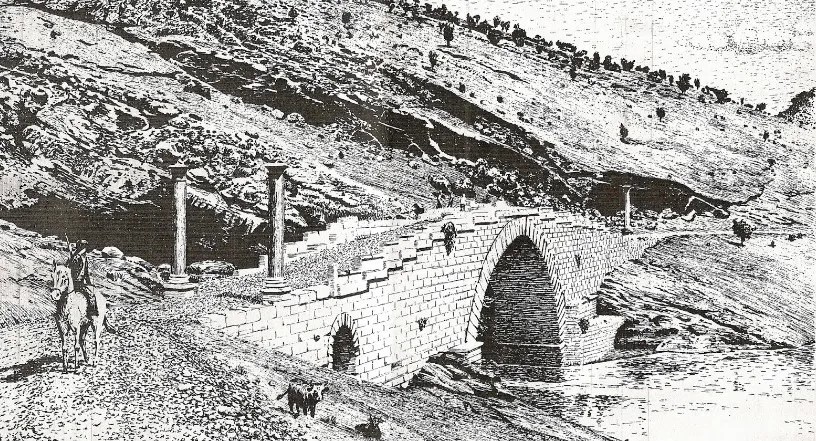

The remaining three columns are dedicated to Septimius Severus, Julia Domna, and Caracalla. The columns of the imperial couple stand on the southern side, and the column of their nervous son is at the northern end of the bridge. Originally, all columns, about 10 meters high, were topped with statues of members of the imperial family. There is a strong possibility that the columns were not originally built to decorate the bridge but were transported there from the nearby Karakush tumulus.

It is time to look more closely at the technical characteristics of the bridge. It is built as a single arch connecting the banks of the Chabinas River at its narrowest point. The total length of the bridge is 120 meters, and the width is 7 meters. The span of the arch supporting the bridge is 34.2 meters. Due to these impressive dimensions, many descriptions of the bridge state that it is the second-largest surviving arched bridge from the Roman Empire. The longest Roman arched bridge preserved to this day is the Puente Romano, which simply means Roman Bridge, over the Guadiana River in Mérida, Spain. It boasts an impressive length of 790 meters. This is a huge advantage over the 120-meter Septimius Severus Bridge. At the same time, given such a large difference in size between these bridges, one can assume that other Roman bridges exist that would rank between them. Even a cursory glance at lists of existing Roman bridges shows that Taşköprü — the Stone Bridge — in Adana is 310 meters long, Trajan’s Bridge in Alcántara, Spain — 182 meters, and the segmental arch bridge in Limyra, Turkey — 360 meters.

Finally, a few facts from the recent history of the Septimius Severus Bridge. The first description and illustrations of this structure were provided by Osman Hamdi Bey and Osgan Efendi in 1883. In the 20th century, the bridge underwent reconstruction twice — in 1951 and 1997. After these repairs, access to the bridge was gradually restricted. Finally, after the construction of a new bridge, the Roman bridge was completely closed except for pedestrian traffic.

Sources:

https://turkisharchaeonews.net/object/severan-cendere-bridge